Received 11 August 2022; Revised 3 October 2022; Accepted 20 October 2022.

This is an open access paper under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

Francesca Bartolacci, PhD., Associate Professor, Department of Economics and Law, University of Macerata, Via Crescimbeni, 30/32, 62100 Macerata, Italy, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Andrea Cardoni, PhD., Associate Professor, Department of Economics, University of Perugia, Piazza Universita, 1, 06123 Perugia, Italy, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Piotr Łasak, PhD. Hab., Associate Professor, Institute of Economics, Finance and Management, Jagiellonian University, ul. Prof. S. Łojasiewicza 4, 30-348 Kraków, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Wojciech Sadkowski, PhD., Associate Professor, Institute of Economics, Finance and Management, Jagiellonian University, ul. Prof. S. Łojasiewicza 4, 30-348 Kraków, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Abstract

PURPOSE: The paper aims to identify the characteristics of the entities involved, the motivations and the processes of forming strategic alliances between a small cooperative bank and a fintech start-up. The paper bridges the research gap in the literature and explains the success factors of strategic alliance between considered entities. METHODOLOGY: We applied a typical qualitative research approach that consists of two steps. The first step was to develop an analytical framework to understand the critical success factors for the strategic alliance formation between banks and fintech start-ups. In the second step, we applied the analytical framework for a case study analysis, considering the strategic alliance between the Banca Popolare di Cortona and the NetFintech start-up. FINDINGS: Our research shows that there are different motives for strategic alliance formation for banks and fintech start-ups. From a theoretical point of view, banks’ motivations are based on outsourcing, innovation, the evolution of the business model, competitive advantage, saving costs, improving service quality, and learning. The main motives for fintechs include access to customers, loans, banking license, economies of scale, trust, and credibility. In the empirical part, we found that the crucial success factors are strategic alignment and hybridization, competence and experience, cultural value and territorial closeness, and professionalism. IMPLICATIONS: The results develop the knowledge about the best conditions for cooperative banks and fintech start-ups strategic alliances. The main limitation is that the paper is based only on one case study and it is related to cooperative banks and does not embrace other groups of banks. For this reason, it can be a basis for further research in this area. The described case study can be a good example to compare other cases of such alliances. Cooperative banks and fintech start-ups involved in a strategic alliance should share the commitment at the governance level. Critical are also the procedures of the alliance formation. ORIGINALITY AND VALUE: This article provides two main contributions to the literature on the technology-driven transformations of the banking sector. First, we elaborated a theoretical framework of the critical success factors for the bank and fintech start-up strategic alliance formation. Second, we applied the framework with the bank–fintech start-up cooperation in the local market in Italy. Contrary to previous research, which focuses mainly on commercial banks, this article presents the relationship between cooperative banks and fintech start-ups.

Keywords: incumbent bank, cooperative bank, fintech start-up, strategic alliance, success factors

INTRODUCTION

The integration between banks and fintech start-ups belongs to an important topic in the financial ecosystem innovation and development (Zachariadis & Ozcan, 2017). The latest innovative processes show that we are in a time of profound digital transformation in banking. The traditional model of hierarchical dominance of banks has ceased to prevail in finance activity. The existing hierarchical structure is being replaced by heterarchical networks of banks and non-banking entities (Chiu, 2017; Nicoletti, Nicoletti & Weis, 2017). During such transformations, various hybrid forms (arm’s length transactions) are more common and innovative ecosystems are created, such as digital platforms (Pedersen, 2020; Sironi, 2021). In this context, the strategic alliances between banks and fintech start-ups represent a pivotal partnership to realize competitive business activities.

In this article, an incumbent bank is recognized as a regulated financial institution that focuses on accepting deposits and making loans. We distinguish incumbent banks, a general category of banks, from cooperative banks, a special group that have particular importance in some countries (Angelini, Di Salvo & Ferri, 1998). Moreover, when referring to incumbent banks, we consider traditional institutions that normally do not apply digital solutions (main determinants of challenger banks and neobanks creation). Following the literature, a fintech start-up is defined here as non-bank institution that uses technology to provide a financial service (Łasak & Gancarczyk, 2021; Zavolokina, Dolata, & Schwabe, 2017).

Banks and fintech start-ups try to overcome the difficulties they encounter by operating as single entities and seek to gain competitive advantage through long-term cooperation. Among these, one of the most frequently made management decisions is the strategic alliance (Inkpen & Tsang, 2016), which has influenced the development of scientific research over time (Gomes, Barnes & Mahmood, 2016). A significant body of literature focuses attention on strategic alliances as an essential source of critical knowledge and other important resources to gain and maintain a competitive advantage (Davies, 2009; He, Ghobadian & Gallear, 2021). Although many studies analyse this kind of collaboration, there is a lack of empirical studies that examine the determinant factors of strategic alliance success (Taylor, 2005; Varadarajan & Cunningham, 1995; Wittmann, Hunt, & Arnett, 2009) with particular attention to the formation phase, especially when a bank and a fintech start-up are involved.

Our paper is an attempt to bridge this literature gap and provides a study of strategic alliance formation between an incumbent traditional bank and a fintech start-up. We highlight the difficulty in building a successful strategic alliance and this paper aims to develop a conceptual framework for the creation of such cooperation. The problems that usually arise when realizing effective strategic alliances motivated us to research the factors that determine their success. For this purpose, we formulated a research framework, which embraces the three most essential pillars: the motivations for the alliance, the characteristics of involved entities, and the crucial requirements for alliance formation. The framework is applied with a single case study through an in-depth analysis of the strategic alliance between the two Italian entities, Banca Popolare di Cortona and the fintech start-up NetFintech. The Banca Popolare di Cortona is a cooperative bank from Cortona (Toscana, Italy) whereas the NetFintech is a local fintech start-up from Arezzo (Toscana, Italy).

This paper provides two contributions to the literature on technology-driven transformations of the banking sector. First, we elaborate a theoretical framework which enables us to identify the critical success factors of banks and fintech start-ups’ strategic alliance creation. Second, we applied our model with the local businesses in the Italian banking sector. Although, many examples of cooperation between commercial banks and fintech start-ups are in the literature, there is still a lack of research on the impact of financial technology on cooperative banks, especially strategic alliances between those banks and fintech start-ups.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 describes the literature review on the relations between incumbent banks and fintech start-ups. We then provide the methodology in section 3. In section 4, we present the framework adapted to analyse the dynamic of integration and support it with the practical example of the alliance in section 5. Section 6 discusses the success factors that made the model promising and efficient. And in the last section, the conclusions and suggestions for future research are provided.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Cooperative banks and fintech start-ups

Traditional banks are institutions with a long tradition in offering banking services and they can be divided into a few groups. Apart from commercial banks and saving banks, we can distinguish cooperative banks. The main difference is that cooperative banks are owned and operated by the members for a common purpose. Their main goal is to generate value mainly for stakeholders instead of exclusively for shareholders. Cooperative banks belong to small institutions, and they usually service agriculture and small business (Angelini et al, 1998; Meyer, 2018; Migliorelli, 2018). Such principles as cooperation, democratic decision making and mutual help by the members play a significant role in this group of financial institutions. These banks play an important role in some European countries, like France, Germany, Italy, and Spain (Bülbül, Schmidt & Schüwer, 2013; Hesse & Heiko, 2007).

The term “fintech start-up” is strictly connected with the term “fintech”. Fintech comes from financial technology and is understood in two ways, firstly, digital technologies and related innovations focused on financial services, secondly, the term relates to fintech-based businesses (Gomber, Koch & Siering, 2017; Puschmann, 2017). Such businesses rely on innovative solutions to improve financial performance (Tanda & Schena, 2019). To achieve this goal they use different solutions, namely, software, applications, products, processes, and services. Usually they focus on particular areas of financial services, e.g. payments (Nicoletti, 2021). Among such entities are different groups of companies, for instance, big companies having their main operations in different industries. There are also newly created entities which are called fintech start-ups (Benziane, Roqiya & Houcine, 2022; Haddad & Hornuf, 2019). Such entities exert great impact on the current business models of incumbent banks (Łasak & Gancarczyk, 2022). We separate fintech start-ups, which originally do not belong to the banking sector, from challenger banks and neobanks, whose activity is based on new technologies, but they have a banking licence and belong to the banking sector. We consider only the non-bank entities as fintech start-ups.

The impact of fintechs on incumbent banks

The last decade is defined by the rapid development of financial technologies and their entrance into the banking sector. At the beginning, traditional banks and institutional investors monopolised financial innovations based on new technology. Since the global financial crisis of 2008, the situation changed and new actors entered into traditional financial sectors. The literature highlights the positive influence of fintechs on traditional banking sectors. In the first phase of bank–fintech relations, there was an influence of financial technologies on banking activity. Among the most important aspects related to the issue include 1) an increase in the scale of the operations, 2) the introduction of new (more efficient) services, and 3) an increase in the number of customers (Campbell-Verduyn, Goguen & Porter, 2017; Gomber et al., 2017; Iman, 2018). A significant consequence of the cooperation between banks and fintech start-ups is created for developing countries, where society’s access to traditional banking is limited. The relationship between banks and non-banking fintech entities enables access to banking services for those who were excluded before (Demir, Pesqué-Cela, Altunbaş & Murinde, 2020; Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, Singer, Ansar & Hess, 2020; Jagtiani & Lemieux, 2018).

Despite improving the banking services offered through financial technologies, the negative impact of non-banking entities on traditional banks is sometimes indicated. Some researchers even argue that the entrance of non-bank competitors and technology-driven entities have a disruptive effect on traditional banking (Coetzee, 2018; Hodson, 2021). The technology leads to the profound disintegration of the bank business model (Boot, Hoffmann, Laeven & Ratnovski, 2021). The influence of financial technologies on banks is particularly evident in banks’ front offices, responsible for customer services (lending, payment, and wealth management). However, they are equally common in banks’ middle and back office operations (Łasak & Gancarczyk, 2022). Boot et al. (2021) highlight that offering specialised financial services does not require a full banking licence. We observe a transformation from a bank-centred approach to a customer-centred approach in the banking industry (Chen, Li, Wu & Luo, 2017). As a consequence, a less bank-centric financial industry structure emerges. We also observe a change from traditional, bricks-and-mortar branches to virtual, online-based banking services (Coetzee, 2018). All these changes cause banks to have to offer a new dimension to their services. The need leads to a search for a new business path and opens the process of alliances between banks and fintech start-ups (Son & Kim, 2018).

The literature related to the impact of fintechs on incumbent banks is mainly associated with commercial banks. Relatively rarely is the influence of fintechs on cooperative banks analysed. Meantime, cooperative banks have become more and more important nowadays. They provide credit to households and small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Migliorelli (2018) emphasizes that the entrance of fintechs into the banking sector creates a new situation for cooperative banks. They should be able to bridge the gap with new entrants and seize the opportunity before the market moves into a new, advanced growth stage. It is important to be aware that sometimes the impact of fintechs on cooperative banks is stronger than the impact on commercial banks. Flögel & Beckamp (2020) point out that, nowadays, strong competition is observed within the digital provision of bank services, and the competition is especially difficult for small branches. The way of customer servicing has changed, and the new, digital solutions create more attractive customer interfaces than traditional banks. Moreover, digitalization offers strong economies of scale, which undermines the efficiency of smaller entities (Meyer, 2018). In such circumstances, cooperative banks respond by offering digital channels of distribution of their services. It also opens the possibility for cooperation between cooperative banks and fintech start-ups.

The impact of fintechs on banks also has a spatial dimension. Firstly, financial technology stimulates the transition from bank internal governance to network and market governance (Brown & Piroska, 2021; Langley, 2016). It has an important impact on cooperation between banks and fintech start-ups and, among others, strategic alliance creation (Clarke, 2019). Secondly, the bank and non-bank cooperation stimulates development of financial ecosystems where retail banks and place-based projects become more significant (Appleyard, 2020; DawnBurton, 2020; Lai, 2020). They have not only a global, but especially a regional and local dimension. Such development creates great opportunities for cooperation between cooperative banks and fintech start-ups, which usually is stronger in a local dimension as a consequence of the nature of cooperative banking.

The role of strategic alliance in banking

An alliance is defined as a long-term collaborative relationship between two or more independent firms (Hamel & Prahalad, 1990; McCarthy & Aalbers, 2022; Teece, 1992) in which they combine resources in an effort to achieve mutually compatible benefits that they could not easily obtain alone (Franco, 2011; Nguyen & Tran, 2017). A strategic alliance is a voluntary arrangement among firms that involves the exchange, sharing, or co-development of products, technologies, and services (Gulati, 1998). Also Eckman and Lundgren (2020) argue that the core motivation of strategic alliances is the opportunity to access new resources and the willingness to develop innovation, with the aim to identify new products or new industry standards. A synergetic interplay, based on the exchange of technology and know-how (Fang, Francis, Hasan & Wang, 2012), may allow alliances to achieve collective commercial goals (Todeva & Knoke, 2005). For Lawrence, Hardy and Phillips (2002), strategic alliances are often a way to develop new solutions to complex problems when facing an increasingly difficult competitive arena (Gomes-Casseres, 1996). Given their importance, strategic alliances recently increased in popularity (He et al., 2021), quickly becoming a major strategic tool that few firms can afford to ignore (Rindfleisch, 2000).

The managerial literature discusses in detail the role and motivations of strategic alliances. Companies use this form of collaboration to achieve organizational flexibility, economies of scale, cost reductions, market entry, exports, competitiveness, and improve diversification through new product development (Abdollahbeigi & Salehi, 2021). Other authors indicate company growth, new technology, better quality, greater investments’ efficiency, reduction of financial risk, cost sharing (Deeds & Hill, 1996; Kotabe & Swan, 1995; McCarthy & Aalbers, 2022), new markets and competitive advantages (Elmuti & Kathawala, 2001; Lütolf-Carroll & Pirnes, 2009; Zamir, Sahar & Zafar, 2014; Hussein, 2021).

Traditional banks usually had a hierarchical structure given the particularity of banking activity strictly regulated by law. The liberalization of this activity and the appearance of new fintech start-ups into the sector determined the flattening of this structure and, over time, the creation of new ecosystems (Omarini, 2018). In this context, strategic alliances are crucial forms of cooperation between banks and fintech start-ups (Drasch, Schweizer & Urbach, 2018; Oshodin, Molla, Karanasios & Ong, 2017) that have increased digitization of banking services and created added value for customers (Fonseca & Meneses, 2020). The digitalization processes and the most recent competitive dynamics have generated changes in the banking structure according to a hybridization approach (Drasch et al., 2018; Schwab & Guibaud, 2016; Zachariadis & Ozcan, 2017). Strategic alliances between banks and fintech companies are oriented toward distributing financial products and services via digital channels (Scardovi, 2017; Tanda & Schena, 2019). They appear to be hybrid structures aimed at leveraging firms’ resources and enhancing their competitiveness while maintaining their independence (Akpotu, 2016; Holotiuk, Klus, Lohwasser & Moormann, 2018). The involved banks and fintech start-ups can achieve the best results from cooperation in an environment of newly created digital ecosystems (Carbó-Valverde, Cuadros-Solas & Rodríguez-Fernández, 2021). The ecosystem is understood as the alignment structure of a multilateral set of partners who must interact for a value proposition to materialize their goals (Adner, 2017; Svensson, Udesen & Webb, 2019).

Crucial aspects to achieve the expected performance are the planning process of the collaboration (Arslan, Archetti, Jabali, Laporte & Speranza, 2020) and the selection of an appropriate partner (Amin & Boamah, 2022) with whom to create an alliance based on mutual trust and the sharing of critical information and resources (Lütolf-Carroll & Pirnes, 2009). It is, however, highlighted that it is tough to build a successful alliance and, therefore, fundamental there is proper formation and management of the main aspects of the strategic alliance (Russo & Cesarani, 2017). The critical issue is how the partners participate in the formation of the alliance and how they manage the interdependence that exists between them (Das & Kumar, 2011).

Though the strategic alliances formed are growing, because of problems such as instability and poor negotiation, these alliances may be more expensive and difficult and less efficient to manage than expected if not adequately planned (Contractor & Lorange, 2002; Jiang, 2011; Minshall, 1999). The evidence that more financial institutions are forming strategic alliances suggests the need to identify the main elements of a theoretical framework of these specific alliances’ formation, which can aid their effective implementation and avoid inefficiency, conflict and instability over time.

The critical success factors of strategic alliance

The development of the research framework of a cooperative bank and fintech start-up strategic alliance formation, allowed us to identify the critical success factors for such an alliance. The following subsections highlight the critical success factors of a strategic alliance between banks and fintech startups.

Strategic alignment and hybridization

Today the dominant view in the literature is that cooperation between traditional banks and fintech start-ups is a much better solution than the competition (Elia, Stefanelli & Ferilli, 2022). In this way, each of these entities can get better results than if they were operating independently (Anand & Mantrala, 2019). As clarified in the previous parts of the paper, strategic alliances are one of these forms of cooperation between incumbent banks and fintech start-ups, which is beneficial for both parties (Hornuf, Klus, Lohwasser & Schwienbacher, 2021). This argumentation is one of the crucial drivers of strategic alliance creation. The benefits of the collaboration of banks with fintechs are ample. Banks have a customer base and infrastructure, while fintechs excel in technology and innovation (Kyari, Waziri & Gulani, 2021). Fintechs’ motivations also focus on banks’ funds, networks, and reputation. The strong motivating factor for banks is cost savings, while fintechs’ motivations also concentrate on banks’ funds, networks, and reputation (Bömer & Maxin, 2018). Svensson et al. (2019) highlight the legitimating functions of alliances. Incumbent banks and fintech start-ups can enhance their organizational legitimacy through the joint accomplishments arising from alliances. The minority share investments are more popular than other forms of alliances and enable banks to internalize the knowledge of a fintech and obtain sole possession of its understanding. This kind of investment incorporates a relatively low level of hierarchical control of the cooperation by one of the alliance’s partners. The crucial determinant of cooperation is the ability of the partners to coordinate activities across themselves. It embraces such activities as collecting and disseminating information, making decisions, resolving potential conflicts, and guiding interdependent actions. In this type of partnership, the participating entities work together without creating a new entity (Gulati & Singh, 1998).

Competence and experience in the real market and SME’s financial needs

One of the crucial aspects of successful banking activity is the understanding of the needs of customers. This is more important while banking services are becoming digitized. Anand & Mantrala (2019) point out that sometimes banks lack the competence to understand millennial customers, while fintech start-ups can better understand their needs. The same opinion is presented by Nicoletti et al. (2017), who also argue that customer centricity and applying financial technologies in banking activity can enhance the customer experience. Omarini (2018) highlights the significance of synergies generated by complementary core competences and experiences possessed by banks and fintech start-ups. A significant level of competence and experience is needed especially in such markets where the services are offered to those customers who were financially excluded (Glavee-Geo, Shaikh, Karjaluoto & Hinson, 2019).

Customer needs definitely impact the success of strategic alliance when banking services become customer-centric (Acar & Çıtak, 2019; Nicoletti et al., 2017). Both banks and fintech start-ups have some advantages in this field. While banks have customer bases and loyalty, fintech start-ups have the agility to adjust to new customer needs. It is a fact that customer loyalty is a crucial aspect of the relations between banks and their customers but, nowadays, customers’ demands are changing from static and predictable to dynamic and unpredictable (Schmidt, Drews & Schirmer, 2017). In an era of digitalization, innovativeness and quality of services are the main drivers of customer satisfaction in banking services (Hornuf et al., 2021), and this exerts tremendous pressure for a change in banks’ business models. Banks try to address specific customer needs, and the collaboration with fintechs enables them to improve their customer-centric orientation. Fintechs are usually quicker and more agile in providing digital services for customers. In addition, fintechs provide solutions to improve the banks’ potential for digital technologies, which is why they attract new customers (Böttcher, Al Attrach, Bauer, Weking, Böhm & Krcmar, 2021). In the literature, attention is paid to the limited access of SMEs to financing via traditional channels (Vasilescu, 2014). For this reason, fintechs have become a significant source of SME financing (Cichy & Gradoń, 2016; Eldridge, Nisar & Torchia, 2021; Fasano & Cappa, 2022; Ferreira, Eça, Prado & Rizzo, 2022). Temelkov (2018) points out that the alliance between banks and fintech start-ups can be beneficial for SMEs in this area. It is especially significant in such countries where small businesses have limited access to traditional banking (Babajide, Oluwaseye, Adedoyin Isola Lawal & Isibor, 2020; Xiang, Zhang & Worthington, 2018).

Cultural value and territorial closeness to create trust and commitment at the top governance level

Apart from managerial and organizational skills, the cultural similarity or differences between alliance partners also play an important role for the success of joint cooperation. Those partners who are responsible for forming a plan of strategic alliance should be willing to compromise, when it is necessary, for their joint collaboration (Albers, Wohlgezogen & Zajac, 2016; Russo & Cesarani, 2017). Empirical research confirms that cultural consistencies and local character of cooperation (physical proximity) are important factors for building relationships between banks and fintech start-ups (Hommel & Bican, 2020). Local conditions play a significant role in the relationship between these partners and impact their cooperation in a two-dimensional way. The first dimension gives an advantage to banks as they are naturally related to the local market, have close relationships with their customers, and at the same time have extensive knowledge of this market. New entrants very rarely have such advantages. The second dimension is related to technological advancements and innovativeness. It is highlighted in the literature that some incumbent entities are characterized by a lack of in-house talent and innovative culture. Local banks sometimes operate on traditional methods and do not have the ability to modify their approach to the extent required by the dynamically developing financial technology. The cooperation between incumbent institutions and new entrants (fintech start-ups) reduces this disadvantage (Murinde, Rizopoulos & Zachariadis, 2022).

The literature indicates that the creation of successful alliances is based on the strong commitment and trust of the participants. Such relational factors, like mutual trust and mutual commitment, are treated as a form of relational safeguard (Russo & Cesarani, 2017). While Albers et al. (2016) pay attention to the role of trust in strategic alliance creation, Teng and Das (2008) argue that trust and mechanisms of governance are strictly interrelated. They indicate that such types of risk, like relational and performance risk, influence both governance mechanisms and bilateral trust between strategic alliance partners. Trust plays an important role in explaining the coopetition relations between banks and fintech start-ups and in the success of their alliance (Eckman & Lundgren, 2020).

Professionalism in strategic assessment and contractual agreements

Proper management is important for a successful strategic alliance. Drasch et al. (2018) highlight that a strategic alliance has a greater possibility of success if the involved parties’ managers are well prepared to manage alliances, have previous knowledge, and are dedicated to this form of cooperation. Managers, who understand the processes of digitalization, may significantly contribute to the success of such an alliance. Hornuf et al. (2021) make a hypothesis that banks with a chief digital officer (CDO), or with digitalization defined as an important goal of their corporate strategy, are more likely to establish alliances with fintechs. It suggests that banks with a clear digital strategy are more likely to have alliances with fintech start-ups than banks without such a strategy. Hommel and Bican (2020) emphasize the role that the relevant market experience of founders, a clear vision and a strategy, has on running an alliance successfully.

Our research process enables greater understanding of the strategic alliances between cooperative banks and fintech start-ups. More precisely, we believe that it is useful to understand:

- how banks and fintechs must deal with the formation of strategic alliances in the light of their characteristics;

- what are the main motivations and objectives pursued by these financial operators;

- whether it is possible to identify some critical factors for the success of the alliance between Banca Popolare di Cortona (BPC) and NetFintech (NF) start-up.

The answer to these questions, as well as providing a discussion in the context of the ongoing literature on the bank–fintech start-up cooperation, is our main contribution.

METHODOLOGY AND DATA COLLECTION

In our study, we applied a typical research approach that is used in qualitative research and we followed a two steps approach. The first step was to develop an analytical framework, which enables an understanding of the critical success factors for the strategic alliance formation between cooperative banks and fintech start-ups. The framework has been elaborated by considering the literature that analyses the impact of financial technologies on the operation of banks and the importance of strategic alliances in the context of the relations between cooperative banks and fintech start-ups. Particularly, we adopted a review of the literature including scientific articles, organization reports, and press releases. We used the large and recognized databases Scopus and Web of Science that cover the leading journals and book series in science. The search was limited to social sciences and related sciences, and the time period 2010-2022. We searched according to the keywords “bank*” and “fintech*”. This search enabled the study of the nature of cooperation between banks and fintech start-ups. We found 988 documents related to the keywords. After the initial examination of the titles, keywords, and abstracts, we selected 121 papers for more detailed study. We focused on the parts related to the bank–fintech start-up cooperation. In the next step, we included the keyword “alliance” to our search. This search enabled us to find 11 documents on the basis of which we tried to identify the mechanisms of alliance formation. The third approach was a combination of the keywords “bank*” and “strategic alliance”. Another group of 124 documents were selected. In the next stage, we reviewed the selected articles and coded the information manually, focusing on such keywords like “bank*”, “cooperative bank*”, “fintech start-up*”, “alliance formation”. In such an approach we obtained the necessary information and discussed them in the context of our research, eventually achieving consensus on the main constructs of the theoretical framework of our research. On the basis of the literature study, we firstly considered of the impact of fintech start-ups on banking activity and bank business models. After the initial consideration, we narrowed our research to strategic alliance formation between banks and fintechs. We focused on three crucial areas defining our framework, namely, 1) identification of the characteristics of the involved entities, 2) defining the motivations for the alliance, 3) identification of the process of the alliance formation.

In the second step of the research process, we applied the analytical framework for a case study analysis, considering the strategic alliance between an Italian incumbent bank and a fintech start-up. This step enables the contextualization of our previous steps with the aim to employ the analytical framework and identify the critical success factors for an alliance between a small cooperative bank and a fintech start-up. The application of the case study corresponds to the patterns described in the literature, including Baxter and Jack (2008), Dul and Hak (2007), Eisenhardt (1989), Harrison, Birks, Franklin and Mills (2017), Merriam and Tisdell (2015), and Stake (1995). In line with the assumptions for the application of the case study (Budzanowska-Drzewiecka, 2022; Yin, 2015), our goal was to focus on our analytical framework. We selected this case because the Italian banking sector belongs to the biggest banking sectors in the European Union. There is a large number of banks, the concentration of the sector is relatively low, and the five largest banks pose around 40% of the whole sectors’ assets (Bilotta, 2017). Moreover, the Italian banks are relatively small, considering the value of assets or the number of employees. They are either limited companies, cooperative banks (Banche Popolari), or mutual banks (Banche di Credito Cooperativo) (De Bonis, Pozzolo & Stacchini, 2011). The cooperative banks in Italy have relatively modest market share when compared with cooperative banks in other European countries. In 2017 they were responsible for between 7-8 percent of total customer loans and customer deposits (Poli, 2019). Despite the fact that these banks are responsible for relatively small part of the Italian banking sector, two things are significant – the cooperative banks are important in Italian banking history, and they are able to meet the needs of those customers who might otherwise be excluded from accessing financial products and services (Jensen, Patmore & Tortia, 2015).

To employ the framework, we selected the case of the strategic alliance between Banca Popolare di Cortona (BPC) and NetFintech (NF) start-up. BPC is a traditional local bank, founded in Cortona in the province of Arezzo in 1881, and has the legal form of limited cooperative company. BPC is the oldest, small-sized popular bank operating in Italy which, inspired by the principles of popular credit, currently serves the communities residing in the area included between the provinces of Perugia and Arezzo, and in particular those of the Valdichiana (De Lucia Lumeno, 2011). NF is a limited liability company registered in Arezzo that operates in the development, production and marketing of innovative products and services with high technological value in sectors such as credit mediation.

This alliance has been selected as a relevant case for the following reasons. First, we found that the entities involved represent the typical actors that are now facing the challenge of promoting a strategic alliance, emphasising the need for integration between a traditional and innovative approach in the financial ecosystem. Second, since BPC is a local bank operating in a cooperative logic, we found that this case is under investigated in the scientific literature, especially with reference to financial innovation and technology. Indeed, these subjects are usually reserved for big banks allying with fintech start-up in the financial eco-system of the most innovative financial regions and centres. Also, with regard to the fintech start-up, the case considers a reality that has developed in a traditional economic–productive district, characterized by a strong presence of SMEs and a certain distance from advanced financial districts. For these reasons, it is believed that the chosen case is adequate to prove the framework, given its high level of innovativeness and originality, filling a gap in the literature.

The case of the strategic alliance between BPC and NF was analysed using different data sources, which were used for triangulation and external and internal validation of the information (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Dul & Hak, 2007; Eisenhardt, 1989; Harrison et al., 2017; Merriam & Tisdell, 2015; Stake, 1995). In particular, we have collected information through the following sources (Table 1):

Table 1. Data sources

|

Details |

Organization (Role) |

Contents |

Date |

Reference |

|

Conference material |

||||

|

Ivan Pellegrini |

Italia Fintech (Director) |

Introduction to the event |

17 September 2021 |

CM1 |

|

Laura Grassi |

Fintech Observatory – Politecnico di Milano (Professor) |

The collaboration between incumbent banks and fintech start-ups |

17 September 2021 |

CM2 |

|

Tiziano Cetarini |

Agile Laboratory Ecosystem (CEO) |

Change Capital development in the Agile Laboratory Ecosystem |

17 September 2021 |

CM3 |

|

Roberto Calzini |

Banca Popolare di Cortona (General Manager) |

The strategic objectives of strategic alliance with Change Capital |

17 September 2021 |

CM4 |

|

Francesco Brami |

NetFintech - Change Capital (CEO) |

Change Capital business model and strategic plan |

17 September 2021 |

CM5 |

|

Semi-structured interviews |

||||

|

Roberto Calzini |

Banca Popolare di Cortona (General Manager) |

The framework for strategic alliance formation: Banca Popolare perspective |

July 2022 |

IS1 |

|

Francesco Brami |

NetFintech - Change Capital (CEO) |

The framework for strategic alliance formation: NetFintech perspective |

July 2022 |

IS2 |

|

Internal documents |

||||

|

Financial Statement as at 31st Dec 2021 |

Banca Popolare di Cortona |

- |

May 2022 |

ID1 |

|

Financial Statement as at 31st Dec 2021 |

NetFintech - Change Capital |

- |

May 2022 |

ID2 |

|

Business Plan |

NetFintech - Change Capital |

- |

May 2021 |

ID3 |

|

Advisor analysis and assessment |

KPMG |

- |

April-May 2021 |

ID4 |

|

Contractual Agreement |

Banca Popolare di Cortona-NetFintech |

July 2021 |

ID5 |

|

RESULTS

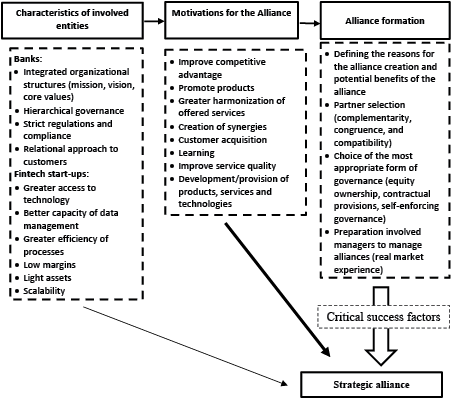

An analytical framework for strategic alliance formation between cooperative banks and fintech start-ups

The problems that usually arise when creating effective strategic alliances motivated us to identify the factors determining the creation of successful strategic alliances in the banking sector, addressing the question in the specific context of the process of strategic alliance creation between cooperative banks and fintech start-ups. For this purpose, we formulated our research framework, which embraces the three most essential pillars: defining the motivations for the alliance, providing characteristics of involved entities, and expressing the crucial requirements for alliance formation (Figure 1). The research framework should answer the question of the critical success factors for strategic alliance creation in bank–fintech cooperation. The detailed description of the three pillars, which constitute our theoretical research framework, is based on desk research. The motivations for the alliance explain why banks cooperate with fintechs in such a form of cooperation. The characteristics of involved entities provide a more detailed description of the banks and fintechs’ features. The alliance formation describes the first stage of the “alliance lifecycle”, defined by Russo and Cesarani (2017). In our research framework, we have omitted the next steps that embrace the “alliance operational phase” and “alliance evaluation”.

Characteristics of involved entities

Banks play a unique role in economies as they are financial intermediaries between savers, investors, and institutions responsible for money creation (Bertocco, 2004; Schooner & Taylor, 2009). They are strictly regulated institutions which create their special status and constitute a barrier to the entrance of other, non-bank entities into the sector (Carletti & Hartmann, 2003; Murinde et al., 2022). Many banks have long-term relationships with their customers, creating a unique environment for closer cooperation and giving a natural advantage over other entities (Jakšič & Marinč, 2019). However, the existing advantages of banks are gradually losing their importance. Greater digitalization of the processes and activities in the banking industry means that, nowadays, banks cannot rely only on their internal competencies. They must complement their competencies with those provided by other non-bank companies if they want to stay in the market (Schmidt, Drews & Schirmer, 2018).

Figure 1. The research framework of the cooperative bank

and fintech start-up strategic alliance formation

Fintech start-ups have different characteristics. Greater access to new technologies and the use of new technologies gives their customers greater availability than traditional banks (Bhagat & Roderick, 2020). They have advantages over banks because they can accomplish many activities faster and achieve greater economies of scale and scope. Fintechs can enhance the speed, transparency, access and security of services (Murinde et al., 2022). They also offer the possibility of faster and more convenient data processing, which can optimize and innovate banking services (Schmidt et al., 2018). Among other features of fintechs are low-profit margins, light assets, scalability, greater innovativeness, and lower regulatory restrictions (Bömer & Maxin, 2018; Lee & Teo, 2015). The low profit margins stem from more significant economies of scale and an appropriate costs structure (low share of fixed costs). There are also advantages coming from greater scalability of the business (fintechs can increase the scale of their activity without drastically increasing in costs).

The successes of fintechs in offering banking services are not only from the use of technology per se. There are also some other critical aspects contributing to the growing role of fintechs. Among the most important are enumerated: delivered product (service), customer base, management and high organizational culture, and also the possibility of cooperation with other entities (Karmańska, 2021).

Motivations for the bank–fintech start-up alliance

The contemporary financial ecosystems are different from structures that operated in the past. They consist of the entire range of market players together with their processes, products and new entities entering the financial market and the transmitters enabling contact with their customers. There are also many supporting actors, like data providers, exchanges and regulatory agencies (Bose, Dong & Simpson, 2019). Moreover, the current financial ecosystems are subjects of dynamic changes (Hacioglu & Aksoy, 2021; Somin, Altshuler, Gordon, Pentland & Shmuel, 2020). The digitalization of banking services triggers the creation of such digital ecosystems where incumbent banks and fintech start-ups work closely together (Dapp, Slomka & Hoffmann, 2015; Liu, Kauffman & Ma, 2015). Financial ecosystems development is the crucial dimension of coupling between traditional banks and fintech companies (Arslanian & Fischer, 2019; Hendrikse, Van Meeteren & Bassens, 2020). In such an environment, banks and fintechs have many motivations to build strategic alliances (Drasch et al., 2018).

Among the most popular forms of cooperation are VC or direct investment, collaboration via platforms, in-house development of products based on fintech solutions, or M&As (Gharrawi, 2018; Murinde et al., 2022). Strategic alliances belong to the crucial forms of responses of the traditional institutions as a reaction to the entrants with disruptive business models (Anand & Mantrala, 2019).

The reasons why banks cooperate with fintechs and form alliances can be considered from numerous points of view. Banks fail to serve today’s digital savvy customers (Eckman & Lundgren, 2020) and they can improve their value through the implementation of financial innovations. Hornuff et al. (2021) highlight that fintechs can obtain access to the broader customer base, and learn how to deal with financial regulations and access to banking licences. According to Drasch et al. (2018), only 2% of fintechs have a banking license. Banks enable market entry for fintechs by providing regulatory infrastructure, products, know-how, and funds (Bömer & Maxin, 2018; Drasch et al., 2018). Another aspect is to catch up with the new opportunities, which is essential for both banks and fintechs. The latter realised that the partnership with banks is necessary for them to grow and have access to a large base of banks’ customers (Bömer & Maxin, 2018; Drasch et al., 2018; Carbó-Valverde et al., 2021). Furthermore, fintechs want to access economies of scale, build user networks, and balance risks (Hommel & Bican, 2020). On the other hand, banks acknowledged that strategic alliances with fintechs are an opportunity to improve the digital services they offer (Hornuff et al., 2021).

Another group of motives for an alliance between banks and fintechs embrace the better adjustment to customer expectations, cost reduction, and the possibility of creating new services (Holotiuk et al., 2018). Hommel and Bican (2020) emphasize that making new services is connected with risk reduction, privacy, and data security. They also indicate a positive influence on bank performance and profitability, processes that are more convenient, higher efficiency and improvement in service quality, as the motives for banks to partner with fintechs. A strategic alliance supports bank efforts to save costs, reduce workload and focus on core activities (Klus et al., 2019). Hornuff et al. (2021) reveal that another reason for banks is to secure a competitive advantage. They indicate fintechs have developed as a better way to provide financial services. Furthermore, fintechs can give banks exclusive rights to use a specific application (or licence), which helps protect core businesses in banks. According to Klus et al. (2019), banks are afraid of the speed of change and are ready on business model evolution.

The strategic alliance between banks and fintechs can generate competitive advantages for both parties (Svensson et al., 2019). Holotiuk et al. (2018) and Klus et al. (2019) emphasize the role of learning as motivations for this kind of alliance. Incumbent banks and fintechs know that cooperation can help develop products and services, as well as being an opportunity for growth innovation (Hornuff et al., 2021). Sometimes, however, there are also some additional motives.

Alliance formation

It is highlighted in the literature that there are possible different forms of alliances between banks and fintech start-ups. Usually, a strategic alliance is based on an agreement between the involved parties and are distinguished different types of arrangements that may be based on: an ownership agreement, a contractual agreement or a licensing agreement (Lin & Darnall, 2015). Sometimes the term “alliance” is being used in a very lax way, and it defines many types of interactions between banks and fintech companies, like minority or majority investments, product-related collaborations, or other forms of cooperation between these two types of entities (Carbó-Valverde et al., 2021; Hornuf et al., 2021).

According to Russo & Cesarani (2017), strategic alliance formation should embrace three crucial phases: defining the reasons for the alliance creation, selecting the partners, and choosing the most appropriate form of governance. The motives for alliances might be different for every participating entity, and it is crucial that every partner achieves some benefits from the alliance. For example, banks support fintechs financially and help them overcome regulatory boundaries (Klus et al., 2019). Fintechs, on the other hand, help improve the efficiency of the banking services and raise the level of innovations of incumbent banks (Bömer & Maxin, 2018).

The second important aspect of alliance formation is the selection of partners. All participants must be attractive to the other participants. The criteria that must be fulfilled to become a suitable partner in a strategic alliance are presented in several research papers. Svensson et al. (2019) describe the detailed conditions of being seen as a legitimate strategic alliance partner. They create a list of necessary conditions partners must meet and highlight that organizational legitimacy is crucial for a successful strategic alliance. They also describe a framework of legitimating functions of alliances between a fintech start-up and an incumbent to meet the organizational legitimacy needs of each partner. Whipple and Frankel (2000) also highlight the need to meet partner expectations as a key factor of a strategic alliance. According to them, the critical success factors of strategic alliance can be enumerated: trust, senior management support, clear goals, ability to meet performance expectations, and partner compatibility (Whipple & Frankel, 2000). Russo and Cesarani (2017) demonstrate that the partner selection process for a strategic alliance should be considered through three criteria: complementarity, congruence, and compatibility. They argue that partners should provide complementary resources and be committed to achieving common, clear, compatible goals.

The third phase of alliance formation is choosing the most appropriate form of governance, the choice of which is connected with the alliance structure. The main decision is whether the alliance involves equity stakes or is without equity investment. Elmuti and Kathawala (2001) argue that the purpose behind alliance formation significantly decides on the choice of governance structure. Alliance objectives are generally treated as the crucial determiner of the governance structure. Sometimes, aspects like alliance management objectives and international partners prevail (Teng & Das, 2008). Another important aspect of alliance formation is having well-prepared and aware managers to manage alliances (Anand & Khanna, 2000; Drasch et al., 2018), as they can better provide the process from legitimation to hybridization.

The case of Banca Popolare di Cortona and NetFintech

In July 2021, Banca Popolare di Cortona (BPC) acquired a 9.99% stake in NetFintech (NF), an Italian fintech start-up founded two years before, operating under the Change Capital brand (ID3). This investment represented a fundamental step for the strategic alliance formation between an incumbent bank and a fintech start-up, with a deep impact in the financial eco-system of the two entities. Contextualizing the case in the framework previously elaborated, the different components of the strategic alliance formation are represented in the figure below (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The framework of strategic alliance formation between Banca Popolare di Cortona (BPC) and NetFintech (NF)

Characteristics of BPC and NF

Banca Popolare di Cortona S.c.p.a. (BPC) is a traditional local bank, founded in Cortona in Arezzo in 1881, that has legal form of limited cooperative company. It is the oldest, small-sized Banca Popolare operating in Italy which, inspired by the principles of popular credit, currently serves the communities residing in the area included between the provinces of Perugia and Arezzo and in particular those of the Valdichiana. Today, Banca Popolare di Cortona represents an important resource for the economy of the entire area on the border between Tuscany and Umbria, a solid resource with a capitalization ratio (TIER 1) close to 16% (ID1), above the minimum requirement required by the supervisory authorities. The bank is operating with 74 employees, total assets of over 500 million euros, customer loans for just under 300 million euros, and deposits of over 350 million euro (ID1). The Bank collects savings and exercises credit in its various forms, inspired by the principles of community credit. The cooperative base is composed by around 3000 shareholders, while the distribution network consists of ten branches, of which nine are in the province of Arezzo and one in the neighbouring province of Perugia (ID1). Within its evolutionary path, the Bank has grown by following its main goal to “be a bank serving the territory”, even maintaining a local company profile aimed to preserve a distinct role and identity in the community in which it operates, to satisfy customer needs and produce wealth in the reference area. It has a distribution network, which pays particular attention to small and medium-sized enterprises and cooperatives (ID4).

NetFintech S.r.l. (NF) is a limited liability company registered in Arezzo that operates in the development, production and marketing of innovative products and services with high technological value in sectors such as credit mediation (ID2). The Company has a lean organizational structure inspired by an agile business model framework, with no hierarchical levels among managers and an on-going process of open innovation, networking and technological advancements (CM1, CM3). NF represents a digital financial network, with an advanced approach as compared to traditional credit activities. The Company is a credit broker, operating under the Change Capital brand, which has developed an integrated digital services platform for corporate finance, to reduce the information asymmetry between supply and demand. Particularly, it has developed a digital platform (C2-Suite) equipped with a CCC (Cash Conversion Cycle) predictive algorithm, which allows access to multiple market solutions (fintechs, banks, insurtechs, etc.). Through a digital platform, the Company manages a virtual marketplace that enables the interconnection between SMEs and banks, intermediaries and other fintechs, focused on short and medium-long term lending (ID3). Today, the platform represents the crucial element of the business model, as it allows to get, by entering the VAT number, the company’s financial statement data and carry out an analysis of the financial profile and consequent funding needs (CCC) and the risk profile of the company.

NF has prepared a challenging growth plan that should operate in the main industrial and financial centres of the country, through an innovative organization, which uses coworking and peripheral hubs (ID3). In 2021, the Company established a Spanish branch, Change Capital Spain, a credit brokerage company wholly controlled by Change Capital.

Motivations for BPC–NF alliance

The BPC bank adopts a traditional business model, focused on credit intermediation with the aim to realize specific customer targets represented by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and families. The strategic motives that encouraged the bank to carry out the alliance were mainly referred to as several synergies related to the business opportunities origination and organizational hybridization. Particularly, the strategic goals refer to creating new distribution channels, through the introduction of new integrated solutions to promote a more personalized and effective offer for customers (ID4). Additionally, the alliance would encourage the digital transition, following the innovation changes in lifestyles and business processes and developing partnership with digital operators to integrate business approaches and philosophies (CM4, IS1). Finally, the alliance would serve to generate a new risk management model implementing the integration between the commercial area of the bank and other emerging crucial areas such as, finance, advanced data and analytics, and artificial intelligence. A potential extension of the banks’ geographical coverage in new territorial areas is also probable, through the creation of digital financial shops. The fintech model is capable of supporting significant growth in business volumes by benefiting from a flexible costs structure. Furthermore, it offers access to a synergistic context based on digitization and new ways of interacting, with the possible attraction of new talents (CM4, IS1).

The NF fintech start-up actually proposes the most suitable solutions in terms of product and partner originator that are present on the financial platform (ID2). In perspective, the intention is to allow the use of the platform by banking and financial operators, in order to directly manage the pre-investigation phase, offering value-added digital services such as, digital marketing, customs intelligence, legal tech solutions, business intelligence solutions, payment services (PISP), and currency exchange management (ID3). It also plans to offer corporate insurance solutions, through a digital platform (IVASS). Considering the investment plan and the expected results, the strategic alliance has been considered by NF to be a formidable opportunity to gain legitimacy, raising financial support for growth, accelerating its presence on the market, and integrating their innovative services with traditional channels (CM2, CM5, IS2). Indeed, one of the main objectives of the partnership for the start-up was to collaborate with a bank with more than 100 years of history, an important brand and a strong presence on the territory. From an industrial and commercial point of view, the alliance would allow an extension on territorial diffusion, gaining real market experience. For NF, the possibility of contacting the bank’s customers and exploiting the relationships has been evaluated as extremely important. The incumbent bank can offer a highly valuable lead qualification that can easily be transformed into turnover and thus economic efficiency of the Company. The branch manager has the information and historical knowledge of the customers, and this facilitates the Company in making profitable financing and, therefore, favouring its growth (CM5, IS2).

Alliance formation between BPC–NF

The process of alliance formation started with several informal meetings between the top management teams of BPC and NF, accompanied by the continuous involvement and increasing commitment of the respective board of directors that finally approved the strategic alliance (IS1, IS2).

As reported from the interviewees, a fundamental step in designing the alliance and evaluating the entities’ characteristics and alliance motivations was the involvement of an external, professional consulting firm, appointed by the incumbent bank to assess the strategic value of the fintech development plan and the level of technology innovation embedded in the digital solutions proposed (IS1, IS2).

The alliance formation was also influenced by the regulation conditions and the relevant institutional characteristics of the two entities. More specifically, two regulations have conditioned and bound the collaborations. From the BPC side, the alliance has been evaluated in compliance with the regulations issued by the Bank of Italy, the fundamental regulatory and control organism for all less significant Italian banks (IS1). From the NF side and its character of a credit brokerage institution, it has been the OAM regulations. According to these rules, the shareholding that can be assumed by banks in credit brokerage companies cannot exceed the limit of 9.99% (IS2). Additionally, there is a limit of participation in the credit brokers’ capital imposed on banks, in order to avoid a significant influence and maintain independence among entities, according to the new discipline of financial agents and credit brokers.

Another relevant step in alliance formation was the involvement of professional legal consultants that supported the two entities in designing the most appropriate contractual agreements. Particularly, the process of formal definition of the collaboration required several meetings with the top management teams and was structured to value at their best the joint strategic objectives of industrial and commercial long-term alliance, not limiting to the typical provisions of investments agreements (ID4, ID5). The business plan elaborated by NF has been considered a central part of the agreement, together with the protocol of collaboration aimed to assure a continuous interaction between BPC and NF for the hybridization of the organizational cultures and the optimal exploitation of the industrial and commercial partnership (ID5).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Critical success factors

The conducted research enables a discussion of the identified critical success factors in the context of former literature study. They are presented in the same order as considered in the framework of strategic alliance formation between Banca Popolare di Cortona (BPC) and NetFintech (NF).

Strategic alignment and hybridization

The analyzed case between BPC-NF demonstrates that a successful alliance requires deeper integration in many aspects. One of the fundamental success factors in this alliance formation was the mutual knowledge and respect of the partners’ mission, vision and core values that were analysed through informal communication between the fintech founders, the banks’ top management teams and the board of directors (CM2, CM4, CM5). Since the beginning, the shared mutual commitment for an alliance has not been limited to a financial partnership, valuing the presence of the bank on the territory and the consolidated relationships with its customers that support the commercial and industrial growth of Change Capital (IS1, IS2). Also, the regulations influenced positively the strategic alignment, especially with reference to the limit of 9.99% of the investment share. Limiting the equity investment and the power of influence of the incumbent bank on fintech start-ups created a greater possibility of respecting the partners’ characteristics without losing the nature of each entity (CM2). As reported by the interviewees, the main challenge was to bring together two worlds characterized by very different speed and business models to create new business proposals, increase long-term profitability and exploit the innovation opportunities. This was consistent with the shared strategic objective to activate a process of hybridization (CM4, IS1), making the two organizations coexist, collaborate and contaminate the respective organizational cultures. The BPC General Manager was highly focused on this strategic goal, specifying during the presentation of the alliance at the Fintech district located in Milan (CM4):

“We are now transforming into hybridizing geneticists, who have to combine pieces of DNA from the most unthinkable areas. Our mission impossible is the creation of a bank model that does not exist, that knows how to wisely combine the tradition inherent in the universal values - today of great relevance - elaborated in the 19th century by strongly inspired minds, such as Luigi Luzzatti; the values of cooperation, of the community, of that social engineering laboratory that led to the birth in Europe and in Italy of popular credit, with the positive and evolutionary values of digital transformation. Always, and in any case, remember that the governance of things must belong to the human race and never to machines, which are only an expression of it. Our commitment to Change Capital goes in this direction”.

Additionally, as reported during the interview, the alliance must be instrumental with respect to the objectives of both counterparties. It is necessary to create the right degree of alignment and overlap of needs that must be sought (IS1, IS2). For the bank, it is a question of meeting new technological and managerial processes, the fintech world needs the stability and solidity of the banking world, which represents the most physical part of the collaboration project. Each needs the other (CM4, IS1). The fintech start-up offers good ideas and technologies, and the bank a good business model to implement them, with the shared aim to have profitable market prospects.

Competence and experience in the real market and SME’s financial needs

Our research contributes to the current literature on this subject by defining the importance of competence and experience of the bank and fintech decision makers in relations with their customers (IS2). We also confirmed the significance of relationships in creating successful strategic alliances. As reported in the interview, the BPC General Manager found that one of the most valuable characteristics of making the mutual understanding and commitment to the alliance was the competence and experience in the traditional market held by the NF founders (IS1). Quite paradoxically, an innovative project based on disruptive technologies has to be supported by an expertise in real market dynamics, effective customer relationship and physical interaction. Only these conditions can realize the goal of offering access to a specialized digital platform through which the traditional bank products can be conveyed, as well as the possibility of accessing new forms and methods of lending (digital factoring, instant lending, etc.) and consultancy for SMEs (advisory, mini-bond, etc.), with positive effects for both partners (CM4, CM5, IS1, IS2). On the one hand, the incumbent can offer fintech products to its customers; on the other hand, the fintech marketplace can expand the customer base and achieve geographical diversification. A potential extension of the incumbents’ geographical coverage in new territorial areas is also included in the strategic goals through the creation of digital financial shops. The fintech model is capable of supporting significant growth in business volumes by benefiting from a flexible costs structure. Furthermore, it offers access to a synergistic context based on digitization and new ways of interacting, with the possible attraction of new talents. In such a context, the key strategic objective is to integrate digital and physical, as clearly reported by the fintech CEO during the event at the Fintech district (CM5):

“The Bank’s entry into the capital of our Company, as well as being a reason for personal pride and great trust in our customers and business partners, is the concrete sign of the synergy and collaboration that can arise from the combination of digital and traditional, all in support and to the advantage of Italian SMEs”.

Cultural value and territorial closeness to create trust and commitment at the top governance level

The research provides deeper practical knowledge about cooperation between a bank and a fintech start-up in a given territory (CM3, IS1, IS2). The two entities involved in the alliance operate in the same province, characterized by a traditional productive system mainly formed by SMEs and operating with a deep link with cultural values and territory, quite far from the most innovative financial centres of Italy. As emerged from the interviewees (IS1, IS2), the territorial proximity of people involved in the alliance formation accelerated the mutual trust and created a positive commonality of intents, especially at top governance level. As specified by the banks’ General Manager, the realization of the partnership mostly depends on the organizational level that plans the collaboration project (IS1). The higher the level of the organization, the more it is possible to have a broad and complete vision of the integration, both in terms of staff commitment and for the involvement of the technological and market management components, both indispensable. A fundamental aspect concerns the contamination of the two worlds. On the one hand, collaboration cannot stop at the purely technological aspect as the success of these collaborations occurs when the right mix is created between tradition (bank) and innovation (fintech), because neither one nor the other going it alone is able to guarantee success (CM2, IS2). The main issue is to find the right combination, putting two worlds in relation that normally do not speak. On the one hand, the traditional world is structured and constrained based on complaints and regulations and has a mentality that is not always up-to-date, but it is orderly and stable. On the other hand, there is a fintech that is more flexible, innovative, dynamic and faster, but also less stable. At least it is important to approach them from a cultural point of view and to speak the same language (albeit with different dialects) (IS1).

Professionalism in strategic assessment and contractual agreements

The former literature highlighted the role of internal commitment, but the success of strategic alliances also depends on external factors. The case demonstrates that the alliance formation required a professional intervention from external consultants holding the suitable expertise in fintech strategic evaluation and corporate regulatory issues (ID4, ID5). As emerged from the interviewees, the technology assessment and the contractual formation of the alliance represented two fundamental aspects for the strategic planning of the partnership and the regulation embedded in the contractual agreements (IS1, IS2). Particularly, not limiting the formal setting to an investment agreement created the right premise to translate the mutual commitment on strategic alignment in an operational agenda to realize the hybridization of organizational cultures and innovation of financial services (CM4). Some strategic areas of the two entities have been involved in the alliance regulations, concerning the common initiatives to be implemented: digital marketing and strategic marketing, fintech lending, staff training and digital open banking initiatives (ID5). Also, the development of in-depth sessions on specialized topics in the field of fintech/digital banking were explicitly mentioned in the agreements, as well as planning meetings with the main players of the Italian financial and banking system, organization of thematic meetings with local SMEs, potential initiatives for specific industries (i.e. agri-food, textile, wine, etc.), with the aim of creating a value financial eco-system integrated with the real economy needs of the territory (ID5).

The case confirms the previous theoretical analyses that the trust in people and the professionalism with which the contractual agreements were made, supported by professional consultants, who did not neglect the formal and substantive aspects of the agreement, is fundamental.

Research implications

The research can be treated as a contribution to the financial ecosystem related literature. It describes the situation where traditional industry boundaries have been broken down leading to interdependence and symbiotic relationships. Our research provides three main contributions. The first contribution of the article to the literature on technology-driven transformations of the banking sector and bank–fintech start-up cooperation is the research framework. The framework bridges the research gap in the literature and explains the motivations of a strategic alliance between banks and fintech start-ups. The second contribution is the unification of the research framework with the alliance between BPC-NF. The performed verification finds reference to the literature on the research subject. The third contribution comes from the fact that our research is related to cooperative banks. Most of the research related to the incumbent banks – fintech start-ups are connected with commercial banks, whereas we focused on cooperative banks, which play an important role in the Italian banking sector. All of these areas require further, in-depth research in the future.

The research suffers some limitations related to the difficulty to generalize the results derived from the contextualization of the strategic alliance implemented, as usually highlighted for the case study research. First of all, the case considers a cooperative bank, whose governance and management processes are influenced by the need to safeguard and value the territory and the shareholder base in a collaborative logic. Geographical diversification can bring new dimensions of the strategic alliance cooperation. It is also important to compare the strategic success factors identified for cooperative banks with the same factors identified for commercial banks. Secondly, the entities involved in the alliance are characterized by relatively small and local dimensions. This may have impacted on the particular attention and care the governance and management of the two entities invested in the alliance design and implementation, confirming the particular value of the integration between the theoretical pillars of the framework elaborated. However, as Yin (2014, p. 48) counters, case studies are not designed to provide statistical generalizations but instead deliver analytical generalizations that offer theoretical explanations that researchers can apply to similar cases.

Managerial implications

The research has some managerial implications about the strategic alliance between incumbent banks and fintech start-ups. In fact, when the entities decide to form a strategic alliance, they should take into account several aspects that are treated as the critical success factors. Some of them were discussed in this study. However, they lead to two crucial managerial implications. Firstly, when defining a strategic alliance between incumbent banks and fintech start-ups, not only technological exchanges should be considered. Designing an alliance should also involve such factors as top levels of governance of the participating entities. In turn, the governance is a derivative of their mission, culture, processes, and proper commitment at the governance level. Secondly, the process of alliance formation is very important. Managers have to be very sensitive to define the collaboration and create a good agreement. Self-regulation is a challenge and it is essential for all participating parties to create a good strategic agreement. A properly defined agreement will decide on the success of their alliance.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Roberto Calzini, General Manager of Banca Popolare di Cortona, and Francesco Brami, CEO of NetFintech, for their kind availability and their precious contribution to the development of this paper.

References

Abdollahbeigi, B., & Farhang, S. (2021). A study of strategic alliance success factors. International Journal of Economics and Management Systems, 36(2), 21-28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2000.tb00248.x

Acar, O., & Çıtak, Y. E. (2019). Fintech integration process suggestion for banks. Procedia Computer Science, 158, 971-978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2019.09.138

Adner, R. (2017). Ecosystem as structure: An actionable construct for strategy. Journal of Management, 43(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316678451

Akpotu, Ch. (2016). Strategic alliance and operational sustainability in the Nigerian banking sector. Review of Social Sciences, 1(8), 44–50. https://doi.org/10.18533/rss.v1i8.57

Albers, S., Wohlgezogen, F., & Zajac, E. J. (2016). Strategic alliance structures: An organization design perspective. Journal of Management, 42(3), 582–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313488209

Amin, G. R., & Boamah, M. I. (2022). Modeling business partnerships: A data envelopment analysis approach. European Journal of Operational Research, 305(1), 329-337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2022.05.036

Anand, D., & Mantrala, M. (2019). Responding to disruptive business model innovations: The case of traditional banks facing fintech entrants. Journal of Banking and Financial Technology, 3(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42786-018-00004-4.

Angelini, P., Di Salvo, R., & Ferri, G. (1998). Availability and cost of credit for small businesses: Customer relationships and credit cooperatives. Journal of Banking & Finance, 22(6), 925–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266(98)00008-9.

Appleyard, L. (2020). Banks and credit. In J. Knox-Hayes, & D. Wójcik (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Financial Geography (pp. 379–99). New York: Routledge.

Arslan, O., Archetti, C., Jabali, O., Laporte, G., & Speranza, M. G. (2020). Minimum cost network design in strategic alliances. Omega, 96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2019.06.005

Arslanian, H., & Fischer, F. (2019). Fintech and the future of the financial ecosystem. In H. Arslanian & F. Fischer (Eds.). The Future of Finance: The Impact of FinTech, AI, and Crypto on Financial Services (pp. 201-216). Cham: Springer.

Babajide, A. A., Oluwaseye, E. O., Adedoyin Isola Lawal, A. I., & Isibor, A. A. (2020). Financial technology, financial inclusion and MSMEs financing in the south: West of Nigeria. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 26(3), 1-17. Retrieved from https://www-1proquest-1com-1e7wvbydx02bb.hps.bj.uj.edu.pl/docview/2515190946?accountid=11664.

Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544-559.

Benziane, R., Roqiya, S., & Houcine, M. (2022). Fintech startup: A bibliometric analysis and network visualization. International Journal of Accounting & Finance Review, 11(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.46281/ijafr.v11i1.1715

Bertocco, G. (2004). Are Banks Really Special? A Note on the Theory of Financial Intermediaries. Department of Economics, University of Insubria. Retrieved from https://www.eco.uninsubria.it/RePEc/pdf/QF2004_32.pdf

Bhagat, A., & Roderick, L. (2020). Banking on refugees: Racialized expropriation in the fintech era. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(8), 1498–1515. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20904070

Bilotta, N. (2017). The Italian banking system. Moral Cents: The Journal of Ethics in Finance, 6(2), 2-13.