Chao-Tung Liang, Assistant Professor, Department of Cultural Creativity and Digital Media Design, Lunghwa University of Science and Technology, New Taipei, Taiwan. E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Chaoyun Liang, Professor, Department of Bio-Industry Communication and Development, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Chaoyun Liang, Department of BioIndustry Communication and Development, National Taiwan University, No. 1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Road, Taipei, 10617, Taiwan. E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Abstract

Numerous technopreneurs start their ventures at college age, but the entrepreneurship of computer and electrical engineering (CEE) students remains under-studied. This study analysed both the combined and interactive effects of psychological factors on the entrepreneurial intentions of CEE students. In this study, entrepreneurial intention comprised two dimensions, conviction and preparation. Regarding the direct effects, the results indicated that self-efficacy affected entrepreneurial conviction the most, followed by negative emotion, intrinsic motivation, and metacognition. Negative emotion affected entrepreneurial preparation the most, followed by self-efficacy and positive emotion. The results also revealed several crucial interactive effects resulting from psychological factors. An increase in cognitive load increased the entrepreneurial intention of students exhibiting high intrinsic motivation and reduced the intention of students exhibiting low intrinsic motivation. An increase in metacognition increased the entrepreneurial conviction of students exhibiting either high or low intrinsic motivation. An increase in positive emotion reduced the entrepreneurial intention of students exhibiting high negative emotion and increased the intention of students exhibiting low negative emotion. An increase in self-efficacy increased the entrepreneurial intention of students exhibiting either high or low negative emotion.

Keywords: computer and electrical engineering (CEE), entrepreneurial intention, interactive effects, psychological factors, university students.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship is a primary source of economic growth that creates business opportunities and reduces unemployment (Szirmai, Naude, & Goedhuys, 2011). Specifically, information technology sectors have been amongst the major drivers of economic growth in numerous countries over the past decades. Among the emerging concerns of technology sector management, technopreneurship has become a central one (Klincewicz, 2012), particularly in developing countries (Szirmai et al., 2011).

Taiwan’s computer and electrical engineering (CEE) industry has been ranked high worldwide. A high percentage of worldwide CEE products are manufactured by Taiwanese original equipment manufacturers, thus influencing the choice of programmes of university students in Taiwan. In the past 10 years, CEE related programmes (i.e., electrical engineering, electronic engineering, computer technology, and information management) in universities have been listed amongst the top 10 choices of high school students (Ministry of Education, 2015). Most students graduating from CEE programmes choose large CEE firms in science parks to work, but increasing numbers of them have undertaken ventures on the basis of their innovative ideas and techniques in CEE. Entrepreneurship has become a widely discussed concept and an action of choice for numerous CEE graduates.

Although numerous CEE entrepreneurs start their ventures at college age, student entrepreneurship remains under-studied in business research (Liang, Chia, & Liang, 2015). Particularly, research on CEE entrepreneurial intention and behaviour has been ignored in technology education disciplines (Chen, 2013). Scholars indicated that entrepreneurial intention and behaviour involves numerous psychological factors that should be intensively studied (Leon, Gorgievski, & Lukes, 2008; Obschonka, Schmitt-Rodermund, Silbereisen, Gosling, & Potter, 2013). These psychological factors include cognition, motivation, emotion, and self-efficacy (Carsrud & Brännback, 2012; Markman, Balkin, & Baron, 2002; Ooi & Ahmad, 2012; Welpe, Spörrle, Grichnik, Michl, & Audretsch, 2012). However, few studies have empirically examined how these psychological factors interactively influence the entrepreneurial intention amongst CEE students.

In keeping with these findings and to fill the research gap, the present study used college students with CEE majors to analyse the integrated effects of psychological factors on entrepreneurial intention and test the interactive effects resulting from these psychological factors. We focused on the psychological factors intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, positive emotion, negative emotion, cognitive load, metacognition, and self-efficacy. The assessment of entrepreneurial intention was based on Liñán and Chen (2009) and Lans, Gulikers, and Batterink (2010). The measurements of psychological factors were adopted from several international scales (Chen, Gully, & Eden, 2001; Harter, 1981; Hsu, Liang, & Chang, 2013; Paas, & van Merriënboer, 1994; Schraw & Dennison, 1994; Tuccitto, Giacobbi, & Leite, 2010).

Entrepreneurial intention

Thompson (2009) defined entrepreneurial intention as “a self-acknowledged conviction by a person that they intend to set up a new business venture and consciously plan to do so at some point in the future” (p. 676). Previous studies have indicated that entrepreneurial intention is a strong predictor of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1991; Bird, 1988; Covin & Slevin, 1989). Pittaway and Cope (2007) suggested that more studies on entrepreneurial intention should be linked to employability in small and medium enterprises to provide a justification that is more than merely economical. Universities have been regarded as a source of technological development that is useful to entrepreneurial activity (Shane, 2004). The present study focused on entrepreneurial intention, because intention towards purposive behaviour can be a crucial antecedent to entrepreneurial behaviour.

Cooper and Dunkelberg (1986) indicated that various paths to achieving business ownership are related to the background characteristics, motivations, attitudes, and employment history of owner-managers, as well as the support they receive and the processes they employ to start a new business. Cooper and Dunkelberg reported that entrepreneurs who establish firms differ considerably from those who are promoted or hired. Moreover, those who inherit or purchase a firm fall between these two extremes. On the basis of this observation, Lans et al. (2010) defined three types of intention to create a business; classical entrepreneurial intention (i.e., the intention to establish a business), alternative entrepreneurial intention (i.e., the intention to continue operating an inherited or acquired firm), and intrapreneurial intention (i.e., the intention to be an intrapreneur or corporate entrepreneur). These three types of intention suggest that learning goals and professional needs differ amongst entrepreneurs. In the current study, entrepreneurial intention was measured according to Liñán and Chen (2009) and Lans et al. (2010).

Prodan and Drnovsek (2010) claimed that there are knowledge gaps regarding the specific determinants and processes that characterise the emergence of academics’ entrepreneurial intentions that lead them to establish spin-off companies. Prodan and Drnovsek proposed that psychological and entrepreneurial research on intentionality should be devoted to this topic. Previous studies have indicated that the entrepreneurial intentions of undergraduate students in business and engineering majors are influenced by their family members, academics, attending courses on entrepreneurship, gender differences, and personality traits (Chen & Chen, 2015; Gerba, 2012; Zain, Akram, & Ghani, 2010). Murah and Abdullah (2012) studied computer science students and found that their entrepreneurial intentions were influenced by entrepreneurial experience in childhood, family background, personality type, and future plans. Kaltenecker and Hörndlein (2013) identified attitude as the main driver for information systems students, and discovering business ideas was the most influential factor for computer science students. The opportunity for self-fulfilment and the prospect of a high monetary reward were identified as the crucial drivers for these students. The results of aforementioned studies indicate that various psychological factors have a profound impact on student intention of entrepreneurship.

psychological factors

Leon et al. (2008) indicated that prior research on entrepreneurial intentions has long been associated with the field of psychology. The critical psychological factors may include motivation, cognition, emotion, and self-efficacy. Both extrinsic and intrinsic motivation affect a person’s future actions and provide energy, direction, and persistence for entrepreneurial intention (Dej, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Extrinsic motivation refers to a person’s internal desire, which is driven by their interest or enjoyment in performing a task, and includes security, wealth, status, power (Vesalainen & Pihkala, 1999), group setting, organisational characteristics (Choi, Price, & Vinokur, 2003), social norms (Ajzen, 1991), and cultural context (Liñán & Chen, 2009). Extrinsic motivation can transform into intrinsic motivation in supportive environments (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Intrinsic motivation refers to that from external pressures or rewards, and includes attitude, behavioural control (Ajzen, 1991), personal attractiveness, experience, involvement, and engagement (Kamau-Maina, 2008). Previous research has particularly suggested that the closer to an entrepreneurial career the decision making occurs, the more personal intrinsic motivation is involved (Carsrud & Brännback, 2012; Vesalainen & Pihkala, 1999). Therefore, we proposed the first following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation predict entrepreneurial intention.

Previous studies have determined that positive emotions (emotional responses that are modelled to dictate positive affection, including excitement, happiness, joy, and satisfaction) and negative emotions (unpleasant or unhappy emotions that express a negative affection towards an event or person, including fear of failure, anger, loneliness, mental strain, and grief) influence people’s judgment, memory recall, and deductive and inductive reasoning (George, 2000), as well as the decision to engage in self-employment (Patzelt & Shepherd, 2011; Welpe et al., 2012). Numerous scholars have confirmed that entrepreneurs’ emotions, which are antecedent to, concurrent with, and a consequence of the entrepreneurial process, are likely to affect the recognition, creation, evaluation, reformulation, and exploitation of business opportunities (Cardon, Foo, Shepherd, & Wiklund, 2012; Podoynitsyna, Van der Bij, & Song, 2012); hence, emotional intelligence has become a crucial factor in cultivating entrepreneurial students (Zakarevičius & Župerka, 2010). We thus proposed the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Both positive and negative emotions predict entrepreneurial intention.

Furthermore, previous studies have emphasised the effects of cognitive resources on business start-ups (Haynie, Shepherd, & Patzelt, 2012; Van Gelderen, 2009). Successful entrepreneurs must be capable of making appropriate choices to avoid cognitive overload resulting from novelty, change, uncertainty, and complexity (Van Gelderen, 2009). Cognitive load here refers to the overall mental activity imposed on a person’s working memory at a particular time. Sánchez (2012) concluded that people intending to establish a business apply cognitive scripts that allow them to process information and perceive the advantages of starting a business despite adverse market conditions. In addition, Haynie, Shepherd, Mosakowski, and Eagly (2010) suggested that metacognitive abilities are core characteristics of entrepreneurial cognition because they enable entrepreneurs to think beyond existing knowledge and promote adaptable cognition in novel decision contexts. Metacognition here refers to the processes that allow people to consider their cognitive abilities. Urban (2012) concluded that potential entrepreneurs consciously consider the possibility of starting a new business, and that their entrepreneurial intentions are the result of metacognitive processes. Therefore, we proposed the third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Both the cognitive load and metacognition predict entrepreneurial intention.

In addition to expected outcomes and social influences, self-efficacy has been proven to be the most crucial psychological factor affecting the entrepreneurial intentions of students (Chen, 2013). Self-efficacy refers to a person’s belief regarding their ability to succeed in specific situations. People with high self-efficacy typically perceive themselves as capable of affecting change and performing actions that are necessary to resolve problems (Bandura, 2000). Self-efficacy has frequently been applied to explain entrepreneurship as a series of definitive thought processes in which entrepreneurs perceive their abilities to be superior to those of other people, and hence they reason that their abilities can be applied to achieve favourable outcomes (Neck, Neck, Manz & Godwin, 1999; Zhao, Seibert, & Hills, 2005). Markman et al. (2002) determined that general self-efficacy can be applied to entrepreneurship, and it has been used to link inventors with people who establish new ventures. We thus proposed the fourth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Self-efficacy predicts entrepreneurial intention.

Regarding the interactive effects amongst these psychological factors, previous research has indicated that human motivation affects cognitive resources and vice versa (Liang, Hsu, & Chang, 2013). Positive and negative emotions affect each other (Waugh, 2013), and self-efficacy and negative emotion also exhibit a mutual influence (Lightsey, Maxwell, Nash, Rarey, & McKinney, 2011). Therefore, we proposed the following four hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5: Intrinsic motivation and cognitive load interact in predicting entrepreneurial intention.

Hypothesis 6: Intrinsic motivation and metacognition interact in predicting entrepreneurial intention.

Hypothesis 7: Negative and positive emotions interact in predicting entrepreneurial intention.

Hypothesis 8: Negative emotion and self-efficacy interact in predicting entrepreneurial intention.

Method

This study examined the effects of psychological factors on the entrepreneurial intention of CEE students and tested the interactive effects resulting from these psychological factors. A 9-item entrepreneurial intention scale (EIS) was adopted from Wang, Peng, and Liang (2014), which was based on Liñán and Chen (2009) and Lans et al. (2010). In addition, we adopted a 37-item psychological variable scale (PVS; Wang et al., 2014), which was based on several international scales (Chen et al., 2001; Harter, 1981; Hsu et al., 2013; Paas & van Merriënboer, 1994; Schraw & Dennison, 1994; Tuccitto et al., 2010). These two scales were scored on a 6-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The details regarding the reliability and validity of the survey tools are reported in the following section.

We recruited 815 CEE students from three universities in Taiwan and divided this sample into two groups. The first group consisted of 305 students and was used to confirm the factor structures of the scales. The second group comprised 510 students and was used to test the hypotheses and build a structural model. In the first group, most of them were men (65.57%); 23.61% were freshmen, 25.57% were sophomores, 26.89% were juniors, and 23.93% were seniors. The participants were between 18 and 25 years of age (M = 20.54, SD = 0.76). In the second group, most of them were men (64.12%); 22.16% were freshmen, 23.73% were sophomores, 26.67% were juniors, and 27.44% were seniors. The participants were between 18 and 27 years of age (M = 20.96, SD = 0.87).

The research team discussed the scale items with instructors in the target CEE programmes before conducting the survey. A paper questionnaire was administered by trained graduate assistants, either during or immediately after regular class time. Thus, any problems that participants faced when answering the questions could be directly resolved. Identical survey procedures were used to administer the survey in each target programme in the absence of class instructors to decrease social desirability bias (i.e., students may attempt to project a positive self-image to adapt to social norms whilst answering the questions if class instructors are present). Moreover, participation by the students was voluntary, confidential, and anonymous.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with a maximum likelihood estimator was performed using LISREL 8.80 to test the factorial validity of the scales used in this study. We adopted indicators recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999) and Tabachnick and Fidell (2001) to assess the goodness of fit of the model. Regarding the EIS, the two-factor solution yielded a good fit (χ2 = 223.12, df = 26, p < .005, RMSEA = .080, SRMR = .067, CFI = .97, NFI = .96, TLI = .96). The seven-factor solution of the PVS yielded a good fit (χ2 = 1702.692, df = 608, p < .005, RMSEA = .078, SRMR = .072, CFI = .94, NFI = .91, TLI = .93). Table 1 shows the factor loadings and composite reliability result.

According to our data, the analysis of the composite reliability estimates demonstrated that both PVS and EIS exhibited strong internal consistency. For group one (n = 305), construct validity was determined on the basis of convergent and discriminant validity. The convergent validity of each factor was tested by assessing the standardised factor loadings (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010). Discriminant validity was assessed by calculating the confidence intervals of the interfactor correlation estimates, denoted as φ (Bagozzi & Yi, 1998). The results indicated that both convergent and discriminant validity were assured.

| Variable | psychological Variable scale | Entrepreneurial Intention Scale | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item/ Factor | Intrinsic motivation | Extrinsic motivation | Positive emotion | emotion Negative emotion | Cognitive load | Meta- -cognition | Self- -efficacy | Conviction | Preparation |

| 1 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 0.85 | 0.90 |

| 2 | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.90 | 0.91 |

| 3 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 0.83 | 0.63 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.68 |

| 4 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.76 | ||

| 5 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.73 | ||||

| 6 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.72 | ||||||

| 7 | |||||||||

| 8 | 0.67 | 0.81 | |||||||

| 0.65 | 0.74 | ||||||||

| Composite reliability | 0.827 | 0.635 | 0.895 | 0.863 | 0.820 | 0.893 | 0.915 | 0.909 | 0.875 |

Interactive effects

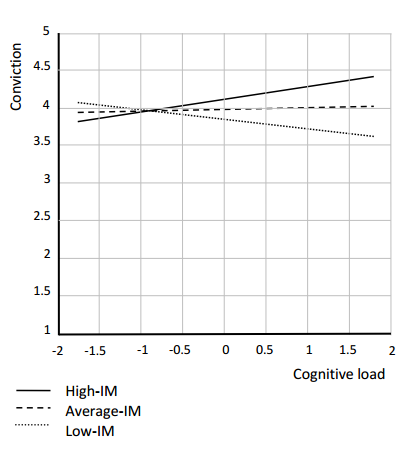

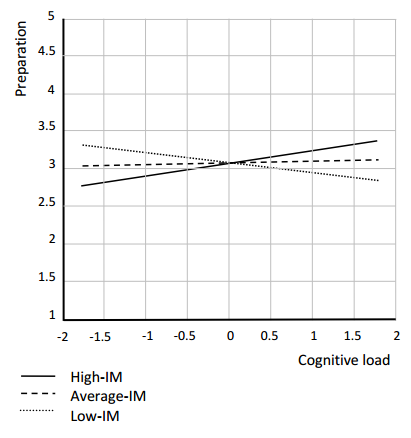

For group two, the hypotheses of interactive effects were tested using LISREL 8.80. Simple slopes and regression lines for each level of the first moderator (intrinsic motivation) were calculated to further examine the form of the interaction for interpreting the interactive effects. The results revealed that the entrepreneurial conviction of CEE students with high intrinsic motivation (high-IM, one standard deviation above the mean) was lower than that of those with low intrinsic motivation (low-IM, one standard deviation below the mean) at low levels of cognitive load. However, at high levels of cognitive load, the entrepreneurial conviction of the high-IM students largely exceeded that of the low-IM students (Figure 1). Regarding the interactive effect resulting from intrinsic motivation and cognitive load on entrepreneurial preparation, the pattern was similar (Figure 2). Therefore, Hypothesis 5 was supported. The interactive effect on entrepreneurial conviction was higher than that on entrepreneurial preparation.

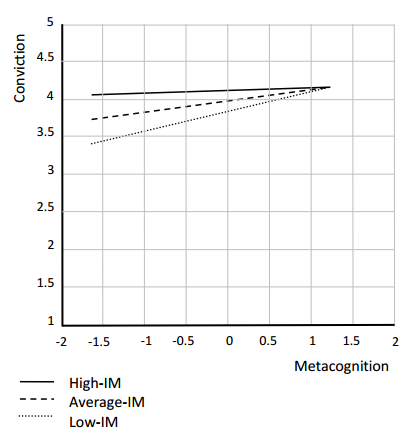

In addition, the results showed that the entrepreneurial conviction of the high-IM students was higher than that of the low-IM students when metacognition was low. However, at high levels of metacognition, the entrepreneurial conviction of the low-IM students approximated the same level of the high-IM students (Figure 3). The entrepreneurial conviction of the high-IM students appeared stable regardless of the level of their metacognition. The interactive effect resulting from intrinsic motivation and metacognition on entrepreneurial preparation was nonsignificant. Therefore, Hypothesis 6 was partially supported.

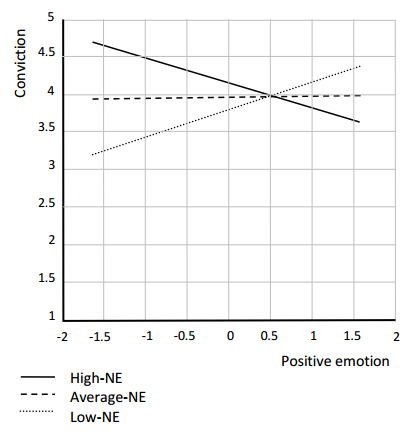

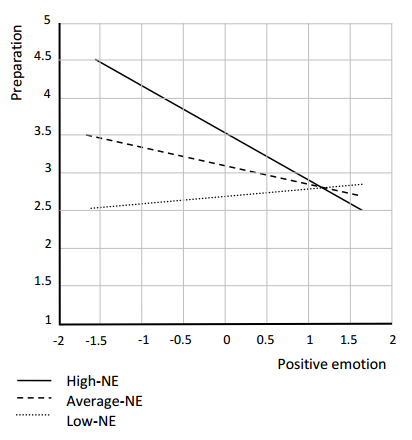

Simple slopes and regression lines for each level of the second moderator (negative emotion) were calculated to further examine the interactive effects. The results showed that the entrepreneurial conviction of CEE students with low negative emotion (high-NE, one standard deviation above the mean) was lower than that of those with high negative emotion (low-NE, one standard deviation below the mean) at low levels of positive emotion. However, at high levels of positive emotion, the entrepreneurial conviction of the low-NE students was higher than that of the high-NE students (Figure 4). The levels of entrepreneurial conviction of middle-NE students were stable regardless of whether the levels of positive emotion changed. Regarding the interactive effect resulting from negative and positive emotion on entrepreneurial preparation, the pattern was similar (Figure 5). The levels of entrepreneurial preparation of middle-NE students decreased in response to increased levels of positive emotion. Therefore, Hypothesis 7 was supported.

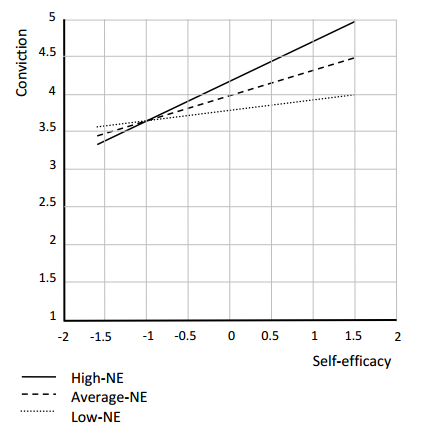

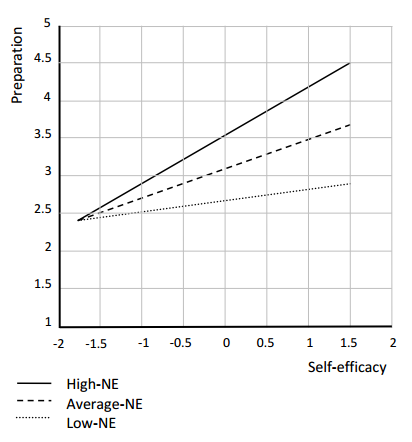

The results showed that the entrepreneurial conviction of the high-NE students was lower than that of the low-NE students when self-efficacy was low. However, at high levels of self-efficacy, the entrepreneurial conviction of the high-NE students was considerably higher than that of the low-NE students (Figure 6). In addition, the levels of entrepreneurial preparation of both high-NE and low-NE students were the same when self-efficacy was low. At high levels of self-efficacy, the entrepreneurial preparation of the high-NE students was considerably higher than that of the low-NE students (Figure 7). Therefore, Hypothesis 8 was supported. The interactive effect on entrepreneurial conviction was higher than that on entrepreneurial preparation.

Structural model

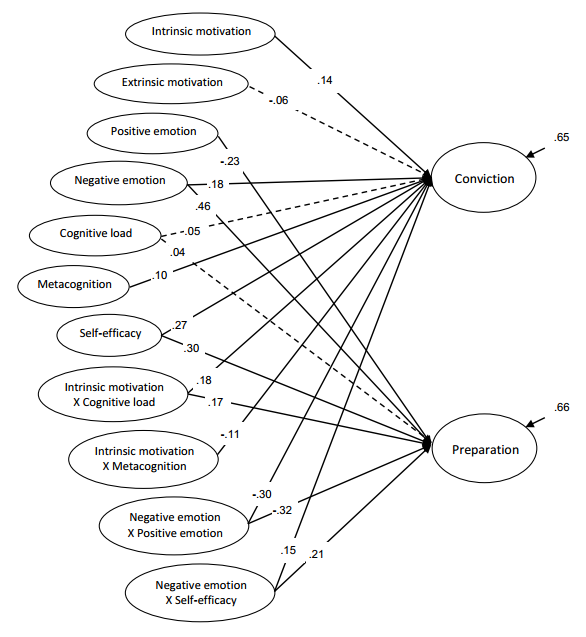

The hypotheses were tested using LISREL and by performing structural equation modelling with maximum likelihood estimation. The results showed that the model fit was adequate (χ2 = 5332.29, df = 1994, p < .005, RMSEA = .057, SRMR = .055, CFI = .94, NFI = .91, TLI = .94). The results enabled explaining a substantial level of variance for entrepreneurial conviction (R2 = .35), and entrepreneurial preparation (R2 = .34). Figure 8 depicts the structural model. The solid lines indicate a significant effect, whereas the dotted lines indicate a nonsignificant effect. Table 2 lists the correlations amongst the latent independent variables.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Intrinsic motivation | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2 | Extrinsic motivation | .18 | 1 | |||||||||

| 3 | Positive emotion | .60 | .45 | 1 | ||||||||

| 4 | Negative emotion | .23 | .11 | .06 | 1 | |||||||

| 5 | Cognitive load | .02 | .32 | .15 | .27 | 1 | ||||||

| 6 | Metacognition | .71 | .21 | .50 | .29 | .12 | 1 | |||||

| 7 | Self-efficacy | .73 | .18 | .55 | .30 | .09 | .74 | 1 | ||||

| 8 | Intrinsic motivation x Cognitive load | .12 | .10 | .00 | .20 | .21 | .11 | .06 | 1 | |||

| 9 | Intrinsic motivation x Metacognition | .07 | -.01 | .14 | .02 | .10 | .13 | .09 | -.02 | 1 | ||

| 10 | Negative emotion x Positive emotion | .08 | -.01 | -.09 | .54 | .06 | .13 | .03 | .25 | .07 | 1 | |

| 11 | Negative emotion x Self-efficacy | .04 | .14 | .02 | .33 | .14 | .06 | .02 | .17 | .25 | .57 | 1 |

| Note: *p < .05. | ||||||||||||

According to the data, intrinsic motivation positively predicted entrepreneurial conviction, whereas extrinsic motivation had no significantly direct effects on both entrepreneurial conviction and preparation. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was partially supported. The effect of positive emotion on entrepreneurial conviction was nonsignificant, whereas the effect of positive emotion on entrepreneurial preparation was significantly negative. Negative emotion positively predicted both entrepreneurial conviction and preparation. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was partially supported. In addition, the direct effects of cognitive load on both entrepreneurial conviction and preparation were nonsignificant, whereas the direct effects of metacognition on both entrepreneurial conviction and preparation were significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was partially supported. Finally, self-efficacy positively predicted both entrepreneurial conviction and preparation. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Discussion

Direct effects

Through the CFA, this study concludes that the entrepreneurial intentions of Taiwanese CEE students comprise two factors (conviction and preparation), thus supporting the findings of previous studies (Liñán & Chen, 2009; Wang et al., 2014). In this study, conviction refers to a strong belief or opinion towards entrepreneurial career commitment, and preparation refers to the activities or processes that prepare a person for entrepreneurship.

The current study contributes to an understanding regarding the levels of influences of psychological factors on the entrepreneurial intentions of CEE students. According to the results regarding direct effects, self-efficacy influenced entrepreneurial conviction the most, followed by negative emotion, intrinsic motivation, and metacognition. By contrast, negative emotion influenced entrepreneurial preparation the most, followed by self-efficacy and positive emotion (a negative effect). Previous studies have indicated that metacognition is necessary for entrepreneurial performance (Frese, 2006; Haynie et al., 2010), though its effect was significant only on entrepreneurial conviction in this study. The function of metacognition is bridging the gap between intention and action (Van Gelderen, 2009), but its effect was nonsignificant on entrepreneurial preparation; this is a crucial topic that requires further research.

Regarding practical implications, the results indicate that CEE educators should encourage students and assist them in building their efficacy to engage in entrepreneurial activities. Educators should consider linking their students’ negative emotions and intrinsic motivations to stimulate their entrepreneurial intentions and foster their entrepreneurial behaviour. Goethner et al. (2012) indicated that entrepreneurial intentions enabled predicting. Possible strategies for CEE educators to enhance student self-efficacy beneficial for fostering entrepreneurial behaviour include constructing challenging and proximal goals, setting appropriate task demands and expectations, demonstrating confidence in students, and promptly recognising and praising effort. Strategies related to negative and positive emotions can include promoting undesirable attitudes towards the current status of the job market, unsatisfied quality of life in the workplace, relieving mental strain towards career choice, and decreasing the fear of failure in entrepreneurship. Strategies for enhancing intrinsic motivation can include arousing student curiosity and interest, encouraging students to work purposefully, offering various self-monitoring tasks, and encouraging feedback.

Interactive effects

The results of the interactive effect resulting from intrinsic motivation and cognitive load on entrepreneurial intention reveal that the levels of intention of high-IM (high intrinsic motivation) students increase in response to increased levels of cognitive load. However, the levels of intention of low-IM students decrease in response to increased levels of cognitive load. Therefore, the entrepreneurial intention of students is greatly influenced by intrinsic motivation, considering the impact of cognitive load. In addition, the results of the interactive effect caused by intrinsic motivation and metacognition on entrepreneurial conviction indicate that the entrepreneurial conviction of students exhibiting low levels of intrinsic motivation was particularly beneficial when their metacognitive capacity increased.

The results of the interactive effect caused by negative emotion and positive emotion on entrepreneurial intention reveal that the levels of intention of high-NE (high negative emotion) students decrease in response to increased levels of positive emotion. However, the levels of intention of low-NE students increase in response to increased levels of positive emotion. Therefore, positive emotion may serve as a trigger to facilitate the entrepreneurial intention of low-NE students, but not of high-NE students. Furthermore, the results of the interactive effect caused by negative emotion and self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intention reveal that the levels of intention of both high-NE and low-NE students increase in response to increased levels of self-efficacy. The increase of high-NE students’ intention is stronger than that of low-NE students.

Regarding practical implications, our findings suggest that cognitive load is not a critical factor affecting entrepreneurial intention, if intrinsic motivation remains at a high level. Thus, CEE educators should focus on encouraging low intrinsic-motivation students to increase their metacognitive capacity. According to the link between entrepreneurial intention and behaviour, proposed by Goethner et al. (2012), possible strategies for enhancing metacognition include activating background knowledge, assisting students in goal setting, facilitating practice in planning and monitoring, and supporting student self-regulatory processes. Our findings also indicate that negative emotion reliably predict entrepreneurial intention, but suggest that students exhibiting various levels of negative emotion require different strategies to facilitate their entrepreneurial intention. CEE educators should pay attention not only to negative emotion (such as unsolicited attitudes towards their current employment status) and self-efficacy but also to the combined strategy of these two psychological factors to stimulate their entrepreneurial conviction and pursue their goals.

Conclusion, research limitations, and future research

This study could serve as a reference for initiating a wide exploration of relevant topics from the perspective of entrepreneurship. The results of this study provide several valuable conclusions. First, self-efficacy exerted the strongest direct effects on entrepreneurial conviction, followed by negative emotion, intrinsic motivation, and metacognition. Negative emotion exerted the strongest direct effects on entrepreneurial preparation, followed by self-efficacy and positive emotion. In addition, an increase in cognitive load increases the entrepreneurial intention of students exhibiting high intrinsic motivation and reduces the intention of students exhibiting low intrinsic motivation. An increase in metacognition increases the entrepreneurial conviction of students exhibiting either high or low intrinsic motivation. Moreover, an increase in positive emotion decreases the entrepreneurial intention of students exhibiting high negative emotion and increases the intention of students exhibiting low negative emotion. An increase in self-efficacy increases the entrepreneurial intention of students exhibiting either high or low negative emotion.

Although this study expands the findings of previous research, it is not without limitations. First, we used self-reported scales for empirical validity and to simplify the process of administering the surveys; this may have caused common method bias. The survey employed in this study contained no sensitive questions, and the consistency of research results between the CFA in this study and that of previous studies supports the factor structure of the measures. Based on both studies of Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff (2003) and Malhotra, Kim, and Patil (2006), we adopted simple measures, carefully selected instruments, and offered necessary feedback after a survey to decrease this bias and to minimize this limitation. Second, we used the data of 815 CEE students from three universities in Taiwan. Further studies should use a larger sample or conduct international comparisons to discuss the possible differences resulting from regional distribution, as indicated by Obschonka et al. (2013).

Third, we did not adopt the leading established intention models in entrepreneurship research, such as Shapiro’s entrepreneurial event model or the models of Ajzen and Fishbein, because we did not want to mimic current research; rather, we sought to explore alternative approaches. In addition, because the research subjects of the present study were university students, the selection of psychological factors in this study was based on the perspective of educational psychology rather than on entrepreneurship models or research. Fourth, previous studies have indicated that gender and cultural concerns influence entrepreneurial intention (Goethner et al., 2012; Obschonka et al., 2013). Although these concerns were not the focus of the present study, they warrant further investigation, particularly to test whether gender plays a moderating role, and to analyse the impact of diverse sociocultural and economic factors.

The results of this study provide a basis for further testing the relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurial practices. Fayolle et al. (2006) asserted that entrepreneurial intention could function as a catalyst for action; hence, we considered the following questions. First, how can entrepreneurial intentions stimulate realistic practices? Second, what if we treat negative emotion or self-efficacy as a mediator in the structural model? Third, do domains differ amongst CEE programmes regarding the relationship between the psychological factors and entrepreneurial intentions examined in this study? If so, what are the implications of these differences? We anticipate that the answers to these questions will yield insights into educational strategies for CEE education.

closing remarks

This study is unlike typical studies on entrepreneurship and the CEE engineering profession in particular. The results provide several contributions to CEE and entrepreneurship education. First, few studies have thoroughly examined the relationships between psychological factors and entrepreneurial intention in CEE students. This study developed a novel approach, provided evidence regarding this relationship, and discussed the practical implications of the findings. Second, most relevant studies have examined the direct effects of selected psychological factors on entrepreneurial intention, whereas the current study additionally tested the interactive effects amongst psychological factors on entrepreneurial intention. Third, entrepreneurship is crucial because it facilitates economic efficiency, innovative product and service development, and new employment opportunities. Enhancing student interest and career choice in professional practice is amongst the primary goals of engineering educators. However, engineering colleges have not acknowledged the importance of entrepreneurship. This study clarifies the facilitative role that psychological factors can play in enhancing entrepreneurial intention.

The findings of this study are sufficiently promising to warrant further inquiry into this topic. Technopreneurship cannot be achieved without feasible entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurial intentions cannot be facilitated without a careful consideration of the interplay of diverse psychological factors. The findings of this study are intended as a reference for initiating a wider exploration of this topic.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50(6), 179-211.

- Bagozzi, R. P., and Phillips, L. W. (1982). Representing and testing organizational theories: A holistic construal. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27(3), 459-489.

- Bandura, A. (2000). Cultivate self-efficacy for personal and organizational effectiveness. In E. A. Locke (Ed.), Handbook of principles of organization behaviour (pp. 120-136). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intentinon. The Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442-453.

- Cardon, M. S., Foo, M.-D., Shepherd, D., and Wiklund, J. (2012). Exploring the heart: Entrepreneurial emotion is a hot topic. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(1), 1-10.

- Carsrud, A., and Brännback, M. (2012). Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9-26.

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., and Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62-83.

- Chen, L. (2013). IT entrepreneurial intention amongst college students: An empirical study. Journal of Information Systems Education, 24(3), 233-243.

- Chen, S.-C., and Chen, H.-H. (2015). How does creativity mediate the influence of personality traits on entrepreneurial intention? A study of multimedia engineering students. Journal of Information Communication, 5(2), 73-86.

- Choi, J. N., Price, R. H., and Vinokur, A. D. (2003). Self-efficacy changes in groups: Effects of diversity, leadershipand group climate. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 24(4), 357-372.

- Cooper, A. C., and Dunkelberg, W. C. (1986). Entrepreneurship and paths to business ownership. Strategic Management Journal, 7(1), 53-68.

- Covin, J. G., and Slevin, D. P. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75-87.

- Dej, D. (2008). The nature of entrepreneurial motivation. In J. A. M. Leon, M. Gorgievski, and M. Lukes, Teaching psychology of entrepreneurship: Perspective from six European countries (pp. 81-102). Madrid, Spain: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia Madrid.

- Fayolle, A., Gailly, B., and Lassas-Clerc, N. (2006). Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education programmes: A new methodology. Journal of European Industrial Training, 30(9), 701-720.

- Frese, M. (2006). The psychological actions and entrepreneurial success: An action theory approach. In J. R. Baum, M. Frese, and R. A. Baron (Eds.). The Psychology of Entrepreneurship. Lawrence Erlbaum: SIOP Frontier Series.

- George, J. M. (2000). Emotions and leadership: The role of emotional intelligence. Human Relations, 53(8), 1027-1055.

- Goethner, M., Obschonka, M., Silbereisen, R. K., and Cantner, U. (2012). Scientists’ transition to academic entrepreneurship: Economic and psychological determinants. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(3), 628-641.

- Gerba, D. T. (2012). Impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of business and engineering students in Ethiopia. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 3(2), 258-277.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/ Prentice Hall.

- Harter, S. (1981). A new self-report scale of intrinsic versus extrinsic orientation in the classroom: Motivational and informational components. Developmental Psychology, 17(3), 300-312.

- Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D. A., Mosakowski, E., and Eagly, P. C. (2010). A situated metacognitive model of the entrepreneurial mindset. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 217-229.

- Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D. A., and Patzelt, H. (2012). Cognitive adaptability and an entrepreneurial task: The role of metacognitive ability and feedback. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 237-265.

- Hsu, Y., Liang, C., and Chang, C.-C. (2014). The mediating effects of generative cognition on imagination stimulation. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 51(5), 544-555.

- Hu, L.-T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1-55.

- Kaltenecker, N., and Hörndlein, C. (2013). The drivers of entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical study amongst information systems and computer science students. Proceedings of the Nineteenth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Chicago, Illinois, August 15-17, 2013.

- Kamau-Maina, R. (2008). Encouraging entrepreneurial intentions: The role of university/college environments and experiences. Weatherhead School of Management, Case Western Reserve University, Retrieved 26 December, 2014, http://digitalcase.case.edu:9000/fedora/get/ ksl:weaedm131/weaedm131.pdf

- Klincewicz, K. (2012). Political perspective on technology alliances: the case of Microsoft and Google. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 8(1), 5-34.

- Lans, T., Gulikers, J., and Batterink, M. (2010). Moving beyond traditional measures of entrepreneurial intentions in a study amongst life-sciences’ students in the Netherlands. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 15(3), 259-274.

- Leon, J. A. M., Gorgievski, M., and Lukes, M. (2008). Teaching psychology of entrepreneurship: Perspective from six European countries. Madrid, Spain: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia Madrid.

- Liang, C., Hsu, Y., and Chang, C.-C. (2013). Intrinsic motivation as a mediator on imaginative capability development. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 8(1), 109-119.

- Liang, C.-T., Chia, T.-L., and Liang, C. (2015). Effect of personality differences in shaping entrepreneurial intention. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 6(4.1), 166-176.

- Lightsey, O. R., Maxwell, D. A., Nash, T. M., Rarey, E. B., and McKinney, V. A. (2011). Self-control and self-efficacy for affect regulation as moderators of the negative affect-life satisfaction relationship. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25(2), 142-154.

- Liñán, F., and Chen, Y. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593-617.

- Malhotra, N. K., Kim, S. S., and Patil, A. (2006). Common method variance in IS research: A comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research. Management Science, 52(12), 1865-1883.

- Markman, G. D., Balkin, D. B., and Baron, R. A. (2002). Inventors and new venture formation: The effects of general self-efficacy and regretful thinking. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(2), 149-165.

- Ministry of Education (2015). Important Statistics. Retrieved 30 December, 2014, http://www.edu.tw/pages/detail.aspx?Node=4076&Page=20047 &Index=5&WID=31d75a44-efff-4c44-a075-15a9eb7aecdf.

- Murah, M. Z., and Abdullah, Z. (2012). Entrepreneurial intentions amongst computer science students at Faculty of Information Science and Technology: An empirical study. Procedia - Social and Behavioural Sciences, UKM Teaching and Learning Congress.

- Neck, C. P., Neck, H. M., Manz, C. C., and Godwin, J. (1999). “I think I can; I think I can”: A self-leadership perspective toward enhancing entrepreneur through patterns, self-efficacy, and performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 14(6), 477-501.

- Obschonka, M., Schmitt-Rodermund, E., Silbereisen, R. K., Gosling, S. D., and Potter, J. (2013). The regional distribution and correlates of an entrepreneurship-prone personality profile in the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom: A socioecological perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(1), 104-122.

- Ooi, Y. K., and Ahmad, S. (2012). A study amongst university students in business startups in Malaysia: Motivations and obstacles to become entrepreneurs. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(19), 181-192.

- Paas, F. G. W. C., and van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (1994). Instructional control of cognitive load in the training of complex cognitive tasks. Educational Psychology Review, 6(4), 351-371.

- Patzelt, H., and Shepherd, D. A. (2011). Negative emotions of an entrepreneurial career: Self-employment and regulatory coping behaviours. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(2), 226-238.

- Pittaway, L., and Cope, J. (2007). Entrepreneurship education: A systematic review of the evidence. International Small Business Journal, 25(5), 479-510.

- Podoynitsyna, K., Van der Bij, H., and Song, M. (2012). The role of mixed emotions in the risk perception of novice and serial entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(1), 115-140.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioural research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879-903.

- Prodan, I. and Drnovsek, M. (2010). Conceptualizing academic-entrepreneuria intentions: An empirical test. Technovation, 30(5-6), 332-347.

- Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

- Sánchez, J. C. (2012). Entrepreneurial intentions: The role of the cognitive variables. In T. Burger-Helmchen (Ed.). Entrepreneurship: Born, made and educated (pp. 27-50). New York: InTech.

- Schraw, G. and Dennison, R.S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19, 460-475.

- Shane, S. (2004). Encouraging university entrepreneurship? The effect of the Bayh-Dole Act on university patenting in the United States. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(1), 127-151.

- Szirmai, A., Naude, W., and Goedhuys, M. (2011)(Eds.). Entrepreneurship, innovation, and economic development. Oxford University Press.

- Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Thompson, E. R. (2009). Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 669-694.

- Tuccitto, D. E., Giacobbi, Jr., P. R., and Leite, W. (2010). The internal structure of positive and negative affect: A confirmatory factor analysis of the PAMAS. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70, 125-141.

- Urban, B. (2012). Applying a metacognitive perspective to entrepreneurship: Empirical evidence on the influence of metacognitive dimension on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 20(2), 203-225.

- Van Gelderen, M. (2009). From entrepreneurial intention to action initiation. Retrieved 21 December, 2014, http://sbaer.uca.edu/research/icsb/2009/ paper2.pdf

- Vesalainen, J., and Pihkala, T. (1999). Motivation structure and entrepreneurial intentions. Retrieved 30 December, 2014, http://fusionmx.babson.edu/ entrep/fer/papers99/II/II_B/IIB.html

- Wang, J.-H., Peng, L.-P., and Liang, C. (2014). Developing and testing the psychological influence, rural practice, and entrepreneurial intention scales. Review of Agricultural Extension Science, 31, 72-95.

- Waugh, C. E. (2013). The regulatory power of positive emotions in stress: A temporal functional approach. In Kent, M., M. C. Davis, and J. W. Reich (Eds.) The resilience handbook: Approaches to stress and trauma (pp. 74- 75). London, UK: Routledge.

- Welpe, I. M., Spörrle, M., Grichnik, D., Michl, T., and Audretsch, D. B. (2012). Emotions and opportunities: The interplay of opportunity evaluation, fear, joy, and anger as antecedent of entrepreneurial exploitation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(1), 69-96.

- Zain, Z. M., Akram, A. M., and Ghani, E. K. (2010). Entrepreneurship intention among Malaysian business students. Canadian Social Science, 6(3), 34-44.

- Zakarevičius, P., and Župerka, A. (2010). Expreeion of emotional intelligence development of students’ entrepreneurship. Economics and Management, 15, 865-873.

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S. and Hills, G. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265-1272.

Biographical notes

Chao-tung Liang is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Cultural Creativity and Digital Media Design, Lunghwa University of Science and Technology, Taoyuan, Taiwan. He gained his Master degree in the Radio and Television program at the National Taiwan University of Arts, Taiwan. His current research interests focus on: communication education, multimedia design, media psychology, and entrepreneurship. Assistant Professor Liang can be reached via This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Dr. Jia-Ling Lee is an Associate Professor in the Department of Radio, Television and Film, Shih Hsin University, Taipei, Taiwan. She gained her PhD in the Educational Technology program at the University of Florida, USA. Her current research interests focus on: media convergence, new media, multimedia design, and e-learning. Associate Professor Lee can be reached via This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Dr. chaoyun Liang is a Professor in the Department of Bio-Industry Communication and Development, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan. He gained his PhD in the Instructional Systems Technology program at the Indiana University, USA. His current research interests focus on: imagination & creativity, entrepreneurship & social enterprise, and agrirural communication & marketing. Professor Liang can be reached via cliang@ntu. edu.tw.