Agata Sudolska, Dr hab., prof. UMK, The Faculty of Economic Sciences and Management, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń, Poland. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Andrzej Lis, Dr, The Faculty of Economic Sciences and Management, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń, Poland. Doctrine and Training Centre of the Polish Armed Forces, Bydgoszcz, Poland. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Abstract

The aim of the paper is to develop a model of successful collaborative learning for company innovativeness. First of all, the paper explores the issue of inter-firm learning, focusing its attention on collaborative learning. Secondly, inter-firm learning relationships are considered. Thirdly, the ex ante conditions of collaborative learning and the intra-organizational enhancers of inter-firm learning processes are studied. Finally, a model of the critical success factors for collaborative learning is developed.

Keywords: innovativeness, inter-firm learning, inter-firm relationships, collaborative learning, critical success factors for collaborative learning.

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, the ability to learn is perceived as one of the most important intangible assets that a firm can possess. This corresponds with the view that knowledge is a very suitable resource to be used for building the enterprise’s competitive advantage (Amit and Schoemaker, 1993; Prahalad and Hamel, 1990). As highlighted by Teece (1998, p. 62) “the competitive advantage of companies in today’s economy stems not from market position, but from difficulty to replicate knowledge assets and the manner in which they are deployed”. This opinion refers to the fact that knowledge meets the most important characteristics of strategic resources necessary to build long term competitive advantage. Knowledge, as a typical strategic resource, is: valuable, rare, difficult to imitate and difficult to replace by other resources (cf. Barney, 1991).

In contemporary business, the idea of inter-firm cooperation is said to be one of the key elements of the modern management model that answers the challenges of the global economy. Nowadays, the issue that becomes significant is company innovativeness which has been recognized as the foundation for strengthening its competitiveness. Due to spreading “New Economy” conditions, the process of creating innovations is changing. Market observation proves that very often innovations are stimulated by inter-firm learning which takes place within the relationships with other companies (Mitra, 2000, p. 228-229; Vanhaverbeke, 2008, p. 208., Wang, Rodan, Fruin and Xu, 2014, p. 484).

There is a considerable agreement among researchers on the fact that innovation can be stimulated through interactive learning processes. Every enterprise operates in a network of relationship ties with its customers, suppliers, competitors, business support organizations etc. This network of business relationships influences the single company’s capacity to be innovative (Mohannak 2007; Chesbrough, 2008). Still growing number of authors (e.g. Mu, Peng and Love, 2008; Cowan, 2007; Vanhaverbeke, 2008; Kastalli and Neely, 2013) claim that enterprises which establish and develop inter-firm relationships are more successful in the field of innovation than the firms that do not implement cooperation strategy. It is becoming clear that complex challenges of today’s environment require collaborative and innovative solutions. Companies acting alone are not best placed to seize available opportunities or respond to the challenges they face (Kastalli and Neely, 2013, p. 4). This is related to the fact that inter-firm cooperation improves the single enterprise innovative capacity by reducing uncertainty through information and knowledge access, sharing, screening and by establishing a longer term focus on relationship building in order to develop organizational competences. Inter-firm business relationships create the opportunities to reach global markets, absorb new technologies, share knowledge, human and material resources (Saarenketo, Kuivalainen, Kylaheiko and Puumalainen, 2004).

The enhancement of firm’s ability to learn very often becomes the main reason for entering into relationships with other enterprises. It refers to the fact that firm’s innovativeness and competitiveness depend on its ability to integrate different kinds of knowledge and to coordinate the knowledge flow among different organizations in the market. Taking this into account, today many enterprises adopt cooperative strategies with the intention of acquiring new knowledge and know-how. They realize that focusing on creating interfirm sustainable relationships results in establishing contact with “knowledge milieus” beyond their local environments. This means that they can gain the access to technological competencies and know-how that are not available in their local environments. While having established external relationships, companies are more able to gain assistance with technology development and innovation when a particular need arises (Mohannak, 2007, p. 246). What is more, as proved by Yang, Lin and Peng (2011), the inter-firm learning between the members of a strategic alliance is a factor triggering acquisitions of alliance partners. Making a distinction between exploration and exploitation alliance learning (cf. March 1991), Yang et al. (2011) find that it is particularly applicable in the case of exploration learning which is a long-term approach oriented to the development of new competencies in order to adapt to the changing environment.

The opinions and findings presented above highlight the role of interfirm learning processes in strengthening company innovativeness. Interfirm learning, considered as an element of the cooperative strategy, seems to be a prerequisite for business success. Collaborative learning is one of factors motivating managers to establish inter-firm cooperation. In order to benefit from collaborative learning outcomes, cooperating companies should manage these processes and create conditions which enable such initiatives to flourish. The antecedents and determinants of effective inter-firm learning and knowledge transfer are often discussed in the literature (cf. Cummings and Teng, 2003; Martinkenaite 2011; Lawson and Potter, 2012) which confirms the importance of the problem. Nevertheless, the understanding of critical success factors for effective inter-firm learning still seems to remain unclear and to need further exploration.

Therefore, the aim of the paper is to develop a model of successful collaborative learning for company innovativeness. In order to achieve the main aim of the paper, the following operational objectives have been established: (1) to discuss the problems of the structural conflict between competition and collaboration which are typical of inter-firm learning and to identify the types of collaborative learning; (2) to define and understand interfirm learning relationships; (3) to identify and study the ex ante conditions of successful collaborative learning; and (4) to identify and study the intraorganizational enhancers of successful collaborative learning.

The study is based on purposeful selection of articles (narrative review). The sources used for analysis encompass two main areas (types) of literature: knowledge management and strategic management. The paper provides an overview of recent contributions to the literature on inter-organizational learning and inter-firm relationships.

The paper is structured around the aforementioned research objectives. First of all, the paper explores the issues of inter-firm learning, focusing its attention on collaborative learning. Secondly, the issues of inter-firm learning relationships are considered. Thirdly, the ex ante conditions of collaborative learning and the intra-organizational enhancers of inter-firm learning processes are studied. Finally, a model of the critical success factors for collaborative learning is developed.

INTER-FIRM LEARNING: BETWEEN COMPETITION AND COLLABORATION

Organizational learning is the essence of knowledge management. As highlighted by Jashapara (2004, p. 12), knowledge management can be defined as „the effective learning processes associated with exploration, exploitation and sharing of human knowledge (tacit and explicit) that use appropriate technology and cultural environments to enhance an organization’s intellectual capital and performance”. In fact, organizational learning combines the potential of knowledge with the efforts for the improvement and development of an organization. Such views are embodied in the definition by Fiol and Lyles who claim that “[o]rganizational learning means the process of improving actions through better knowledge and understanding” (Fiol and Lyles, 1985, p. 803).

Inter-firm learning is perceived as an extension of organizational learning, developing enterprise knowledge and providing new insights into the firm’s strategy. It is a process of acquiring, disseminating, interpreting, using and storing the information within or across the firm that leads to creating knowledge affecting its innovativeness and competitiveness on the market. Inter-firm learning takes place within inter-firm structures such as different types of business relationships and networks that enable companies to tap into technologies, products and markets which would otherwise be beyond their own resources (Mathews, 1996; Makinen, 2002). While establishing any business relationship, a firm becomes a part of the cooperative interaction process that results in learning more about itself as well as leveraging its competences through absorption of new knowledge.

Generally, there are two possible learning relationships between cooperating partners: collaborative learning and competitive learning. The structural conflict between cooperation and competition is an inherent feature of any inter-firm relationship, in particular a strategic alliance. The same dilemma is highly visible in the area of inter-firm learning. Collaborative learning is understood as a reflective cognitive process in which the engaged parties (enterprises) capitalize on one another’s resources and skills. They engage in a common task where each company depends on and is accountable to each other. This refers to the situation in which learning takes place through explicit or implicit collaborative efforts. Collaborative learning is characterized by mutual benefits for both partners willing to develop and strengthen cooperation over time in order to create the effect of synergy. Competitive learning occurs when one of partners tries learn as much as possible from the other one without contributing to mutual learning (Child, Faulkner and Tallman, 2005, p. 279-282). The nature of the conflict from the perspective of inter-firm learning is very accurately noticed by Mohr and Sengupta (2002, p. 282) who claim that “[o]n one hand, inter-firm learning is a desirable extension of organizational learning, developing a firm’s knowledge base, and providing fresh insights into strategies, markets, and relationships. On the other hand, inter-firm learning can lead to unintended and undesirable skills transfer, resulting in the potential dilution of competitive advantage”. In consequence, as observed by Mohr and Sengupta (2002, p. 286-287), two opposite pictures of inter-firm learning (“rosy” vs. “risky”) are painted in the literature. According to the proponents of the “rosy” picture, an interfirm learning partnership enables cooperating companies to achieve better competitive position and to improve their organizational skills. An effective knowledge transfer is stimulated by interdependence of partners, openness, trust and the variety of interaction channels. Partners trust each other, show a high level of commitment to the relationship and willingly share knowledge. The relationships between cooperating organizations are characterized by high, symmetrical interdependence and close interpersonal ties. Integrative conflict resolution, harmony and the longevity of a relationship are the indicators of the partnership success. The opposite, “risky” picture of interfirm learning focuses its attention on potential threats of losing valuable information and knowledge which may result in the increased vulnerability to competition. Knowledge transfer is primarily associated with outlearning one’s partner by another. Therefore, it is recommended to restrict learning interactions in order to reduce potential knowledge leakages. Relationships between partners are characterized by: a lower level of trust and commitment, limited information and knowledge sharing, asymmetrical interdependence and more distant interpersonal relationships. The measures of partnership success include: some contentiousness and ending partnership relationships when learning objectives are attained.

Nowadays, collaborative learning that is a part of inter-firm relationships provides the building blocks to access new or lacking capabilities. By enlarging one firm’s knowledge base and accessing the knowledge that can augment its sources of expertise, collaborative learning may help a company to strengthen its innovativeness and its market position. Due to this, collaborative learning has far-reaching implications for filling knowledge assets gaps existing in firms and improving their ability to create and commercialize innovations (Gulati, 2007, p. 31-72; Donaldson and O’Toole 2007, p. 27-28).

The following forms of collaborative learning are identified: learning from experience, learning about a partner, learning from a partner and learning with a partner (Inpken, 2002; cited after Child et al., 2005, p. 275-279). Firstly, enterprises have the opportunities to learn from their partners’ experience. Experiential learning can be useful for planning and managing subsequent partnership initiatives. Lessons learned from previous partnership play an important role when making decisions on joining another one. Secondly, at the pre-relationship stage, learning about a partner organization, its motivations and capabilities is necessary to make right decisions and properly prepare a partnership agreement. When a partnership is established two remaining forms of learning occur. Learning existing knowledge and skills from a business partner is the first option. This kind of learning comes about through the transfer of knowledge into a different company for which it represents a new input. Such a transfer is usually observed while a firm aims at technological complementarity and its development or launching new products. Learning with a business partner is the second one. This type of collaborative learning includes the creation of new knowledge or at least a substantial transformation of the knowledge already existing within a particular relationship. Such a kind of process refers to mutual learning which occurs through an integration of different inputs offered by cooperating enterprises. In recent decades it has been recognized that the motive behind most technology alliances is to capture the innovation synergies that may arise from pooling complementary knowledge and capabilities.

INTER-FIRM LEARNING RELATIONSHIPS

Recent years have seen an increased interest in the issues concerning the development of firm’s learning abilities and the process of creating innovations. As a consequence, today there is a considerable agreement among researchers and practitioners on the view that innovations are generated mainly through cooperation and learning with other companies, such as suppliers or even competitors with whom the firms set up strategic alliances. Such a tendency refers to the fact that various inter-firm relationships enable partners to develop new capabilities. This results in filling several assets gaps existing in cooperating companies and in improving their ability to learn and create new processes or products (King, Covin and Hegarty, 2003, p. 592; Perks, 2004; p. 39-41; Stańczyk-Hugiet, 2013, p. 66-67).

The idea of developing inter-firm relationships focused on increasing firms’ potential for creating innovations is an inherent part of the open innovation paradigm that treats R&D as an open system. This paradigm has been introduced by Chesbrough who suggests that valuable ideas can come from inside or outside the firm and can go to the market from inside or outside it as well. In other words, the open innovation paradigm proposes the use of purposive inflows and outflows of knowledge to accelerate internal innovation, and expand the markets for external use of innovation (Chesbrough, 2008, p. 1). While open innovation is practiced firm’s boundaries are “porous”. It means they allow knowledge to flow in and out of the company at any point during the R&D process. Company policy dictates what kind of knowledge can flow in which direction and under what circumstances (Gaule, 2006, p. 13). Due to aforementioned, we may say that open innovation is almost by definition related to establishing ties of innovating companies with other organizations on the market. It implies an extensive use of inter-firm ties to insource external ideas and to market internal ideas through external market channels outside a company’s current business (Vanhaverbeke, 2008, p. 205- 208).

When considering the issue of inter-firm learning relationships, first of all we should define and understand what inter-firm business relationships are. Some authors emphasize that it is necessary to distinguish between relationships and interactions. “The relationship elements of the behavior are rather general and long-term in nature. Interactions, by contrast, represent the here and now of inter-firm behavior and constitute the dynamic aspects of relationships” (Easton, 1992, p. 8). Therefore, we can point out that business relationships are the relatively enduring transactions, flows and linkages that occur among or between a company and one or more other organizations in the environment. What is typical, inter-firm relationships encompass a wide range of elements such as mutual orientation of cooperating parties, the interdependence between business partners as well as some investments each firm has made in particular relationships (Easton, 1992, p. 8). Such investments are understood as the undertakings which allocate specific resources to generate or acquire assets to be used by the partners in the future (Johansson and Mattson, 1985).

Given the fact that nowadays firm’s competitiveness is associated with its innovativeness and the ability to learn, the so called inter-firm learning relationships can be identified. Companies establishing such business relationships are aimed at knowledge transfer or common creation of new knowledge that is needed by them to sustain their competitiveness. Such relationships are based on learning from each other or together in order to create valuable knowledge assets through synergy that neither would have been able to achieve by the cooperating companies acting individually (Sudolska, 2011, p. 79). What is significant, enterprises that are embedded in such partnerships agree to change the way they do business, integrate and jointly control some parts of their business systems. They also agree to share knowledge in the benefit of cooperation.

Combining the findings by Child and Markóczy (1993) and Inpken (1995), Child et al. (2005, p. 289-292) identify the following forms of inter-firm learning relationships: forced learning, imitation or experiential learning, blocked learning, received learning, integrative learning, segmented learning and non-learning. In their typology they distinguish three features of cooperative learning situations: changes in cognitive and behavioral learning and the level of motivation to learn. Considered rather as an adaptation, forced learning is typical of asymmetric partnerships, when a less powerful partner changes its behaviors but no cognitive internalization is observed and motivation to learn is very low. As motivation increases to the moderate level, learning by imitation emerges. This type of learning is typical of early stages of collaboration and may evolve into more advanced forms. In case of forced learning and learning by imitation, the lack of knowledge internalization and understanding is a key problem. An opposite situation is noticed in case of blocked learning. This is the situation when the personnel who have received training from a partner company and have internalized new knowledge are not able to put this knowledge into practice due to insufficient position in the organizational hierarchy or the lack of financial resources (cognitive change and high motivation are not able to trigger changes in organizational behavior). In case of received learning and integrative learning, both partner organizations change their cognitions and behaviors. The difference is whether it is an asymmetric (unilateral) motivation to learn (received learning) or both partners willingly share their knowledge and skills (integrative learning). When partner motivation for cooperative learning is low and changes in cognition/behavior are narrowed, segmented learning is observed. Finally, non-learning is the last possible situation in cooperative partnerships studied from the inter-firm learning perspective.

While analyzing the matter of inter-firm learning relationships focused on collaborative learning, we should remember that among the benefits of such business relationships several authors point out learning specific skills as well as developing competencies. Learning through business relationships is an important intangible benefit of inter-firm cooperation due to the fact that it helps a firm to secure a global market share and its competitive advantage. Moreover, developing core competencies thanks to inter-firm relationships enables a company to leverage knowledge gained from relationship partners in other markets (Simonin, 1997; Berdrow and Lane, 2003; Palakshappa and Gordon 2007).

Concluding, inter-firm relationships focusing on learning on one hand refer to the company’s competence building and on the other hand to the competency leveraging that means applying competencies to contemporary market opportunities. Both mentioned actions are taken by companies to generate learning resources that enable them to increase their innovativeness (Mitra, 2000). Taking this into account we may say that a company knowledge base is influenced by and partly derived from the business relationships in which they are embedded.

THE EX ANTE CONDITIONS OF SUCCESSFUL COLLABORATIVE LEARNING

Successful collaborative learning to occur requires some ex ante conditions which are the prerequisites of effective inter-firm learning processes. Child et al. (2005, p. 282-289) enumerate the three following requirements for a company to be able to learn effectively from other members of a strategic alliance: partner intensions, their capacity to learn and ability to convert knowledge into an organizational property.

First of all, partner intentions refer to the company’s goals for particular relationship. According to Beamish and Berdrow (2003), for learning to provide real value there needs to be a conscious intent to learn. In regard to partner intentions, collaborative and competitive motivations should be distinguished. Organizations showing collaborative intentions are generally oriented to long-term relationships aimed at accessing partner knowledge and skills. Companies driven by competitive intentions focus on enhancing their competitive positions by internalizing partner knowledge and skills. Achieving their aim, such companies are not interested in the longevity of an alliance (Child et al., 2005, p. 283-284). With the regard to the intentions of the firms creating the relationship aimed at learning, it is necessary to emphasize the level of enterprise’s determination concerning the need for new knowledge. According to the survey conducted on 147 companies by Simonin (1997), learning intent is a very strong and consistent predictor of knowledge transfer within business relationships.

Secondly, partner capacity to learn is another prerequisite of effective inter-firm learning. Such an ability depends on knowledge transferability from one partner to another, receptivity of organization members to new knowledge, their ability to recognize the value of external knowledge, assimilate and apply it and on partner lessons learned from previous relationships (Simonin, 2004, p. 410).

Thirdly, the requirement of converting knowledge into an organizational property refers to the company ability to manage interactions between tacit and explicit knowledge. As such, it can be explained by the Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) model describing four different modes of organizational knowledge conversions: socialization, externalization, combination and internalization. Although some researchers (e.g. Gourlay, 2003; Gourlay, 2006; Powell, 2007) criticize the SECI framework and its assumptions it remains one of the most seminal models describing knowledge conversion processes.

The company capacity to learn and its ability to convert knowledge into an organizational property may be explained by the concept of absorptive capacity popularized by Cohen and Levinthal (1990). According to these authors, absorptive capacity is the ability of a company to recognize the value of new external knowledge, assimilate it, and apply to commercial ends (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990, p. 128). Absorptive capacity includes four components: identifying and recognizing external knowledge, processing and understanding it, combining it with existing knowledge and applying the new knowledge to commercial ends (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Zahra and George, 2002). Firms differ in their abilities to acquire and use external knowledge. Recent research shows that firms operating under similar external conditions display notable differences in the features of their organizational knowledge bases which in turn affect their absorptive capacity (Nag and Giola, 2012, p. 422).

The ability to identify and recognize the value of external knowledge is the first step to develop the company's absorptive capacity. Several authors argue that enterprises that present a high level of receptivity to new knowledge are those which are most successful in learning together through business relationships (Hamel, 1991; Child et al., 2005, p. 285-287). Firm’s receptivity to new knowledge is recognized as a kind of business attitude. Today, there is a considerable agreement among writers and practitioners on the view that company’s receptivity refers to the ability to recognize the desired knowledge or/and to assess the potential of common creation of new knowledge with a particular partner. Such ability is directly related to company’s competences which result from the firm’s level of prior related knowledge (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Child et al., 2005, p. 285-286; Trott, 2008, p. 330). The next step in learning through knowledge absorption is combining the new knowledge with the one existing within the firm and applying the new knowledge to innovation. The success of these two steps depends on prior, related knowledge as well as the level of its resources that are engaged in the activities focused on gathering knowledge and embedding it within its own business routines (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Child et al., 2005, p. 286; Nag and Giola, 2012, p. 422). The all mentioned components of absorptive capacity are necessary and together they influence the extent to which knowledge received by a partner benefits its performance (Chang, Gong and Peng, 2012, p. 931).

The concept of absorptive capacity developed by Cohen and Levinthal (1990) has been reexamined and reconceptualized in subsequent studies. For instance, Zahra and Goerge (2002) highlight the dynamic character of absorptive capacity defining it as “a set of organizational routines and processes by which firms acquire, assimilate, transform and exploit knowledge to produce a dynamic organizational capability” (Zahra and Goerge, 2002, p. 186). The authors distinguish four dimensions of absorptive capacity and group them into two constructs: potential absorptive capacity (acquisition, assimilation) and realized absorptive capacity (transformation and exploitation). Moreover, they claim that previous studies have neglected the issue of contingent factors which determine the use of absorptive capacity to build up and strengthen the company competitive advantage. Therefore, Zahra and George (2002, p. 191-197) extend the catalogue of absorptive capacity antecedents listing among them: external sources and knowledge complementarity, experience, activation triggers (internal or external events stimulating a company to respond), social integration mechanisms and regimes of appropriability (“institutional and industrial dynamics that affect the firm’s ability to protect the advantages of (and benefits from) new products and processes”). Finally, Zahra and George (2002, p. 195-196) analyze the impact of absorptive capacity on the company competitive advantage. They argue that knowledge transformation and exploitation (realized absorptive capacity) are the key success factors for achieving competitive advantage and product development because they facilitate the use of knowledge for commercial purposes whereas knowledge acquisition and assimilation (potential absorptive capability), which enable an organization to explore new knowledge, are particularly important for sustaining competitive advantage.

The assumptions of Cohen and Levinthal’s (1990) concept of absorptive capacity and its reconceptualization by Zahra and George (2002) are reexamined by Todorova and Durisin (2007). In their study, they criticize some of Zahra and George’s (2002) proposals (e.g. the distinction between potential and realized absorptive capacity) and point out some ambiguities and omissions. Todorova and Durisin (2007, p. 782) propose to include power relationships (“that involve the use of power and other resources by an actor to obtain his or her preferred outcomes”) into the list of contingency factors and antecedents of absorptive capacity. Their proposal encompasses both intra-organizational power relationships and external relationships (e.g. with customers). As regards other antecedents, Todorova and Durisin (2007, p. 781) “argue that social integration mechanisms influence all components of absorptive capacity and that the influence can be either negative or positive according to the type of new knowledge and the type of knowledge processes. Then, they postulate further studies to investigate ambiguous effects of the regimes of appropriability both on absorptive capacity antecedents and outcomes (Todorova and Durisin (2007, p. 781-782). Moreover, referring to the assumption of dynamic nature of absorptive capacity, Todorova and Durisin (2007, p. 782-783) highlight the role of feedback links between the company absorptive capacity and its knowledge base.

Sun and Anderson (2010) reexamine the issue of absorptive capacity in the context of its relationship with the concept of organizational learning. They prove that absorptive capacity and organizational learning share conceptual affinity due to similarities in theoretical background, antecedents and observable outcomes. The key point of their reasoning is that “ACAP [absorptive capacity] should be considered as a specific type of OL [organizational learning] which concerns an organization’s relationship with external knowledge” (Sun and Anderson, 2010, p. 141). Among the antecedents of absorptive capacity and organizational learning, which are especially important from the point of view of this paper, Sun and Anderson (2010, p. 139-140) enumerate: external environment knowledge sources, “cross-functional interfacing, participatory decision-making, job rotation, social relationship, strategic focus, organizational structure, R&D effort, organizational crises and mental models”. A model describing a nature of relationship between absorptive capacity and organizational learning is the result of studies by Sun and Anderson (2010, p. 142). Their model illustrates relationships between the components of absorptive capacity identified by Zahra and George (2002) (i.e. knowledge acquisition, assimilation, transformation and exploitation) and the organizational learning processes enumerated by Crossan, Lane and White (1999) (i.e. intuition, interpretation, integration, institutionalization). Knowledge acquisition is considered as a learning capability including intuition and interpretation processes at individual and group levels of learning. Knowledge assimilation is a group learning activity involving interpretation processes. Knowledge transformation, observed at group and organizational levels, is related to integration processes. Knowledge exploitation involves the process of institutionalization at the organizational level. Another contribution of the discussed paper is the identification of factors influencing the aforementioned components of absorptive capacity. Sun and Anderson (2010) enumerate the following antecedents of:

- knowledge acquisition: type of intuition of the members of an organization who receive external knowledge (distinction between entrepreneurial and expert intuition);

- knowledge assimilation: dialogue, diversity of team members’ experience and an environment supporting innovativeness;

- knowledge transformation: ambidextrous leadership combining transactional and transformational styles and sand-pit experimentation enabling an organization to test new knowledge;

- knowledge exploitation: leaders’ ability to apply appropriate reward and recognition mechanisms and effective allocation of organizational resources.

In their conceptual framework, Mohr and Sengupta (2002, p. 289-297) claim that an effective knowledge transfer between cooperating partners is determined by the fit between ex ante relationship conditions and an appropriate type of corporate governance mechanism. According to their understanding an effective knowledge transfer should meet two requirements: to maximize desired learning and to minimize undesired learning (an access to sensitive information and knowledge). The ex ante relationship conditions include three main elements: type of knowledge, partner learning intent and the duration of the partnership. As regards the type of knowledge, the more knowledge is converted from tacit to explicit, the higher potential learning risks are observed. In case of partner learning intent, such a risk is aggravated as the intent shifts from knowledge access to knowledge internalization. The duration of a relationship depends on benefits for partner organizations: the higher benefits, the longer duration. In consequence, extending the time of a relationship results in more knowledge transfer between partners.

Concluding, the literature review enables us to identify the four following ex ante conditions of successful collaborative learning: (1) type of knowledge, (2) partners’ intensions, (3) partners’ receptivity and competences and (4) anticipated relationship duration.

COLLABORATIVE LEARNING ENHANCERS

In addition to the ex ante conditions discussed above, successful collaborative learning requires some elements of positive inter-firm potential such as: (1) corporate governance mechanisms within a business relationship, (2) trust between cooperating companies, (3) effective inter-firm communication, and (4) partner commitment. We define the aforementioned elements as collaborative learning enhancers. The notion of positive inter-firm potential is the extension of the concept of positive organizational potential coined and developed by Stankiewicz and his associates (2010, 2013). The roots of positive organizational potential derive from the Positive Organizational Scholarship movement (cf. Cameron, Dutton and Quinn, 2003) and the idea of company competitive potential (cf. Stankiewicz 1999, 2002) embedded in the Resource-Based View of an organization (cf. Barney, 1991).

Relationship governance mechanisms

Corporate governance mechanisms within a business relationship are directly related to the issue of control. Control as the aspect of relationship management, might be understood as a process whereby managers from partnering firms are able to initiate and regulate the conduct of activities in such a way that their results accord with the goals and expectations held by them (Child et al., 2005, p. 214). Control over a relationship is widely regarded as a critical factor for successful performance of any cooperation (Malhotra and Lumineau, 2011). For instance, the role of governance mechanisms for inter-firm learning is confirmed by the findings from the questionnaire survey among Taiwanese high-tech companies. As observed by Wu, Wu and Lo (2004, p. 461) “contractual governance and procedural governance are the two contributory factors of learning effectiveness and relationship performance in strategic alliance”. On the other hand, insufficient control can restrict partner’s ability to protect as well as efficiently utilize the resources it provides to the relationship and to achieve the goals it has set for a particular partnership (Child et al., 2005, p. 215).

The mechanisms of control introduced by the partners guarantee predictability of the course of events and improve the conduct of operational management within a relationship. Among all mechanisms of control, it is important to distinguish two main categories. The first one includes formal contractual agreements which set out certain rights to the partners. Such agreements concern reporting relationship upwards from one firm to another, formalizing its planning, approval for resource allocation, laying down the procedures to follow within cooperation etc. On the other hand, there is the category involving informal mechanisms. They may comprise the maintenance of regular personal relations with the top managers who take the responsibility of a particular partnership. Moreover, cooperating firms may assign the managers with sufficient time and resources to monitor the progress of common work and to support it with the necessary personal contact. Such informal methods of control over the relationship can have considerable potential enhancing operational control due to the fact that they help shaping the values and relational norms typical of particular cooperation as well as they support mutual understanding between partners (Fryxell, Dooley and Vryza, 2002).

Corporate governance mechanisms should be correlated with the ex ante conditions of a given partnership. Addressing the challenges of managing an effective inter-firm knowledge transfer Mohr and Sengupta (2002, p. 293) highlight the increasing role of corporate governance mechanisms: “as the partner is perceived as having internalization (versus access) intents, as the type of knowledge sought by the focal firm goes from explicit to tacit, and as the duration of the alliance goes from short term to long term risk can be minimized by crafting appropriate g

Trust

Most scholars agree upon the importance of another variable fostering successful collaborative learning that is trust (Gulati, 1995; Adbor, 2002; Hunt, Lambe and Wittman, 2002; Heffernan, 2004; Mellat-Parast and Digman, 2007). The relevant literature proposes different conceptualizations of interfirm trust. Some authors perceive trust rather as predictability, while others emphasize the role of partners’ goodwill. Nevertheless, common to most approaches to define inter-firm trust is the confidence between business partners that the other firm is reliable and that the cooperators will act with a level of integrity while dealing with each other (Morgan and Hunt, 1994a; O’Malley and Tynan, 1997). It means that cooperating firms believe that the other’s actions will be beneficial rather than detrimental to the first partner, even if it cannot be guaranteed. So trust can be said to exist between relationship partners while it involves a high degree of predictability on all sides, that the others will not engage in opportunistic behavior. As highlighted by Child et al. (2005, p. 50), inter-firm trust refers to collaborator’s sufficient confidence in a partner to commit valuable know-how or different resources to a relationship despite the fact that there is always a risk the partner will take advantage of this commitment.

There are three components of inter-firm trust: competency trust, contractual trust as well as goodwill trust. Competency trust refers to the expectation that a relationship partner is able to perform at a set level. The second component – contractual trust – concerns specific oral or written agreements between companies. Goodwill trust refers to partners’ willingness to do more than it is formally expected (Sako, 1992; Sirdeshmukh, Singh and Sabol, 2002). Trust is recognized as the fundamental component for the success of all kinds of inter-firm relationships due to fact that any type of cooperation creates mutual dependence between partners. A significant variable influencing trust between cooperating firms that focus on collaborative learning is convergence over their strategies (Valkokari and Helander, 2007). While the partners of the relationship share common strategic vision, the foundation for common learning is made up in a natural way. If partners set up similar objectives, they obviously present a high level of commitment and do not hesitate to share their knowledge assets. Such a situation frequently results in generating specific knowledge that becomes a partners’ common asset. This, in turn, strengthens mutual trust existing between collaborating companies.

With the regard to the issue of inter-firm trust, it is necessary to point out that trust within any relationship develops gradually as the cooperating companies move from one stage of a relationship to the next one. Combining the approaches by Lewicki and Bunker (1996) and Ford, Gadde, Hakansson and Snehota (2003, p. 49-58) we can state that the trust existing between relationship partners changes its character over time. At the beginning stage of a relationship trust between companies is based on calculations made by them. Then, firms act together and their common outcomes confirm the validity of calculative trust. This situation encourages repeated interactions and partners begin to develop the knowledge base about each other. This is the stage at which partners have already proved to be consistent and reliable and to share their expectations about the relationship. As a result, cooperators prove to be predictable. At that stage partners enter the level of inter-firm trust which now is based on mutual understanding which is called also knowledge-based or cognitive trust (Lewicki and Bunker, 1996, p. 121- 123; Child et al., 2005, p. 56-67). Knowledge-based trust that occurs between cooperators leads to a higher level of their engagement into the relationship, intensive mutual learning towards the specifics of the relationship as well as the investments made by partners and establishing norms that guide conduct. As partners gradually obtain the desired results from the relationship, they begin to identify with each other’s goals and interests. At this stage of relationship, the development of mutual trust based on personal identification is likely to occur. That is the highest level of relationship trust, which partially emerges from the issues relating to goodwill and competency, recognized by each partner at earlier stages of the relationship development process.

Communication

Being aware of inter-firm trust importance, it is necessary to focus on its relations with the process of communication between collaborating firms. In line with relevant literature, the communication system that exists within a relationship is another significant condition fostering successful collaborative learning (Morgan and Hunt, 1994b; Adbor, 2002; Hunt et al., 2002).

According to most approaches, communication is recognized as the foundation process that facilitates the inter-firm relationship development and its ongoing maintenance. It results from the fact that the process of reciprocal communication creates shared meanings between partnering enterprises. Consequently, the predictability concerning partners’ behavior arises from these shared meanings. Moreover, it has been recognized that also partners’ good will appears as the result of their participation in the communication process whereby shared meanings are created (Hardy, Philips and Lawrence, 2000, p. 69).

Given the fact that inter-firm trust grows out of a communication system, communication between collaborating enterprises may be seen as a kind of “glue” that holds the partners of the relationship together. It is not possible to build a strong and successful inter-firm relationship aimed at collaborative learning without the knowledge and understanding of how communication influences the behaviors of cooperating partners.

Communication within the relationship focusing on common learning should be an ongoing dialogue. In close inter-firm relationships it is all about a dialogue where people and organizations learn from each other, change and adapt. The dialogue concept incorporates the idea that between cooperating firms there are exchanges rich in information and capable of creating new knowledge (Donaldson and O’Toole, 2007, p. 149-150).

In the framework of inter-firm communication, two most common measures are distinguished. The first measure is associated with the mechanistic approach. The mechanical facets of communication include: the message content, the channel mode (formal and informal), feedback and frequency. On the other hand, the behavioral measures of communication between cooperating partners involve communication quality, information and knowledge sharing and participation (Donaldson and O’Toole, 2007, p. 150-151). According to Cousins, Lawnson and Squire (2008, p. 244), the communication performance measures are the following: effectiveness of communication, information exchange, information quality and timeliness and the level of feedback from the relationship partner.

As far as communication quality is concerned, it is necessary to focus on accuracy, adequacy, timeliness, completeness and credibility of shared information. It is indisputable that the quality and intensity of the information shared by partners highly influence the strength of the relationship. As highlighted by Mohr and Spekman, the higher the quality of information sharing is and the more intense it is, the more likely is that a relationship will be stable and developing (Mohr and Spekman, 1994). Also, cooperators’ participation in several aspects of the relationship communication system improves the closeness of the partnership and strengthens partners’ mutual trust.

Here it is important to say that most authors point out that the quality as well as quantity (frequency) of communication between cooperating firms on one hand stimulate the emergence of inter-firm trust, because due to mutual understanding it makes it easier to predict each other’s behavior. But on the other hand, to flourish, communication requires the foundation that is a particular level of inter-firm trust (Sako, 1992, p. 126-133; Borch, 1994, p. 113-135; Sydow, 2000, p. 48).

While discussing the nature and the role of communication within interfirm relationships the present-day approaches concentrate also on the issue of conflict resolution. Conflicts between partnering companies may occur as a natural result of intensive cooperation and desire to accomplish their own goals. The ability to handle such conflicts in an efficient and effective way is needed to maintain successful cooperation and collaborative learning. The system of conflict management should be involved into the communication system set up for a particular relationship. It should enable managers and employees of partnering firms to gather information, understand the context and then participate in the decision making process enhancing their capacity to deal with a conflict before it escalates (Zineldin, 2004, p. 780-789; Parung and Bititci, 2006, p. 125; Chin, Chan and Lam, 2008, p. 445).

Concluding, the communication system that enables the effective sharing of information needed for the relationship goals implementation, is an important factor fostering partners’ trust which sometimes is conceptualized as a communicative, sense-making process that bridges disparate groups (Zuker, 1986; Sabel, 1993). It has been recognized that such communication systems significantly reduce the level of uncertainty perceived by cooperators, especially in the new situation which is the establishing of an inter-firm relationship aimed at collaborative learning.

Commitment

Collaborators’ commitment is defined as their conviction that the relationship is beneficial for them so they are eager to undertake different activities in order to sustain it and assure the stability and efficiency of a relationship (Barry, Dion and Johnson, 2008, p. 119). While discussing the nature of relationship partners’ commitment, it seems necessary to point out three dimensions of commitment which are typical of inter-firm learning relationships. Those dimensions involve operational commitment, information commitment and investment commitment. The first of above mentioned, operational commitment, refers to cooperating companies’ shares in the common venture. It is indisputable that the more investments the partners make, the more attention they will pay to the usage of invested resources as well as to the cooperation outcomes. Information commitment is the second dimension of partners’ commitment. In general, it concerns the communication between cooperators. In particular it refers to the type, frequency, forms of interfirm communication and the way that partners apply gathered information. What is significant, practitioners underlie that this dimension of partners’ commitment refers mainly to the honesty while sharing information with a cooperator. Due to its character, the information dimension of commitment appears as an essential condition for the development of knowledge-creating relationships. The third of above mentioned, that is the investment dimension of commitment, concerns resources allocated by relationship partners (Czakon, 2007, p. 82-83).

Among pertinent issues regarding the commitment within a business relationship, there is a necessity for underlying the importance of mutual trust between partners. According to the research conducted by Walter, Mueller and Helfert on a group of 230 inter-firm relationships, trust as well as relationship value are powerful predictors of relationship partner’s commitment (Walter, Mueller and Helfert, 2014). If cooperating firms trust each other, they show a higher level of eagerness to share their strategic resources, such as knowledge. Moreover, if the relationship is characterized by a high level of mutual trust, the partners find any investment they make in cooperation as being less risky. What is more, while the commitment of the firms that have established a particular relationship increases over time, it restricts the risk of partners’ opportunistic behaviors. Such a positive change results from the fact that cooperating companies have already allocated some valuable resources to set up a cooperation and they steer clear of the loses in the case of the relationship breakdown.

A MODEL OF THE CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS FOR COLLABORATIVE LEARNING

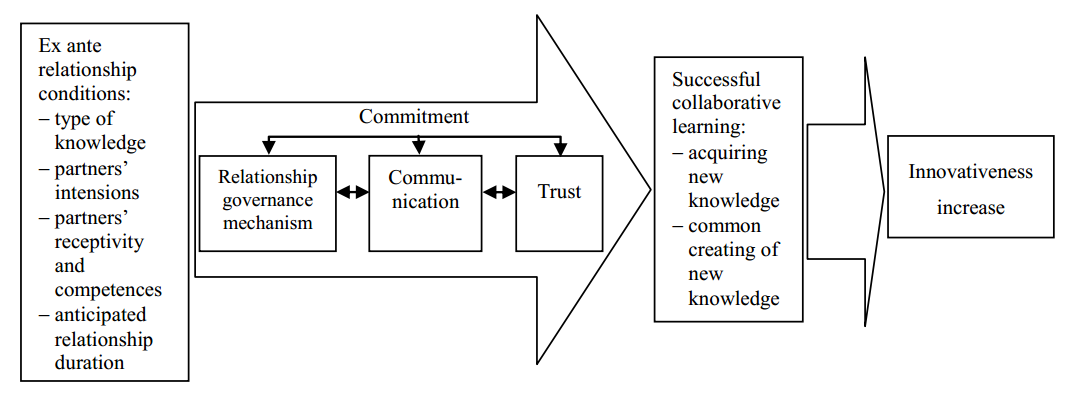

We propose a model (Figure 1) providing an insight into the interrelations among critical factors for successful collaborative learning occurring in interfirm relationships. The findings from the literature analysis enabled us to identify the building blocks of the model. We developed the model around the classification of inter-firm learning types and their antecedents identified by Child et al. (2005) and we have made attempts to integrate the extant knowledge in the area of study. We were especially inspired by the streams of literature on absorptive capacity (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Zahra and George, 2002; Todorova and Durisin, 2007; Sun and Anderson, 2010) and the elements of inter-firm positive potential such as: relationship governance mechanisms (Mohr and Sengupta, 2002; Child et al., 2005) trust (Hardy et al., 2000; Child, 2001; Heffernan, 2004), inter-firm communication (Chin et al., 2008; Cousins et al., 2008) and commitment (Barry et al., 2008; Chin et al., 2008). In our approach we purposely separated learning prerequisites from learning enhancers. We assume that factors which determine decisions to establish inter-firm learning partnership are different from those which motivate partners to sustain their relationship.

In our model, success in collaborative learning is understood as accomplishing the agreed relationship goals that partners set up for a particular relationship in quantifiable terms (Jap, 2001; Child et al., 2005, p. 194). Consequently, this should result in the increase in cooperating firms’ innovativeness. Successful collaborative learning includes both acquiring knowledge that is completely new to a firm or/and common creating of new knowledge. Such knowledge becomes a valuable strategic asset for both cooperating companies. Moreover, successful collaborative learning means that relationship participants maximize desired learning while at the same time minimize undesired learning. This aspect seems to be of significant importance due to the dyadic nature of inter-firm learning. To be successful and therefore satisfied with the learning oriented relationship, cooperating companies have to include protection against partner’s accessing their own propriety information.

The starting point for the model is composed of ex ante relationship conditions that include partners’ intentions, their receptivity to new knowledge as well as their competences in knowledge assimilation and anticipated relationship duration. As the critical factors determining the success of inter-firm cooperation focused on creating knowledge assets the model points out specific governance mechanisms designed to coordinate and control relationships, mutual trust between relationship partners, an effective communication system within a relationship and the development of the relationship. All aforementioned variables are included into another significant factor that is relationship partners’ commitment.

Ex ante relationship conditions are necessary to establish the minimum level of calculative trust in order to enter into such an inter-firm learning relationship (cf. Child, 2000; Child, 2001). The nature and importance of trust has been discussed earlier in the paper. It is necessary to note that trust between cooperating enterprises creates the foundation for effective information and knowledge exchange. If partners trust each other, they are more willing to deliver appropriate and valuable information and knowledge that are needed for cooperation. This exchange in turn increases the level of mutual trust between partners. Moreover, trust evolves and changes its character, from calculative to cognitive. Another critical factor for successful collaborative learning presented in the model is setting up proper governance mechanisms for a particular relationship. A high degree of trust, combined with an effective and satisfactory communication system as well as proper governance mechanisms entail a high degree of partners’ good will and commitment to common activities and objectives.

The core issue for the proposed model is combining the above described elements and understanding interrelations that exist among them. It is indisputable that a high level of mutual trust, communication based on this trust, control procedures as well as partners’ commitment are all necessary to share valuable strategic assets, e.g. knowledge. Therefore the combination of those variables fosters the process of collaborative learning. What is also of significant importance, the presented model is of dynamic character that means the state of its elements is changing over time. The knowledge concerning the significance and the impact of above discussed factors on the success in collaborative learning enables managers of cooperating firms to create intentionally the conditions fostering the increase both in enterprise knowledge bases and their ability to create innovations.

We acknowledge the fact that developing a model of successful collaborative learning for company innovativeness is a very ambitious and challenging aim. Recognizing the significant role of absorptive capacity for inter-firm learning, the challenges related to developing such a capacity should be considered. Overlooking the potential of new knowledge or being unable to understand it is one of the risks. Another problem is the failure to distinguish between knowledge which can be easily attached to existing knowledge structures (knowledge assimilation) from knowledge which requires the change of organizational knowledge structures in order to enable knowledge transformation. Moreover, contingent factors such as social integration mechanisms, regimes of appropriability and power relationships should be taken into account. Finally, the effectiveness of the feedback loop between absorptive capacity and the company knowledge base needs to be considered (cf. Todorova and Durisin, 2007). The issues discussed above are only the example of the variety of barriers and challenges connected to the building blocks of a model of critical success factors for collaborative learning. Being aware of these challenges we recognize the need for further studies in the area in order to investigate thoroughly the aforementioned challenges and to apply them to test our model.

CONCLUSION

Summing up, we assess that all the paper objectives have been reached. The problems of the structural conflict between competition and collaboration occurring in inter-firm learning partnerships have been analyzed. Inter-firm learning relationships have been defined and characterized. Then, the ex ante conditions of successful collaborative learning and the intra-organizational enhancers of inter-firm learning processes have been identified and studied. Finally, a model of the critical success factors for collaborative learning has been developed.

Nevertheless, we are aware that the identified critical success factors for collaborative learning require further research. First of all, the barriers and challenges related to the components of the model need to be studied thoroughly. Then, in our opinion, the relationships between ex ante conditions and collaborative learning enhancers are the issue of predominant importance to be investigated. Moreover, the cohesion of the aforementioned constructs and the mutual relationships between their elements need to be explored. Further research activities within the field should be aimed at measuring the strength of these relationships and identifying cause-effect relations in order to provide managers with recommendations necessary to build up the potentials of their companies to participate successfully in inter-firm learning partnerships.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and valuable recommendations for the improvement of the paper draft. Our special thanks go to Associate Professor James Karlsen for his mentorship during the reviewing process.

References

- Adbor, H. (2002). Competitive Success in an Age of Alliance Capitalism: How Do Firm-specific Factors Affect Behavior in Strategic Alliances. Advances in Competitiveness Research, 10(1), 71-100.

- Amit, R., Schoemaker, P.J.H. (1993). Strategic Assets and Organisational Rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1), 33-46.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 106-112.

- Barry, J.M., Dion, P. Johnson, W. (2008). A Cross-cultural Examination of Relationship Strength in B2B Services. Journal of Services Marketing, 22(2), 114-135.

- Berdrow, I., Lane, H.W. (2003). International Joint Ventures: Creating Value Through Successful Knowledge Management. Journal of World Business, 38(1), 15-30.

- Beamish, P.W., Berdrow, I. (2003). Learning from IJVs: The Unintended Outcome. Long Range Planning, 36(3), 285-303.

- Borch, O.J. (1994). The Process of Relational Contracting: Developing Trust-Based Strategic Alliances Among Small Business Enterprises. In: I. Shrivastava, P.J. Dutton, A. Huff (Eds.), Advances in Strategic Management (pp. 113-135), Greenwich (Connecticut): JAI Press Inc.

- Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E. (Eds.) (2003), Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline, Berett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco.

- Chang, Y., Gong, Y., Peng, M.W. (2012). Expatriate Knowledge Transfer, Subsidiary Absorptive Capacity and Subsidiary Performance. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 927-948.

- Chesbrough, H. (2008). Open Innovation: A New Paradigm for Understanding Industrial Innovation. In: H. Chesbrough, W. Vanhaverbeke, J. West (Eds.), Open Innovation. Researching a New Paradigm for Understanding Industrial Innovation (pp.1-12), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Child, J. (2000), Trust and International Strategic Alliances: The Case of SinoForeign Joint Ventures. In: Ch. Lane, R. Bachmann (Eds.), Trust Within and Between Organizations: Conceptual Issues and Empirical Applications (pp. 241-271). Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Child, J. (2001), Trust-The Fundamental Bond in Global Collaboration, Organizational Dynamics, 29(4), 274-288.

- Child, J., Faulkner, D., Tallman, S.B. (2005). Cooperative Strategy: Managing Alliances, Networks and Joint Ventures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Child, J., Markóczy L. (1993). Host Country Managerial Behavior and Learning in Chinese and Hungarian Joint Ventures. Journal of Management Studies, 30, 611-631.

- Chin, K.S., Chan, B.L., Lam P.K. (2008). Identifying and Prioritizing Critical Success Factors for Coopetition Strategy. Industrial Management &Data Systems, 108(4), 437-454.

- Cohen, W.M, Levinthal, D.A. (1990). Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 128- 152.

- Cousins, P.D., Lawnson, B., Squire, B. (2008). Performance Measurement in Strategic Buyer-Supplier Relationships: The Mediating Role of Socialization Mechanisms. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 28(3), 238-258.

- Cowan, R. (2007). Network Models of Innovation and Knowledge Diffusion. In: S. Breschi, F. Malerba (Eds.), Clusters, Networks and Innovation (pp. 29-49), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Crossan, M.M, Lane, H.W., White, R.E. (1999). An Organizational Learning Framework: From Intuition to Institution. Academy of Management Review, 24, 522-537.

- Cummings, J.L., Teng, B-S. (2003). Transferring R&D Knowledge: The Key Factors Affecting Knowledge Transfer Success. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 20, 39-68.

- Czakon, W. (2007). Dynamika więzi międzyorganizacyjnych przedsiębiorstwa. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej im. Karola Adamieckiego.

- Donaldson, B., O’Toole, T. (2007). Strategic Market Relationships. Chichester: John Wiley &Sons, Ltd.

- Easton, G. (1992), Industrial Networks: A Review. In: B. Axelsson, G. Easton (Eds.), Industrial Networks: A New View of Reality (pp. 3-27), London: Routledge.

- Fiol, C.M., Lyles, M.A. (1985). Organizational Learning. The Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 803-813.

- Ford, D., Gadde, L.E. Hakansson, H., Snehota, I. (2003). Managing Business Relationships. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Fryxell, G.E., Dooley, R.S., Vryza, M. (2002). After the Ink Dries: The Interaction of Trust and Control in US-based International Joint Ventures. Journal of Management Studies, 39(6), 868-869.

- Gaule, A. (2006). Open Innovation in Action: How to be Strategic in the Search for New Sources of Value, London: H-I Network.

- Gourlay, S. (2003). The SECI Model of Knowledge Creation: Some Empirical Shortcomings, 4th European Conference on Knowledge Management, Oxford, England. Retrieved from http://eprints.kingston.ac.uk/2291/ (02 Jun. 2014).

- Gourlay, S. (2006). Conceptualizing Knowledge Creation: A Critique of Nonaka’s Theory. Journal of Management Studies, 43(7), 1415-1436.

- Gulati, R. (1995). Does Familiarity Breed Trust? The Implications of Repeated Ties for Contractual Choice in Alliances. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 85-112.

- Gulati, R. (2007). Managing Network Resources: Alliances, Affiliations and Other Relational Assets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hamel, G. (1991). Competition for Competence and Inter-partner Learning within International Strategic Alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 12(S1), 83-103.

- Hardy, C., Philips, N., Lawrence, T. (2000). Distinguishing Trust and Power in Interorganizational Relations: Forms and Facades of Trust. In: Ch. Lane, R. Bachmann (Eds.), Trust Within and Between Organizations: Conceptual Issues and Empirical Applications (pp. 65-87), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heffernan, T. (2004). Trust Formation in Cross-cultural Business-to-Business Relationships. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 7(2), 114-125.

- Hunt, S.D., Lambe, C.J., Wittman, C.M. (2002). A Theory and Model of Business Alliance Success. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 1(1), 17-35.

- Inpken, A.C. (1995). The Management of International Joint Ventures: An Organizational Learning Perspective. London: Routledge.

- Inpken, A.C. (2002). Learning, Knowledge Management and Strategic Alliances: So Many Studies, So Many Unanswered Questions. In: J.F. Contractor and P. Lorange (Eds.), Cooperative Strategies and Alliances (pp. 267-289). Amsterdam: Pergamon.

- Jap, S. (2001), “Pie sharing” in Complex Collaboration Context. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(1), 86-99.

- Jashapara, A. (2004). Knowledge Management: An Integrated Approach. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

- Johanson, J., Mattsson, L-G. (1985). Marketing Investments and Market Investments in Industrial Networks, International Journal of Research in Marketing, 2(3), 185-195.

- Kastalli, I.V., Neely A. (2013). Collaborate to Innovate: How Business Ecosystems Unleash Business Value. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. Cambridge Service Alliance. Retrieved from: www.cambridgeservicealliance.org (05 Sep. 2014).

- King, D.R., Covin, J.G., Hegarty, W.H. (2003). Complementary Resources and the Exploitation of Technological Innovations. Journal of Management, 29(4), 589-606.

- Lawson, B., Potter, A. (2012). Determinants of Knowledge Transfer in Inter-firm New Product Development Projects. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 32(10), 1228-1247.

- Lewicki, R.J., Bunker, B.B. (1996). Developing and Maintaining Trust in Work Relationships. In: R.M. Kramer, T.R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research (pp. 114-149). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc.

- Makinen, H. (2002). Intra-firm and Inter-firm Learning in the Context of Startup Companies, Entrepreneurship and Innovation, February, 35-43.

- Malhotra, D., Lumineau F. (2011). Trust and Collaboration in the Aftermath of Conflict: The Effects of Contract Structure. Academy of Management Journal, 54(5), 981-998.

- March, J.G. (1991). Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organization Science, 2, 71-87.

- Martinkenaite, I. (2011). Antecedents and Consequences of Interorganizational Knowledge Transfer: Emerging Themes and Openings for Further Research. Baltic Journal of Management, 6(1), 53-70.

- Mathews, J. (1996). Organizational Foundations of Economic Learning, Human Systems Management, 15(2), 113-124.

- Mellat-Parast, M., Digman, L.A. (2007). A Framework for Quality Management Practices in Strategic Alliances. Management Decision, 45(4), 802-818.

- Mitra, J. (2000). Making Connections: Innovation and Collective Learning in Small Business. Education+Training, 42(4/5), 228-237.

- Mohannak, K. (2007). Innovation Networks and Capability Building in the Australian High-technology SMEs. European Journal of Innovation Management, 10(2), 236-251.

- Mohr, J.J., Sengupta, S. (2002). Managing the Paradox of Inter-firm Learning: The Role of Governance Mechanisms. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 17(4), 282-301.

- Mohr, J., Spekman, R. (1994). Characteristics of Partnership Success: Partnership Attributes, Communication Behaviour and Conflict Resolution Techniques. Strategic Management Journal, 15(2), 135-152.

- Morgan, R.M., Hunt, S.D. (1994a). Relationship Marketing in the Era of Network Competition. Marketing Management, 5, 20-38.

- Morgan, R.M., Hunt, S.D. (1994b). The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. Journal of Marketing, July, 58(3), 20-38.

- Mu, J., Peng, G., Love, E. (2008). Interfirm Networks, Social Capital and Knowledge Flow. Journal of Knowledge Management, 12(4), 86-100.

- Nag, R., Giola, D.A. (2012). From Common to Uncommon Knowledge: Foundations of Firm-specific Use of Knowledge as a Resource. Academy of Management Journal, 55(2), 421-457.

- Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H. (1995). The Knowledge-Creating Company. New York: Oxford University Press.

- O’Malley, L., Tynan, C. (1997). A Reappraisal of the Relationship Marketing Construct of Commitment and Trust. In: T. Meenaghan (Ed.), New and Evolving Paradigms: The Emerging Future of Marketing (pp. 486-503). Three American Marketing Association Special Conferences

- Palakshappa, N., Gordon, M.E. (2007). Collaborative Business Relationships: Helping Firms to Acquire Skills and Economies to Prosper. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 14(2), 264-279.

- Parung, J., Bititci U.S. (2006). A Conceptual Metric for Managing Collaborative Networks, Journal of Modelling in Management, 1(2), 111-136.

- Perks, H. (2004). Exploring Processes of Resource Exchange and Co-creation in Strategic Partnering for New Product Development. International Journal of Innovation Management, 8(1), 37-61.

- Powell, T.H. (2007). A Critical Review of Nonaka’s SECI Framework. Paper presented at Advanced Doctoral Seminar, 16thEDAMBA Summer Academy, Soreze, France. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/714629/A_ Critical_Review_of_Nonakas_SECI_Framework (02 Jun 2014).

- Prahalad, C.K., Hamel, G. (1990). The Core Competence of the Corporation. Harvard Business Review, May–June, 76-88.

- Saarenketo, S., Kuivalainen, O., Kylaheiko, K., Puumalainen, K. (2004). Dynamic Knowledge-related Learning Processes in Internationalizing High-technology SMEs. International Journal of Production Economics, 89, 363-378.

- Sabel, C.F. (1993). Studies Trust: Building New Forms of Cooperation in a Volatile Economy. Human Relations, 4( 9), 1133-1170.

- Sako, M. (1992). Price, Quality and Trust: Inter-Firm Relations in Britain and Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sirdeshmukh, D., Singh, J., Sabol, B. (2002). Customer Trust, Value and Loyalty in Relational Exchanges. Journal of Marketing, 66(1), 15-37.

- Simonin, B.L. (1997). The Importance of Collaborative Know-how: An Empirical Test of the Learning Organization. Academy of Management Journal, 40(5), 1150-1174.

- Simonin, B.L. (2004). An Empirical Investigation of the Process of Knowledge Transfer in International Strategic Alliances. Journal of International Business Studies, 35, 407-427.

- Stankiewicz, M.J. (Ed.) (1999), Budowanie potencjału konkurencyjności przedsiębiorstwa: Stan i kierunki rozwoju potencjału konkurencyjności polskich przedsiębiorstw w kontekście dostosowania gospodarki do wymogów Unii Europejskiej, Toruń: Dom Organizatora TNOiK.

- Stankiewicz, M.J. (2002), Konkurencyjność przedsiębiorstw: Budowanie konkurencyjności przedsiębiorstwa w warunkach globalizacji, Toruń: Dom Organizatora TNOiK.

- Stankiewicz, M.J. (Ed.) (2010), Pozytywny Potencjał Organizacji: Wstęp do użytecznej teorii zarządzania, Toruń: Dom Organizatora TNOiK.

- Stankiewicz, M.J. (Ed.) 2013, Positive Management: Managing the Key Areas of Positive Organisational Potential for Company Success, Toruń: Dom Organizatora TNOiK.

- Stańczyk-Hugiet, E. (2013). Interfirm Relationships: Evolutionary Perspective. Ekonomika, 92(3), 59-73.

- Sudolska, A. (2011). Uwarunkowania budowania relacji proinnowacyjnych przez przedsiębiorstwa w Polsce. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UMK.

- Sun, P.Y.T., Anderson, M.H. (2010), An Examination of the Relationship Between Absorptive Capacity and Organisational Learning and a Proposed Integration. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(2), 130- 150. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00256x.

- Sydow, J. (2000). Understanding the Constitution of Interorganizational Trust. In: Ch. Lane, R. Bachmann (Eds.), Trust Within and Between Organizations: Conceptual Issues and Empirical Applications (pp. 31-63), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Teece, D.J. (1998). Capturing Value from Knowledge Assets: The New Economy, Markets for Know-How, and Intangible Assets. California Management Review, 40(3), 55-79.

- Todorova, G., Durisin, B. (2007), Absorptive Capacity: A Valuing of Reconceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 774-786.

- Trott, P. (2008). Innovation Management and New Product Development. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

- Valkokari, K., Helander, N. (2007). Knowledge Management in Different Types of Strategic SME Networks. Management Research News, 30(8), 597- 608.

- Vanhaverbeke, W. (2008). The Interorganizational Context of Open Innovation. In: H. Chesbrough, W. Vanhaverbeke, J. West (Eds.), Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm for Understanding Industrial Innovation (pp. 205-219), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Walter, A., Mueller T.A., Helfert, G. (2014). The Impact of Satisfaction, Trust and Relationship Value on Commitment: Theoretical Considerations and Empirical Results. Retrived from: www.impgroup.org (23 Jun. 2014).

- Wang, Ch., Rodan, S., Fruin, M., Xu, X. (2014). Knowledge Networks, Collaboration Networks and Exploratory Innovation. Academy of Management Journal, 57(2), 484-514.

- Wu, W-Y., Wu, Y-J., Lo, Y-J. (2004). The Impact of Governance Mechanisms on Interfirm Learning and Relationship Performance. Proceedings of the Asia Pacific Management Conference, 447-462. Retrieved from: http:// www.kyu.edu.tw/93/epaperv7/109.pdf (07 Sep. 2014).

- Yang, H., Lin, Z., Peng, M.W. (2011). Behind Acquisitions of Alliance Partners: Exploratory Learning and Network Embeddedness. Academy of Management Journal, 54(5), 1069-1080.

- Zahra, S.A., George, G. (2002), Absorptive Capacity: A Review, Reconceptualization and Extention. Academy of Management Review, 27, 185-203.

- Zineldin, M. (2004). Coopetition: The Organization of the Future. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 22(7), 780-789.

- Zuker, L.G. (1986). Production of Trust: Institutional Sources of Economic Structure. In: B.M. Staw, L.L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behaviour, 8, 53-111.

Biographical note

Agata Sudolska, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Economic Sciences and Management, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń. Her area of interests and research activities encompasses the issues of the process of creating innovations as well as managing inter-firm relationships and networks, in particular with the focus on knowledge exchange and collaborative learning.

Andrzej Lis, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Economic Sciences and Management, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń and a staff officer of the Doctrine and Training Centre of the Polish Armed Forces, Bydgoszcz. His area of research activity encompasses the issues of knowledge management, change management, defence industry and military logistics, whereas the main research interest is focused on Lessons Learned processes.