Received 1 April 2020; Revised 2 June 2020; Accepted 20 June 2020.

This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

Valentina Ivančić, Ph.D., Domovinskih žrtava 20, 52466 Novigrad, Croatia, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it., corresponding author.

Lara Jelenc, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Rijeka, Ivana Filipovića 4, 51000 Rijeka, Croatia, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Ivan Mencer, Ph.D., Full Professor, Janka Polić Kamova 95a, Rijeka (Croatia), e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Abstract

Purpose: Although the implementation process involves employees from different hierarchical levels, previous research on the implementation topic focused mostly on a top management perspective, omitting the perspective of lower hierarchical levels. We believe that employees from different hierarchical levels perceive differently the way the implementation process is carried out because of many intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Considering the primary role of lower hierarchical levels during the implementation process, we decided to include lower levels of management and operatives in our research. Methodology: We investigate the way employees from different hierarchical levels perceive the implementation process. The implementation process in our research was evaluated using four implementation factors: 1) People, 2) Resources allocation, 3) Communication, 4) Operational planning & control. We sent the questionnaire to all large Croatian enterprises (396) and gathered 208 questionnaires from 78 enterprises. Findings: The research findings confirm that the evaluation of key implementation factors differs significantly between hierarchical levels in two of the four identified factors: 1) Communication and 2) Operational planning & control. Frontline managers and operatives mostly consider the instructions for implementing the strategy too vague and unclear, their suggestions not taken into account, the communication generally too slow, what creates confusion and reduces the efficiency in coordinating operational tasks and introducing potential changes. Implications for theory and practice: Although we proved the statistically different perception about two out of four implementation factors, we contributed in a way to point out that this stream of research, with multiple factors and multiple respondents from different hierarchical levels, should be taken into consideration in future research about strategy implementation. Top managers should include feedback from lower hierarchical levels in order to grasp the pitfalls of strategy implementation. This study highlights the operational problems that might occur such as vague or slow communication, budget discrepancy, inadequate definition of timeline for activities and its dynamics, and ways to measure performance during strategy implementation. We believe that the research results are beneficial for academics and consultants when creating teaching and training programs for future managers about strategy implementation. Originality and value: Based on the analysis of the literature review and the research findings, we develop a new implementation model with questionnaire to analyze the way employee from different hierarchical levels perceive the implementation process.

Keywords: strategy implementation process, key implementation factors, hierarchical levels, employees’ perspectives on the strategy implementation process, large Croatian enterprises.

INTRODUCTION

Managers spend billions of dollars on consulting and training in the hope of creating successful strategies. But all too often, successful strategies do not translate into successful performance. Strategy implementation ranks high on top managers’ agendas, but it is a topic that has not received sufficient attention in academia. It seems like academics have assumed that if an enterprise has a strategy, it gets implemented automatically. But when talking with managers, it is obvious that the process of implementation does not go smoothly. Most managers admit that their organization is experiencing significant problems with translating their strategies into concrete activities and results (Verweire, 2018).

Research on The Times 1000 conducted in 2001 points out that 80% of the interviewed managers confirm they have an appropriate strategy, but only 14% think that the strategy is implemented appropriately (Cobbold & Lawrie, 2001). Only four years later, the journal The Economist published results, according to which 57% of the enterprises were not successful in implementing strategy (Allio, 2005). Furthermore, the research of Marakon Associates and The Economist Intelligence Unit consultancies on a sample of 197 members of top management shows that, due to problems in implementation, only 63% of enterprises accomplished their planned goals (Mankins, 2005). McKinsey, one of the world’s leaders in implementation consultancy, notes that even 70% of change programs fail to achieve their goals, largely due to employee resistance and lack of management support (Ewenstein, Smith, & Sologar, 2015).

As part of the strategic management field, the research on strategy implementation has moved away from practice and does not have a need to serve managers (Whittington, 1996). Strategy implementation is happening in practice and that is where we need to seek new efficient solutions (Tovstiga, 2010). The analysis of strategy implementation should start with people, their perspective, their character, and their drive (Zafar, Butt, & Afzal, 2014). They are critical for successful strategy implementation and they are the starting point when things go wrong. The research focus should be on their thoughts, experience, and capabilities (Asmuss, 2018).

Strategy implementation assumes implementing a strategic plan according to the predefined elements and scheduled timeframe. Those elements are the essence of implementation and, during the process, should be carefully monitored. The research (Beer & Eisenstat, 2000; Radoš, 2006; Pučko & Čater, 2008; Brinkschröder, 2014; Harrison, 2017) showed that the lack of systemic control over these elements is the most common mistake in strategy implementation.

The additional thing that makes strategy implementation more complex is the necessity of coordinating a large number of people on different hierarchical levels and with varying functions of business (Candido & Santos, 2019). Strategy is no longer positioned within a limited group consisting of the top management team, instead it can potentially involve any internal and external organizational actor whose actions can be identified to be of relevance for strategic outcomes (Asmuss, 2018). An enterprise can be seen as interconnected sets of processes – and processes are a collection of tasks and activities that together transform inputs into outputs (Verweire, 2018).

Traditional studies on strategy implementation and strategic management processes, in general, focus mainly on the top managers’ perspective (Simons, 2013), omitting the key role of middle managers and operatives (Floyd & Lane, 2000; Grönroos, 1995; Schaap, 2006; Kalali et al., 2011; Anchor et al., 2012; Kownatzki et al., 2013). Although the top management perspective is critical because it emphasizes strategic thinking and endeavor, it is mostly the lower-level employees who participate in the implementation process. In order to ensure efficient use of resources and maintain the planned dynamics of strategy implementation, it is vital that employees, at all hierarchical levels, understand what is expected of them, what is the objective of the implementation, what is the expected dynamics of tasks and what are the key factors that need special attention (Noble, 1999a). A failure to understand or approve of some of the key implementation factors may prolong and/or increase the cost of strategy execution (Noble, 1999). Without the integration of knowledge, information and experience brought in by all hierarchical levels, the process of strategy implementation cannot be successful (Hrebiniak, 2006; Mantere, 2008; Shimizu, 2017).

Exploring the opinions of lower hierarchical levels, i.e. those participating in the implementation process on a daily basis, would enable practitioners and strategists to get a complete picture of the implementation obstacles and needs arising within the implementation process when it comes to resolving disagreements, reaching an operatives’ consensus, identifying required skills and creating training programs (Floyd & Wooldridge, 1992; Rapert, 1996; Noble, 1999a; Dooley et al., 2000; Heracleous, 2003).

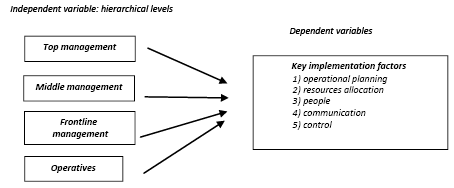

So, the first identified research gap is the lack of a systematic consideration of key implementation factors. We addressed this by gathering feedback on the level of satisfaction with implementing each of the implementation factors. The list of key implementation factors is based on Okumus (2003) theoretical research, who stressed the systematic approach of looking at all crucial implementation factors. Key implementation factors defined in his model are: 1) People, 2) Resources allocation, 3) Communication, 4) Operational planning, 5) Control.

According to the second identified gap, i.e. the lack of strategy practitioners’ perspective research, we decided to develop our research with a special focus on all employees involved in the implementation process. When implementing strategy, top, middle, frontline management and operatives are involved, and we decided to ask all of them about the implementation factors. In each enterprise, we had four respondents, one from each hierarchical level.

The aim of the paper is to examine how employees from different hierarchical levels evaluate the adequacy of key implementation factors, respectively evaluating how each of the respondents from different hierarchical levels is satisfied with the specific implementation factors. We believe that viewing the implementation process through different hierarchical levels and the interrelation among the different influencing factors is the starting point for a comprehensive analysis of the implementation process. This approach enables one to integrate and compare the perspectives of different actors within the implementation process, link the strategic and operational perspective, look for potential sources of problems and determine the assumptions on which new strategy implementation model has to be developed.

The research was conducted in large enterprises in the Republic of Croatia. Large enterprises in Croatia represent 0.3% of the total number of enterprises, employ 30.5% of the work force, create 41.5% of value added, and 97.5% of net profit (Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Croatia, 2016). By including all industries in the sample, it provided 396 large enterprises in the Republic of Croatia.

The paper is organized into five sections. After the introductory section, the second section provides a literature overview and develops the research model, research questions, and hypothesis. Section 3 describes the research methodology and presents the sample, the research instrument, and the research results. In the fourth section, we discuss the empirical findings and their implications. The paper concludes with a conclusion, which analyzes research gaps and proposes guidelines for future research.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Strategy implementation is the process that involves the execution of the necessary tasks or activities to obtain a result over what has been planned (Ramadan, 2015). David Garvin says, successfully implementing and executing strategy involves delivering what is planned or promised on time, on budget, at quality, and with minimum variability – even in the face of unexpected events and contingencies (Miller, 2020).

While it is agreed that strategy formulation is relevant for business success, to date, little attention has been paid to its actual implementation, i.e. to the concrete steps needed to translate sustainability strategy into practice (Klettner et al., 2014; Engert & Baumgartner, 2016). A high percentage of failure in implementing strategy in practice urges research to move the focus from strategy formulation to strategy implementation (Blahová & Knápková, 2011; Hassan, 2016). Tawse et al. (2019) posit that one reason for the ineffective transition from strategy formulation to strategy implementation is that planning is associated with a different set of thought processes and emotional experiences than is required for strategy implementation.

As employees implement strategy from different hierarchical levels, we think there is a gap in the literature that includes not only the attitudes of the top management team (Heracleous, 2003; Kalali, 2011) but also the attitudes of frontline managers and operatives. In the last couple of years, there has been a slight tendency to include middle-level managers in the research on strategy implementation (Salih & Doll, 2013; Darkow, 2015; Chowdhury, 2016; Johansson & Svensson, 2017), yet lacking ones including front line management and operatives.

Gibson et al. (2019), who introduced the notion of the hierarchical erosion effect, emphasize that employees within the same enterprise usually have heterogeneous interests and perceptions. Their study argues that individual perceptions about specific practices can differ according to his/her position in the hierarchical structure. That means an enterprise might have a low dispersal of views across employees of similar levels, but a significant difference between the views of senior executives, middle-level managers, frontline supervisors, and non-managerial employees.

In our view, there is a twofold contribution of including different hierarchical levels of management in the research. The first one is that the comparison of perspectives from different hierarchical levels could contribute to revealing obstacles and problems for successful strategy implementation. For example, it could be problems like not understanding the strategy at lower hierarchical levels, slow flow of information from top to bottom and from the bottom up, weak dedication of employees for achieving business results. The second one is linked to the way strategic plans are developed. In the last two decades, there has been growing attention paid to bottom-up approaches and alternative ways on how to develop strategy. In more complex and turbulent times of doing business, strict strategic plans lose their relevancy (Schaap, 2012). Additionally, the role of middle-level and frontline managers is becoming more relevant due to the experiences and skills that could be helpful in improving the strategy itself during the implementation process (Noble, 1999; Hrebiniak, 2006). Pereverzieva (2020) emphasized that it is important to understand how personal interactions occur in the enterprise. The issue of co-existence and interactions between people within a particular system becomes of particular importance. From the managerial perspective, an efficient and united team envisages not only the automatic distribution of roles and labor functions but also the availability of interaction, collaboration, support and assistance on the way to the common goal. Unfortunately, there is often a lack of cooperation between hierarchical levels (Alexander, 1985; Al Ghamdi, 1998; Beer & Eisenstat, 2000; DeLisi, 2001; Shah, 2005; O’Regan & Ghobadian, 2007; Wheelen & Hunger, 2010; Kalali et al., 2011) and a lack of systematic analysis of crucial implementation factors.

Tiemersma (2015) and Wolczek (2014) emphasize that top managers do not sufficiently collaborate with mid-level managers, although the latter play a key role in the strategy implementation process by translating top management’s expectations into the daily workload of their subordinates. Top managers usually do not coordinate and integrate activities between different levels and business functions in a proper manner (Al Ghamdi, 1998; Hrebiniak, 2006; Pučko & Čater, 2008; Koseoglu et al., 2009, Kalali et al., 2011) and the responsibilities during the implementation process are not clearly defined (Hrebiniak, 2005; Shah, 2005; Radoš, 2011; Behery et al., 2016). In addition to this, top managers fail to collect employees’ suggestions and develop appropriate programs to improve employees’ skills and competencies needed for the implementation of new strategies or quick adaption to changing conditions (Shah, 2005; Pučko & Čater, 2008; Heathfield, 2019), which is why employees performing operational tasks are not ready to accept and execute what is expected of them. Different perceptions about implementation needs and barriers can lead to employees feeling misunderstood, exhausted, disengaged, and stressed. In these situations, individuals commonly start to resist the intended changes; promote self-serving agendas; obstruct intra- and inter-departmental communication; deplete personal and enterprise resources, and generally undermine the success of the planned strategic decision (Bouckenooghe, 2012).

The understanding of the differences in the perception and interpretation of key implementation factors is the first step in defining the framework for developing a model that could help monitor the strategy implementation process, maintain the focus on planned tasks and implementation dynamics, align employees from different levels performing different business tasks, and adhere to the planned budget.

The proposed hypothesis stems from the starting point that people at different hierarchical levels evaluate key implementation factors differently because, given the set of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, they perceive differently what shortcomings within the implementation process impede it to be carried out qualitatively and in line with the predicted dynamics.

This paper builds on the theoretical model of key implementation factors proposed by Okumus (2003). Key implementation factors include:

- Operational planning: the process of initiating the project, and the operational planning of the implementation activities and tasks. Operational planning has a great deal of impact on allocating resources, communicating, and providing training and incentives. The key issues to be considered are preparing and planning implementation activities, defining work procedures and scheduling tasks, participation and feedback from different management levels and functional areas, initial pilot projects and the knowledge gained through them, and the timescales of making resources available and budgeting.

- Resource allocation: the process of ensuring that all necessary time, financial resources, skills and knowledge are made available. It is closely linked with operational planning and has a great deal of impact on communicating and on providing training and incentives. The key issues to be considered are the procedures of securing and allocating financial resources, the relationship between price, quality and timeliness of resources, information and knowledge requirements needed to implement a new strategy, and the time available to complete the implementation process.

- People: recruiting new staff, providing training and incentives for relevant employees. The key issues to be considered are recruitment of relevant staff to accommodate the implementation needs, the acquisition and development of new skills and knowledge, the adoption of the necessary training activities to prepare key employees for the change, and the provision of incentives.

- Communication: the mechanisms that send formal and informal messages about the new strategy. The main issues are the use of clear messages when informing relevant people within and outside the enterprise, the implications of (not)using multiple modes of communication (top-down, bottom-up, lateral, formal/informal, one time or continuously), and the impact of organizational culture and structure on the communication process.

- Control: the formal and informal mechanisms that allow the efforts and results of implementation to be monitored and compared against predetermined objectives. The main issues are monitoring activities carried out during and after the implementation process, alignment with operational plans, providing feedback on implementation progress from implementation actors, and establishing corrective actions if necessary.

It is necessary to take into account that the number of hierarchical levels depends on enterprise size and the applied organizational structure. Large enterprises usually have at least one level between the top and the bottom of the hierarchical pyramid. In our research, we identified four hierarchical levels. Top management creates and directs the strategy path according to the “big picture,” i.e. the wide range of information it collects, selects, and analyzes from inside and outside the enterprise. Middle management usually represents the change facilitator, removing obstacles like contradictory goals, and ensuring required resources (Aaltonen, 2001). It manages the information flow in both directions: top-down and bottom-up (Huey, 1994; Hrebiniak, 2006). Middle managers are usually the head of dislocated strategic business units, functional departments, or the head of key enterprise project initiatives. They deploy strategic initiatives to concrete job positions. Frontline management covers different tasks such as team leader or shift leader depending on enterprise needs and cooperation with middle management level. For sure, together with operatives, it composes the core of the strategy implementation team. Operatives are the direct performers, the strategy executors. They follow the instructions and suggestions from superior levels and transform plans into actions through day-to-day operations.

To summarize, we would like to set out three research questions:

RQ1) Does the perception of key implementation factors differ with

respect to the position of respondents within the enterprise?

RQ2) Is the hierarchical level a crucial variable for that differentiation?

RQ3) Could this approach be helpful for managers to improve strategy

implementation?

Based on the research questions, we define the research model in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The research model

Source: Authors’ work adapted from Okumus (2003, p. 876).

In line with the mentioned literature review, defined research goal, and research questions, we define the following hypothesis:

H: There is a statistically significant difference in the evaluation of key

implementation factors between employees from different hierarchical

levels.

The research instrument

The questionnaire is created based on the research on the key implementation factors defined by Okumus (2003), whose research gave the guidelines on what to include within each of the specific implementation factors. Based on that research, we created the dependent variables and defined specific items.

In the strategic management literature, the most common methods are questionnaires, interviews, and case study methods. We selected the questionnaire as the most appropriate method for our research. This was due to the fact that we wanted to include lower levels of management (as recommended in previous research, e.g. Alexander, 1985; Nutt, 1986; Rapert et al., 1996; Noble, 1999a; Hassan, 2016), a number of the factors influencing the implementation process (Noble, 1999; Okumus, 2001; Li et al. 2008; Schaap 2012), and as many of the 396 large enterprises in the Republic of Croatia as we could in the sample. We asked respondents to evaluate their level of satisfaction on a variety of different critical factors of implementation. With a Likert type of scale, we gave respondents the possibility to evaluate the intensity of satisfaction with the specific implementation factor from 1 – very unsatisfied to 5 – very satisfied.

Table 1. Key implementation factors – the questionnaire

|

Key implementation factors |

Rate the level of your satisfaction with the following statements, which describe the current state of strategy implementation in your enterprise. 1 – very unsatisfied, 2 – unsatisfied, 3 – neutral, 4 – satisfied, 5 – very satisfied |

|

Operational planning |

|

|

Resources allocation |

|

|

People |

|

|

Communication |

|

|

Control |

|

Respondents who did not understand the question or did not know, or did not want to express their opinion were asked not to circle any answer.

The respondents were asked to rate the questions on five-point Likert scales. Higher scores indicate that respondents consider that the implementation process is carried out in a proper manner. In Table 1, we present the questionnaire.

In order to determine face validity, we gave the questionnaire to five academics in the field of management. Their role was to give us feedback on how appropriate and clear the terminology used in the items was. After that, we conducted pilot research on five enterprises. Based on the feedback, we did small corrections to the questionnaire and then conducted the research on the whole sample.

The list of enterprises and contacts were taken from the database of the Croatian Chamber of Economy. The first contact with the enterprises was established by phone call or e-mail with the human resource department or with corporate governance. They directed us to employees on different hierarchical levels to whom we delivered the questionnaire. After making the first contact, the questionnaire was sent by e-mail or post, depending on the instruction given by the contact person from each enterprise. The questionnaire was coupled with a letter explaining the goal of the research and the way the questionnaire could be sent back. The empirical research lasted for five months. We managed to get 208 responses from 78 firms. Internal reliability had a value of 0.95 of Cronbach’s alfa for the whole research sample and internal reliability of specific variables and items are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Reliability and validity of the research instrument

|

Variables |

People |

Resources |

OPPC |

COMM |

|

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for each variable separately |

0.89 |

0.90 |

0.87 |

0.87 |

|

Number of items |

7 |

5 |

6 |

8 |

|

Explanation of the variance |

62.43% |

|||

|

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin and Bartlett test |

0.936 |

|||

|

Chi-square |

3467.74 |

|||

|

Degrees of freedom |

406 |

|||

|

Significance |

.000 |

Note: N=208. Extraction: principal component analysis. Rotational method: Oblimin with Kaiser normalization. Rotation converged into 14 iterations. Deleted values below 0.30.

OPPC = Operational planning and control

COMM= Communication

Analyzing the intercorrelation matrix, for the Confirmatory factor analysis, we remove all items with a loading factor below 0.4 and proceed with four variables: 1) resources allocation, 2) communication, 3) people, and 4) operational planning and control. The results of our research indicated that in the operationalization of key implementation factors, the variables of operational planning and control are combined into one.

Apart from key implementation factors, we asked respondents to make a note about the hierarchical level they belong to (top, middle, frontline management and operatives), years of age (number), years of experience in the existing enterprise (number), ownership form (possibility to mark > 50% in private ownership or > 50% in public ownership), market of placement (possibility of mostly domestic or mostly foreign market) and industry sector (according to Statistical classification of economic activities from 2007– NACE Rev. 2).

Sample size and data collection

The size of the enterprises in Croatia is defined by the Act of Accounting. Firms are defined by exceeding two out of the three criteria: (1) more than 250 employees, (2) the amount of assets equal or higher than 150.000.000 kunas, (3) annual income exceeds 300.000.000 kunas.

According to the Croatian Chamber of Economy there were 396 registered large enterprises and that presented a sample frame for us. We received 208 questionnaires from 78 enterprises, with a response rate of 19.75%.

There are two reasons why large enterprises were selected for the sample. The first reason is that large enterprises have a strategic impact on the whole economy. The second one is that strategy implementation is more complex in large enterprises for the following reasons: (1) larger number of employees and (2) larger number of different hierarchical levels, business functions, and dislocated business units. In those situations, strategy implementation demands, from top managers, the coordination of several influential factors, stakeholders, and different environmental contexts.

Data analysis

The demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 3, such as the structure of respondents by hierarchical level, average age of the respondents by hierarchical level, years of respondents’ experience in the respective enterprise, form of ownership, placement market, and industry.

Table 3. Demographic characteristics of the sample

|

N=208 respondents |

N=78 enterprises Number of large active enterprises per industry/% of enterprises that have completed the questionnaire in relation to the total number of active enterprises within the industry |

||

|

Hierarchical level Top management Middle management Frontline management Operatives No answer Length of employment with the respective enterprise 0–4 y. 5–9 y. 10–14 y. 15–19 y. 20+ y. No answer Ownership Private Public Major placement market Domestic Foreign Average age Top management Middle management Frontline management Operatives |

59 (28.4%) 70 (33.7%) 49 (23.6%) 30 (14.4%) 38 (18.3%) 48 (23.1%) 44 (21.2%) 28 (13.5%) 47 (22.6%) 3 (1.4%) 166 (80%) 42 (20%) 99 (47,5%) 109 (52,5%)

45 44 41 36 |

A - Agriculture, forestry and fishing B - Mining and quarrying C - Manufacturing E - Water supply, sewerage, waste management F - Construction G - Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles H - Transporting and storage I - Accommodation and food service J - Information and communication M - Professional, scientific and technical activities R- Art, entertainment and recreation |

14 (7.14%) 3 (100%) 144 (22.22%) 13 (23.08%) 30 (13.33%) 81 (12.35%) 30 (30%) 18 (72.22%) 12 (8.33%) 5 (20%) 8 (12.5%) |

The largest number of responses (questionnaires) was completed by middle management, followed by top management, frontline management, and operatives. We grouped the employees’ experience into five-time categories. We have respondents with a starting (up to 4 years), short (between 5 and 9 years), medium (between 5 and 14 years), long (from 15 to 19 years), and very long (over 20 years) work experience within the respective enterprises. Most of the sample enterprises are privately owned (80%). The distribution of enterprises according to the major placement market is balanced. Namely, 47.5% of the sample enterprises market their products/services primarily in the domestic market, while 52.5% are in foreign markets.

The most representative enterprises in the sample are those in the manufacturing industry, followed by enterprises in the tourism industry and enterprises in wholesale and retail trade. The survey included 19.75% of the total number of large enterprises in the Republic of Croatia. According to economic activity, the representation of individual industries in the total population indicates the representativeness of the sample of enterprises in Mining and quarrying, Manufacturing, Water supply, sewerage and waste management, Transporting and storage, Accommodation and food service, and Professional, scientific and technical activities.

As mentioned above, depending on the organizational structure selected, each enterprise has different hierarchical levels. Table 4 shows the number of enterprises from which we obtained responses from all four hierarchical levels. We obtained responses from three levels, two levels, and only one level.

Table 4. The structure of involved hierarchical levels

|

Involved hierarchical levels |

Number of enterprises |

|

Four hierarchical levels |

5 |

|

Three hierarchical levels |

59 |

|

Two hierarchical levels |

10 |

|

One hierarchical level |

4 |

|

Total |

78 |

In Table 5, there is an overview of the average level of satisfaction for each implementation factor per specific hierarchical level.

According to the average score for each of the four key implementation factors, it can be concluded that people and resources are the ones managed less successfully. Table 6 summarizes the results of the analysis of the relationship between the evaluation of key implementation factors (dependent variable) and the hierarchical position of respondents (independent variable). A simple variance analysis test was applied.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation)

|

Hierarchical levels |

People |

Resources allocation |

Operational planning & control |

Communication |

|

Top management |

3.69 (.72) |

3.71 (.73) |

4.03 (.54) |

4.64 (.73) |

|

Middle management |

3.57 (.73) |

3.54 (.84) |

3.82 (.72) |

4.38 (.88) |

|

Front line management |

3.47 (.66) |

3.60 (.83) |

3.70 (.63) |

4.24 (.74) |

|

Operatives |

3.37 (.62) |

3.43 (.75) |

3.77 (.49) |

4.17 (.72) |

|

Total |

3.55 (.70) |

3.59 (.79) |

3.85 (.63) |

4.39 (.80) |

Note: values in parentheses show standard deviation.

Table 6. Perspective on key implementation factors depending on the hierarchical level of the respondents

|

People |

Resources allocation |

Communication |

Operational planning & control |

|

|

Respondent's hierarchical position |

F (3,200) =1.654 p=0.178 |

F (3,200) =0.903 p=0.441 |

F (3,200) =2.772 (0.3976)13 (0.4679)14 p=0.043 |

F (3,200) =3.236 (0.3345)13 p=0.023 |

Note: values in parentheses show statistically significant Mean differences between hierarchical levels.

Post Hoc test: Bonferroni test provided for variables People, Resources and Operational planning and control, Dunett T3 for variable Communication; 1–Top management, 2 – Middle management, 3 – Front line management, 4 – Operatives.

Considering the hierarchical position of the respondents, there are statistically significant differences in the evaluation of the Communication variable and the Operational planning & control variable, which requires the application of corresponding post hoc tests. In the case of the Communication variable, due to the inhomogeneous distribution of data, the non-parametric Dunnett T3 test was applied while, due to the homogeneous distribution of data in the case of the Operational planning & control, we applied the Bonferroni test. We found statistically significant differences in the way respondents rated the communication process (F (3, 200) = 2.72; p=0.043, R2 = 0.47, R2 adj. = 0.33), and the operational planning & control processes (F (3, 200) =3.23; p=0.023, R2=0.41, R2 adj.=0.26).

Regarding the Communication variable, statistically significant differences were observed between the evaluation given by top management and that of frontline management and operatives. There is no statistically significant difference between top management and middle management evaluation. Operatives gave the lowest score, lamenting that communication is not clear and timely, and that the communication channels are not well established. Bottom up communication is also neglected and there is no active participation of lower hierarchical levels in the formulation stage.

When considering Operational planning & control, the evaluation of frontline management is statistically significantly different from that of top management in evaluating the adequacy of implementation process dynamics, adherence to budget, clarity of priorities and procedures, the role of middle management, and alignment of partial plans with the strategic plan.

DISCUSSION

The implementation process engages individuals from different hierarchical levels. Each hierarchical level gives its contribution by bringing in the information and experiences it possesses. Quality interaction between hierarchical levels should ensure a better formulation and implementation process (Hrebiniak, 2006; Mantere, 2008).

The research idea was that examining the attitudes of those implementing the strategy in their day-to-day business is necessary because only by combining a strategic and operational perspective can we gain more concrete and complete insights that would be of use to practitioners. Their experiences and attitudes reflect a more realistic picture of the strategy implementation process within an enterprise. Our research hypothesizes that employees from different hierarchical levels perceive key implementation factors differently because of the different intrinsic and extrinsic influencing factors, such as the degree of information possession, involvement in the formulation/ implementation process, accumulated job experience, etc. Although this research does not go into the description and analysis of the impact of individual intrinsic and extrinsic factors on employees’ perceptions of the strategy implementation process, we wanted to prove that it is necessary to include the perspectives of the various actors involved in the strategy implementation process. This is because it is rather difficult to expect that scientific research is able to develop useful guidance for practitioners if only one isolated opinion within the enterprise (usually top management) continues to be explored.

The implementation process in our research was evaluated using four implementation factors: People, Resources, Communication, Operational planning & control. Empirical findings show a statistically significant difference in the way respondents from different hierarchical levels assess factors Communication and Operational planning & control, while there are no statistical differences in assessing People and Resources. Although People (M = 3.55) and Resources (M = 3.59) are the lowest rated, the hierarchical levels are harmonious in expressing that there are not adequately allocated. Generally, our results show that top management rates the implementation of all four factors considerably higher than lower hierarchical levels.

Within the Communication factor, lower hierarchical levels mostly lament that their opinions and suggestions are not sufficiently respected, that the communication process is too slow, and that changes and innovations from the strategic point are not communicated to them in a timely way, which creates confusion and reduces the efficiency in coordinating operational tasks and introducing potential changes. In addition, from the analysis of the results, operatives point out that they receive too vague and unclear information, without adequate instructions on how to implement it concretely. Our conclusion is that the poor flow of information between hierarchical levels leads to reduced efficiency in coordinating the operative tasks. There is a need for a “strategy as practice” approach, which emphasizes the importance of the interaction between all hierarchical levels throughout the entire strategic management process by applying a bottom-up approach to decision-making and constantly developing the skills needed to cope quickly with ever-changing conditions. This approach contradicts the fact that top management is primarily in charge of strategy formulation while other levels are responsible for strategy implementation; within this approach, the strategy is adapted to meet the daily challenges and changing circumstances (Johnson et al., 2008). From our research, it emerges, as also noted before by others (e.g., Noble, 1999; Hrebiniak, 2006), that the non-integration of individuals potentially causes misunderstanding and is one of the key sources of problems that prolong and/or complicate the implementation process.

In the interpretation of the statistically significant difference in the evaluation of the Operational planning & control variable, we want to emphasize that, among all of the investigated aspects within this variable, the respondents from lower hierarchical levels rated the implementation dynamics as the worst. Strategy implementation generally lags, time-wise, behind scheduled plans. Moreover, lower hierarchical levels also emphasize that set budgets are often exceeded and that the work procedures are not clear. Operatives believe that the superiors do not take timely corrective actions when they notice that an obstacle has occurred in the course of the implementation. The explanation should clearly be sought in the interrelation with other key implementation factors.

CONCLUSION

The hypothesis has been only partially proven and the research results respond only partially to the research questions. The results of the empirical study show that hierarchical levels are not the only and the best grouping variable or perspective that could group different perspectives on the strategy implementation process. Some additional grouping variables or perspectives could be explored to realize the obstacles and suggest an improvement for strategy implementation. Further research should be directed towards the identification of those grouping variables of perspectives.

We also believe that it would be useful to approach the research topic through other research methods, bringing everything to a more qualitative research approach. Only in this way will it be possible to provide an in-depth explanation of what affects the perspective of each level and how the differences in the evaluation of the implementation process can contribute to the development of implementation models. Additionally, it should also be noted that, depending on the research subject, the respondents’ answers, and the respondents’ position, it can be weighted differently, thus ensuring more accurate reasoning. It is important to consider the extent of the respondents’ awareness and understanding of the issue under consideration, again depending on the research topic, his/her involvement in the particular situation, and specific research conditions to interpret his/her perspective correctly.

Furthermore, future research needs to be extended to the analysis of intrinsic and extrinsic factors that influence the respondents’ perspective in order to provide an in-depth explanation of what affects the perspective of each level and how the differences in the evaluation of the implementation process can contribute to the development of more concrete strategy implementation frameworks and guidelines. Research could be widened to include middle and small firms, and test the validity of the proposed model with different hierarchical levels on the different size of enterprises. Different research settings and control variables such as the same industry and strategy implementation could make a difference in the results.

Most of the current studies were performed in Anglo-Saxon countries and very rarely in the setting of Eastern European or transitional economies. Several examples of research on the issue of strategy implementation in the transitional economy were given, for instance, by Pučko and Čater (2008) and Radoš (2011). The field of strategy implementation in Eastern European economies is not sufficiently explored and the studies on this topic should certainly be intensified.

We need to highlight two difficulties we encountered during our research. Some respondents were not quite clear about their position in the hierarchical pyramid. Hierarchical positions are not always well defined and explained to lower hierarchical levels. In addition, we noticed that employees from lower hierarchical levels felt frustrated when answering some of the questions, which may be caused by a lack of understanding of the topic or their reluctance to express their views. Additionally, this proves that there is insufficient communication among different hierarchical levels and that lower levels are usually not familiar enough with the essential facts within the implementation process, which in turn, further contributes to their sense of guardedness and fear of expressing their attitude.

Acknowledgment

This article has been financed by the project of University of Rijeka under the title Challenges of Strategic Management Practice (ZP UNIRI 6/17).

References

Alexander, L. (1985). Successfully implementing strategic decision. Long Range Planning. 18(3), 91-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(85)90161-X

Al Ghamdi, S.M. (1998). Obstacles to successful implementation of strategic decisions: The British experience. European Business Review, 98(6), 322-327. https://doi.org/10.1108/09555349810241590

Allio, M.K. (2005). A short, practical guide to implementing strategy. Journal of Business Strategy, 26(4), 12-21. https://doi 0.1108/02356660510608512

Anchor, J.R., Aldehayyat, J.S., & Jehad, S. (2012). Strategy implementation in Jordanian hotels. Retrieved from http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/16402

Asmuss, B. (2018). Strategy as practice. The International Encyclopedia of Strategic Communication. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119010722.iesc0185

Beer, M., & Eisenstat, R. (1996). Developing an organization capable of strategy implementation and learning. Human Relations, 49, 597–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679604900504

Beer, M., Eisenstat, R. (2000). The silent killers of strategy implementation and learning. Sloan Management Review, 41(4), 29-40.

Behery, M. (2016). A new look at transformational leadership and organizational identification: A mediation effect of followership style in a non-western context. Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship, 21(2), 70–94. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.3709.2016.ap.00006

Blahová, M., & Knápková, A. (2011). Effective strategic action: From formulation to implementation. International Conference on Economics, Business and Management, 2, 61-65. Retrieved from http://ipedr.com/vol2/13-P00027.pdf

Bouckenooghe, D. (2012). The role of organizational politics, contextual resources, and formal communication on change recipients’ commitment to change: A multilevel study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 21(4), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2011.591573

Brinkschröder, N. (2014). Strategy Implementation: Key factors, challenges and solutions, [Master degree dissertation, Wilmington University]. Retrieved from https://essay.utwente.nl/66188/1/brinkschroeder_BA_MB.pdf

Chowdhury, N. (2016). Middle managers role in strategy implementation. Leadership & Management. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/NafisChowdhury007/assignment-on-middle-manager

Cândido, C.J.F., & Santos, S.P. (2019). Implementation obstacles and strategy implementation failure. Baltic Journal of Management, 14(1), 39-57. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-11-2017-0350

Cobbold, I., & Lawrie, G. (2001). Why do only one third of UK companies achieve strategic success? Times 1000. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/06b1/f81bdc1736c694ff46d0ce05e5d33f7d117b.pdf

Darkow, I.E. (2015). The involvement of middle management in strategy development -Development and implementation of a foresight-based approach. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 101, 10-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2013.12.002

DeLisi, P.S. (2001). Strategy execution: An oxymoron or a powerful formula for corporate success. Retrieved from http://www.org-synergies.com/Strategy%20Execution%20Paper3.pdf

Dooley, R.S., Fryxell, G.E., & Judge, W.Q. (2000). Belaboring the non-so-obvious: Consensus, commitment, and strategy implementation speed and success. Journal of Management, 26(6), 1237-1257. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600609

Engert, S., & Baumgartner, R.J. (2014). Corporate sustainability strategy – bridging the gap between formulation and implementation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 113, 822-834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.11.094

Ewenstein, B., Smith, W., & Sologar, A. (2015). Changing change management [Supplemental material]. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/leadership/changing-change-management

Floyd, S.W., & Wooldridge, B. (1992). Managing strategic consensus: The foundation of effective implementation. The Executive. 6(4), 27-39. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1992.4274459

Floyd, S. W., & Lane, P. J. (2000). Strategizing throughout the organization: Managing role conflict in strategic renewal. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 154-177. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.2791608

Gibson, C.B., Birkinshawb, J., Sumpeter, D.M., & Ambosd, T. (2019). The hierarchical erosion effect: A new perspective on perceptual differences and business performance. Journal of Management Studies, 56(8), 1713-1747. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12443

Grönroos, C. (1995). Relationship marketing: The strategy continuum. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23(4), 252-254. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02893863

Hassan, A.A. (2016). Effects of dynamic capabilities on strategy implementation in the dairy industry in Kenya. International Academic Journal of Human Resource and Business Administration. 2(2), 64-105.

Harrison, D. (2017). Over 70% of executives surveyed agree: Strategic planning efforts lack a systematic approach. Center for simplified strategic planning Inc. Retrieved from https://www.cssp.com/over-70-of-executives-surveyed-agree-strategic-planning-efforts-lack-a-systematic-approach/

Heathfield, S.M. (2019). How to reduce employee resistance to change. Retrieved from https://www.thebalancecareers.com/how-to-reduce-employee-resistance-to-change-1918992

Heracleous, L. (2003). Strategy and Organization, Realizing Strategic Management. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hrebiniak, L.G. (2005). Making Strategy Work: Leading Effective Execution and Change. New York: Wharton School Publishing.

Hrebiniak, L.G. (2006). Obstacles to effective strategy implementation. Organizational Dynamics, 35(1), 12-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2005.12.001

Huey, J. (1994). The new post-heroic leadership. Fortune, 21, 42-50.

Ikävalko, H., & Aaltonen, P. (2001). Middle managers’ role in strategy implementation – Middle managers view (Ph.D. Thesis, Helsinki University of Technology Industrial Engineering and Management, Helsinki, Finland).

Johansson, E.W., & Svensson, J. (2017). Implementing strategy? Don’t forget the middle managers: Strategy implementation from a middle management perspective. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/12ab/ff89231a1603727a52d0652ec1a0a225c096.pdf?_ga=2.173781163.981304331.1590593197-872826786.1577728146

Johnson, G. et al. (2008). Exploring Corporate Strategy (8th ed.). London: Pearson.

Kalali, N.S., Anvari, M.R.A., Pourezzat, A.A., & Dastjerdi, D.K. (2011). Why does strategic plans implementation fail? A study in the health service sector of Iran. African Journal of Business Management, 5(23), 9831-9837. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM11.430

Klettner, A., Clarke, T., & Boersma, M., (2014). The governance of corporate sustainability: Empirical insights into the development, leadership and implementation of responsible business strategy. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(1), 145-165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1750-y

Koseoglu, M.A., Barca, M., Karayormuk, K., & Edas, M. (2009). A study on the causes of strategies failing to success. Journal of Global Strategic Management, 6, 71-91. https://doi.org/10.20460/JGSM.2009318462

Kownatzki, M., Walter, J., Floyd, S.W., & Lechneret, C. (2013). Corporate control and the speed of SBU–level decision making. Academy of Management Journal, 56(5), 1295–1324. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0804

Li. Y., Guohui, S., & Eppler, M.J. (2008). Making strategy work: A literature review on the factors influencing strategy implementation. Retrieved from http://www.knowledge-communication.org/pdf/making-strategy-work.pdf

Mankins, M.C. (2005). Turning great strategy into great performance. Harvard Business Review, 8(7), 64-72.

Mantere, S. (2008). Role expectations and middle manager strategic agency. Journal of Management Studies, 45(2), 294-316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00744.x

Miller, K (2020). A manager’s guide to successful strategy implementation. Business Insights, Harvard Business School Online. Retrieved from https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/strategy-implementation-for-managers

Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Croatia. (2016). Industrijska strategija Republike Hrvatske 2014–2020. Retrieved from https://vlada.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/2016/Sjednice/2014/182%20sjednica%20Vlade/182%20-%201.pdf

Noble, C.H. (1999). The eclectic roots of strategy implementation research. Journal of Business Research, 45(2), 119-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00231-2

Noble, C.H. (1999a). Building the strategy implementation network. Business Horizons, 42(6), 19-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0007-6813(99)80034-2

Nutt, P.C. (1986). Tactics of implementation. Academy of Management Journal, 29(2), 230-261.

Okumus, F. (2001). Toward a strategy implementation framework. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 13(7), 327-338. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110110403712

Okumus, F. (2003). A framework to implement strategies in organizations. Management Decision, 41(9), 871-882. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740310499555

O’Regan, N., & Ghobadian, A. (2007). Formal strategic planning: Annual raindance or wheel of success?. Strategic Change, 16(1-2), 11-22. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.777

Pereverzieva, A. (2019). A methodical approach to the assessment of human resources` interactions. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 15(1), 171-204. https://doi.org/10.7341/20191517

Pučko D., & Čater T. (2008.). A holistic strategy implementation model based on the experiences of Slovenian companies. Economic and Business Review for Central and South-Eastern Europe, 10(4), 307-325.

Radoš, T. (2006.). Ključni faktori procesa implementacije strategije u hrvatskim poduzećima. Ekonomska Misao i Praksa. 19(2), 163-183.

Radoš, T. (2011.). Problemi procesa implementacije strategije u hrvatskim poduzećima. Ekonomski Vjesnik, 24(1), 137-154.

Ramadan, M.A. (2015). The impact of strategy implementation drivers on projects effectiveness in non-governmental organizations. International Journal of Academic Research in Management, 4(2), 35-47.

Rapert, M.I., Lynch, D., & Suter, T. (1996). Enhancing functional and organizational performance via strategic consensus and commitment, Journal of Strategic Marketing, 55(4), 301-310. https://doi.org/10.1080/09652549600000004

Sali, A., & Doll, Y. (2013). A middle management perspective on strategy implementation. International Journal of Business and Management, 8(22), 32-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v8n22p32

Schaap, J.I. (2006). Toward strategy implementation success: an empirical study of the role of senior-level leaders in the Nevada gaming industry. UNLV Gaming Research & Review Journal, 10(2), 13-37.

Schaap, I. (2012). Strategy implementations - Can organizations attain outstanding Performance?. Strategic Management Review, 6(1), 98–121.

Shah, A.M. (2005). The foundations of successful strategy implementation-overcoming the obstacles. Global Business Review, 6(2), 293-302. https://doi.org/10.1177/097215090500600208

Shimizu, K. (2017). Senders’ bias: How can top managers’ communication improve or not improve strategy implementation?. International Journal of Business Communication, 54(1), 52-69. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488416675449

Simons, R. (2013). The entrepreneurial gap: How managers adjust span of accountability and span of control to implement business strategy. Harvard Business School Accounting & Management Unit Working Paper. Retrieved from https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2280355

Tawse, A., Patrick, V. M., & Vera, D. (2019). Crossing the chasm: Leadership nudges to help transition from strategy formulation to strategy implementation. Business Horizons, 62(2), 249-257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2018.09.005

Tiemersma, E.M. (2015). Coping with strategy implementation: A challenge (Master of Business Administration, University of Twente, Netherlands). Retrieved from https://essay.utwente.nl/67742/1/Tiemersma_MA_MB.pdf

Tovstiga, G. (2010). Strategy in Practice. Cornwell, UK: Wiley Publication.

Verweire, K. (2018). The challenges of implementing strategy. Advances in Project Management Series. PM World Journal, 7(5), 1-12.

Wheelen, T.L., & Hunger, J.D. (2010). Concepts in Strategic Management and Business Policy. Prentice-Hall, New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc..

Whittington, R. (1996). Strategy as practice. Long Range Planning, 29(5), 731- 735.

Wolczek, P. (2014). Strategy formalization in the practice of Polish companies. Universal Journal of Management, 2(1), 9-18. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujm.2014.020102

Zafar, F., Butt, A., & Afzal, B. (2014). Strategic management: Managing change by employee involvement. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research, 13(1), 205-217.

Abstrakt

Cel: Mimo, że proces wdrożenia angażuje pracowników z różnych szczebli hierarchicznych, wcześniejsze badania dotyczące tematu wdrożenia koncentrowały się głównie na perspektywie najwyższego kierownictwa, pomijając perspektywę niższych szczebli hierarchicznych. Uważamy, że z powodu wielu wewnętrznych i zewnętrznych wpływów pracownicy na różnych poziomach hierarchii inaczej postrzegają sposób realizacji procesu wdrożeniowego. Biorąc pod uwagę podstawową rolę niższych szczebli hierarchicznych w procesie wdrażania, zdecydowaliśmy się włączyć do naszych badań niższe szczeble kierownictwa i pracowników. Metodyka: Proces wdrożenia w naszym badaniu został oceniony na podstawie czterech czynników: 1) Ludzie, 2) Alokacja zasobów, 3) Komunikacja, 4) Planowanie operacyjne i kontrola. Wysłaliśmy kwestionariusz do wszystkich dużych chorwackich przedsiębiorstw (396) i zebraliśmy 208 kwestionariuszy z 78 przedsiębiorstw. Wyniki: Wyniki badań potwierdzają, że ocena kluczowych czynników wdrażania różni się znacząco między poziomami hierarchii w dwóch z czterech zidentyfikowanych czynników: 1) Komunikacja oraz 2) Planowanie operacyjne i kontrola. Menedżerowie i operatorzy pierwszej linii najczęściej uważają instrukcje wdrożenia strategii za zbyt niejasne, ich sugestie nie są brane pod uwagę, komunikacja generalnie jest za wolna, co powoduje zamieszanie i zmniejsza efektywność w koordynowaniu zadań operacyjnych i wprowadzaniu potencjalnych zmian. Implikacje dla teorii i praktyki: Chociaż udowodniliśmy statystycznie różne postrzeganie dwóch z czterech czynników procesu wdrożenia, przyczyniliśmy się do wskazania, że ten strumień badań, z wieloma czynnikami i wieloma respondentami z różnych poziomów hierarchicznych, powinien być wzięty pod uwagę. Najwyżsi menedżerowie powinni uwzględnić informacje zwrotne od menedżerów z niższych szczebli hierarchicznych, aby uchwycić pułapki związane z wdrażaniem strategii. Badanie to zwraca uwagę na problemy operacyjne, które mogą wystąpić, takie jak niejasna lub powolna komunikacja, rozbieżności budżetowe, nieodpowiednie określenie harmonogramu działań i ich dynamiki oraz sposoby mierzenia wyników podczas wdrażania strategii. Wierzymy, że wyniki badań są korzystne dla naukowców i konsultantów przy tworzeniu programów dydaktycznych i szkoleniowych dla przyszłych menedżerów z zakresu wdrażania strategii. Oryginalność i wartość: Na podstawie analizy przeglądu literatury i wyników badań opracowujemy nowy model wdrożenia wraz z kwestionariuszem do analizy sposobu, w jaki pracownicy na różnych poziomach hierarchii postrzegają proces wdrożenia.

Słowa kluczowe: proces wdrożenia strategii, kluczowe czynniki wdrożenia, poziomy hierarchiczne, perspektywy pracowników na proces wdrażania strategii, duże chorwackie przedsiębiorstwa.

Biographical notes

Valentina Ivančić worked first as a young researcher and later as a Professor Assistant at the Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Rijeka (Croatia) until 2018. She held seminar classes on these subjects: Strategic Management, Quality Management, Market Research, and Promotion. She finished the training program for Internal Auditor ISO 9001:2015 and several seminars on Applied Statistics. In 2015 she was awarded her Ph.D. in the field of Strategic Management (topic: strategy implementation). In the last decade, she has participated in the preparation and implementation of several scientific projects, while in the last year, as a consultant, she has been more involved in the improvement of the implementation process of certain Croatian enterprises.

Lara Jelenc is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Rijeka, Croatia. Her degree is from the Faculty of Economics and Business in Ljubljana, Slovenia. She was awarded a scholarship under the Junior Development Development Program in the USA, at the George Washington University. She serves on the editorial board of Qlife, a Croatian journal about science and art of leadership. She completed her training in executive coaching, strategic thinking, NLPt and for Lead Auditor ISO 9001:2008. She is serving as a consultant in HE and NGO sectors and volunteers in local community positions. Her interests are in strategic thinking and its develoment among managers and entrepreneurs.

Ivan Mencer is a retired Professor at the Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Rijeka, teaching Strategic Management, Quality Management, Market Research, and Promotion. Between 2000 and 2004, he served as Dean at the Faculty of Economics, University of Rijeka. Mencer was the Chair of Department of Economics and Maritime Shipping Organization at the Faculty of Maritime Studies University of Rijeka (from 1987 to 1991), and attended training in the quality management area for Internal Audit ISO 9000:1994, Lead Audit ISO 9000:1994, and Lead Audit 9001:2000 (2001). He was the Chief Editor of four issues of Proceedings of Faculty of Economics University of Rijeka (1994-1996) and a member of editorial board of the international journal „Ekonomski pregled” (from 2001 until 2016). In 2009 he started to serve as the director of the first generation of the MBA study “Business Performance Management” that offers an integrated program of management and psychology classes.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Citation

Ivančić, V., Jelenc, L., & Mencer, I. (2021). The strategy implementation process as perceived by different hierarchical levels: The experience of large Croatian enterprises. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 17(2), 99-124. https://doi.org/10.7341/20211724