Kati Tikkamäki, D.Ed., University of Tampere, School of Social Sciences and Humanities, 33014 University of Tampere, Finland. E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Päivi Heikkilä, MSc, VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, P.O. Box 1000, FI-02044 VTT, Finland. E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Mari Ainasoja, MSc Econ. and Bus. Adm., School of Information Sciences, University of Tampere, FI-33014 University of Tampere, Finland. E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Abstract

While heavy stress loads seem an unavoidable aspect of entrepreneurship, the positive side of stress (often referred to as ‘eustress’) remains a neglected area of research. This paper contributes to entrepreneurship research by linking the research streams of eustress and reflective practice. As a tool for analysing and developing thoughts and actions, reflective practice plays an important role in the interpretative work essential to positive stress experiences. Following an overview of approaches to stress at work, eustress and reflective practice, the paper explores how entrepreneurs experience the role of positive stress and reflective practice in their work and describes the reflective tools utilized by entrepreneurs in promoting eustress. The research process was designed to support reflective dialogue among the 21 Finnish entrepreneurs from different fields who participated in the study, with results based mainly on qualitative interviews. Nine of the interviewed entrepreneurs also kept a positive stress diary, including a three-day physiological measurement analysing their heartbeat variability. The findings suggest that positive stress and reflective practice are intertwined in the experiences of entrepreneurs and illustrate the role of reflective practice as a crucial toolset for promoting positive stress, comprising six reflective tools: studying oneself, changing one’s point of view, putting things into perspective, harnessing a feeling of trust, regulating resources and engaging in dialogue. Individual reflective capabilities vary, and a theory-driven division of reflective practice into individual, social and contextual dimensions is considered useful in understanding those differences. The research offers a starting point for exploring how eustress and reflective practice affect the well-being of entrepreneurs.

Keywords: eustress, positive stress, reflective practice, entrepreneurs.

Introduction

Stress can be regarded as one of the darker aspects of entrepreneurial leadership (Kuratko, 2007). Entrepreneurs are commonly assumed to be subject to stress because of their heavy workloads, risk in their business activities (Palmer, 1971), a higher-than-average need for achievement (Langan-Fox & Roth, 1995), long working hours and a self-established role in the organisation (Harris, Saltstone & Fraboni, 1999). The fact that business survival rests on the entrepreneur’s shoulders is likely to be a source of pressure, and high stress tolerance is seen as one of the strengths of the entrepreneurial personality (Frese, 2009). Rahim (1996) found that entrepreneurs reported a higher internal locus of control than managers and were therefore in a position to manage stress more effectively. Entrepreneurs may also have a special attitude to stress. According to a recent study, selfemployed people experience greater stress than employees, but despite negative health effects, they also experience a positive effect of stress in terms of their income (Cardon & Patel, 2015).

Entrepreneurs in particular must find a balance between work and life outside work, and between productivity and recovery. In this regard, work and non-work can be seen as distinct domains or as mutual domains that influence, compensate, facilitate or conflict. Here, ‘balance’ is understood as active doing—bringing into equilibrium—in which human beings are seen to be able to manage balance in their lives (Guest, 2002). On that basis, it would seem useful for each individual to find their own interpretation of that balance through reflective practice. Many entrepreneurs differ from employees in their perspective on work-life balance—for instance, in relation to autonomy and passion for work, which are common characteristics of entrepreneurs (Frese, 2009).

The present study focuses on the positive side of stress (eustress) and on reflective practice among entrepreneurs; the aim is to illuminate the reflective skills and resources used by entrepreneurs to promote positive stress in their lives. This positive side of stress has to date attracted less research interest than negative stress. Although the beneficial aspects of stress were recognized several decades ago (e.g. Lazarus, 1966; Selye, 1974), they have been neglected in recent research; in particular, a number of authors have identified a need for further research on eustress in work-life settings (Hargrove, Nelson & Cooper, 2013; Le Fevre, Matheny & Kolt, 2003; Simmons & Nelson, 2007). Research suggests that both positive and negative affect may influence many aspects of work in terms of change-oriented behaviour (Amabile, Barsade, Mueller & Staw, 2005; Anderson, De Dreu, & Nijstad, 2004; George & Zhou, 2002); for example, distress has been found to hinder creativity and innovativeness (Amabile, Barsade, Mueller & Staw, 2005). Given the widely accepted role of stress in entrepreneurship, a better understanding seems especially important in that context.

The key factor in eustress is that responses to stressors depend on one’s perception of the situation and can therefore be interpreted either positively or negatively (Hargrove et al., 2013; Lazarus, 1966; Simmons & Nelson, 2007). To the extent that reflection contributes to this interpretation, reflective practice is potentially a tool for entrepreneurs seeking to harness the benefits of eustress. However, there is a lack of empirical research on the positive stress experiences of entrepreneurs in general and only a few studies on the relationship between stress and reflection. This paper takes a first step towards bridging this gap by exploring entrepreneurs’ descriptions of positive stress and reflective practice in their everyday experiences. Our research questions were as follows.

How do entrepreneurs experience the role of positive stress and reflective practice in their work?

Do entrepreneurs describe reflective practices in connection with their positive stress experiences? If so, what kinds of tools for reflective practice do they utilize to exploit positive stress?

Literature review

Approaches to stress at work: towards a more positive and holistic approach

Research on work stress has been guided by a number of theories, variously emphasising, for example, the relationship between job demands and job control (demand-control model) (Karasek & Theorell, 1990); the imbalance between perceived efforts and rewards at work (effort-reward imbalance model) (Siegrist, 1996) or the processes of appraisal and coping (cognitive stress theory) (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

The view of stress adopted here is based mainly on transactional theories. Lazarus & Folkman’s (1984) cognitive theory distinguishes between primary and secondary appraisal processes; first, a situation is evaluated in terms of perceived potential risk, and secondary appraisal then assesses potential actions and ways of coping. Cox (1978) emphasised the ongoing and individual nature of the appraisal process; his model also included outcome and feedback stages of coping. This transactional view is useful in exploring stress experiences and reflective practice, as the interpretation of stressors is seen as a key factor in explaining the emotions and reactions associated with the stress experience. The focus of the present research is not the appraisal process itself but a holistic exploration of individual reflections on experience.

While transactional theories acknowledge the role cognitive and emotional processes in experiences of stress, they have tended to focus mainly on stress as a negative phenomenon. When coping skills are inadequate, stress induces negative feelings and reduces work performance. According to one definition of distress, it "occurs when an individual perceives that the demands of an external situation are beyond his or her perceived ability to cope with them" (Lazarus, 1966). However, more recent approaches to stress also recognise the positive impacts that job characteristics and conditions may have on wellbeing. The job demands-resources (JDR) model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004) is based on the work of Karasek and Siegrist but approaches stress from a wider perspective, in which job demands and resources are seen as key conditions that may have a negative impact on health but may also increase work motivation. Job demands might include workload, task complexity and role ambiguity, all of which require considerably energy. Job resources (aspects of the job that may have motivational potential and help to tackle demands) include. autonomy, opportunities for growth and performance feedback. According to the JDR model, when sufficient job resources are available, job demands may boost work engagement and performance. Job crafting, redesigning and reimagining in personally meaningful ways offer possibilities for optimizing job demands and resources (Bakker, 2015).

Although many theories also acknowledge the positive side of stress, only a few have emphasised this aspect or studied it empirically. One exception is Simmons and Nelson’s (2007) holistic model of stress, which can be seen as an example of positive psychology (‘a science of positive subjective experience’), questioning the focus on disease and emphasizing human strengths and health as the presence of positive states (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). The holistic model of stress includes both distress (negative) and eustress (positive), characterising these as separate and distinct responses. Simmons and Nelson (2007) propose that appraisal of any encounter can produce positive or negative meanings; they focus on the positive aspects, exploring how people may also cope by ‘savouring the positive’ and so developing resources for managing demanding encounters.

The idea that stress experiences can be divided into the harmful (distress) and the beneficial (eustress) is not new (Selye, 1974), but the limited existing research means that the phenomenon has not been clearly conceptualized. Current understanding emphasises the interpretation of stressors; responses to stressors depend on one’s perception of the situation and can therefore be interpreted either positively, negatively or as a combination of the two (Hargrove et al., 2013). In addition, positive affect can have a buffering effect on (di)stress. In a recent empirical study of stress among self-employed people, positive affect was found to mitigate the negative effects of stress on physical health and to accentuate the positive effect on personal income. This may also cause negative stress to seem ‘worth it’ for this occupational group (Cardon & Patel, 2015).

Eustress relates to more familiar positive work-related concepts such as flow experience and work engagement. The experience of eustress can culminate in flow, which has been called ‘the epitome of eustress’ (Hargrove et al., 2013). In flow, the individual is fully focused on and extremely motivated by the work task, to the extent that nothing else seems to matter (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Work engagement is defined as a positive, relatively stable, affective-motivational state of fulfilment at work (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá & Bakker, 2002). As work engagement is a more stable state than eustress, this may contribute to a greater likelihood of experiencing eustress.

Based on the above evidence, rather than minimising the negative impacts of stress, we seek to acknowledge its potential positive effects on entrepreneurs’ wellbeing. Perception and interpretation both play a crucial role in stress reactions, serving to define when these are experienced as either debilitating or empowering and setting the context for reflective practice.

Reflective practice: interpreting and promoting eustress

“Reflection is an active and purposeful process of exploration and discovery, often leading to unexpected outcomes. It is the bridge between experience and learning, involving both cognition and feelings” (Boud, Keogh & Walker, 1985).

There is broad consensus among learning theorists that reflection is at the core of adult learning and professional growth, transformation and empowerment (Boud et al., 1985; Dewey, 1938; Kolb, 1984). Depending on the grounding ontological and epistemological premises, reflection has been variously defined. Often visualized as a bridge between experience and learning (Boud et al., 1985), reflection is a meta-competence—a competency that enables individuals to monitor and/or develop other competencies (Cheetham & Chivers, 1998), referring to the ability to ‘learn to learn’ and to think ‘outside the box’. In the workplace, reflection is a powerful tool for problem solving, making tacit knowledge explicit and examining practice and routines (Argyris & Schön, 1996; Boud, Cressey & Dogherty, 2006; Schön, 1983). Such conscious processes allow us to make decisions that are active and aware about our learning experiences by evaluating them and making choices about what we will or will not to do (Boud, Keogh & Walker, 2002).

Reflection is often related to an individual’s cognitive processes, as in becoming aware of and evaluating, questioning and criticising experiences, assumptions, beliefs, practices and emotions. It relates to skills of selfregulation, self-monitoring (Zimmerman, 1995) and self-directedness. At the individual level, reflection seems to resonate well with cognitive stress theory’s concept of primary appraisal, in which one considers the significance of an encounter and evaluates it in terms of its personal meaning (Lazarus, 2001). Reflection has also been discussed as a process of seeking understanding (Mezirow, 1981; Schön, 1983; Raelin, 2001) through selfdialogue (Hilden & Tikkamäki, 2013; Tsang, 2007), in which self-talk plays a crucial role. Inner speech provides self-generated feedback that can affect individual performance (Neck, Neck, Manz & Godwin, 1999).

Beyond individual reflection, other studies have explored how individuals engage in collective reflection (Boud et al. 1985; Raelin, 2001). This type of dialogue with others (e.g. with colleagues) (Hilden & Tikkamäki, 2013; Tsang, 2007) is embedded in processes of interaction, opinion sharing, asking for feedback, challenging groupthink and collective experimentation and innovation. In addition to these individual and collective dimensions, there are contextual factors in reflection related to organisational structures, practices and culture (Elkjaer, 2001; Jordan, 2010), physical work environment and time pressures. Reflection must be supported by suitable organizational structures and practices; of crucial concern is how reflection is organized and embedded in everyday work. These three essential levels of analysis (individual, collective and organizational) are broadly accepted by learning theorists and in the management literature (Crossan, Lane & White,1999; Hoyrup, 2004).

At its best, reflection is a state of mind or an orientation leading to reflective practice, the capacity to reflect on action (Schön, 1983) to improve one’s work. This is an active, dynamic, action-based and ethical set of skills, located in real time and dealing with real, complex and difficult situations (Bright, 1996). Reflective practice is a complex emotional and intellectual process that calls for self-awareness, self-regulation and interaction with others. Reflecting on different approaches to work and reshaping understanding of past and current experiences can lead to improved work practices (Leitch & Day, 2000), as well as to modification of skills to suit specific contexts and situations, and ultimately to the invention of new strategies (Larrivee, 2000). Definitions of reflective practice share some characteristics of cognitive stress theory’s (Lazarus, 2001) secondary appraisal process in evaluating the availability of coping resources. ‘Coping’ refers to the constantly changing cognitive and behavioural efforts one makes to manage demands appraised as taxing or as exceeding one’s resources.

Although organizational learning theorists have noted the importance of reflection and reflective practice (Schön, 1983; Weick & Sutcliffe, 2001), discussion has for some reason been confined largely to learning and has not been fully integrated with stress research. However, a few exceptions reveal the links between reflective practice and experiences of stress. One such study showed a significant positive correlation between rumination and stress, and self-reflection was negatively associated with distress (Smaie & Farahani, 2011). In another study, among other interventions, Bono, Glomb, Shen, Kim and Koch (2013) asked health care professionals to reflect on their work by writing down three good things that had happened during their day. The aim was to help employees to shift the focus of attention to positive events, to benefit from positive events by recognizing and making sense of them and to savour events both individually and with others. The results showed that this kind of reflective intervention helped employees to reduce distress, with a statistically significant reduction in reported health complaints.

Beyond these studies, there is (to our knowledge) no earlier research linking reflective practice explicitly to positive stress experiences, and more research is needed, especially in an entrepreneurial context. Many aspects of that earlier research, such as the important role of interpretation in transactional stress theories and the conceptual similarities between reflectivity and coping, invite further exploration of links between the capacity and willingness to reflect and experiences of eustress and balance.

As we understand it, reflective practice can also be viewed as a metalevel component of psychological capital, which may further illuminate connections between positive stress experiences and reflection. According to Jensen (2012), psychological capital involves self-efficacy, hope, optimism and resilience—characteristics that may hold the key to understanding entrepreneurial stress. Recognising and building psychological capital may help to clarify how individuals respond to stressors in an entrepreneurial environment and how they develop coping strategies to deal with stress. Again, psychological capital is constructed and reinforced through processes of conscious (self-)evaluation and examination.

Research methods and data

The present study adopted a qualitative and multi-methodological approach, combining interviews, interpretations of physiological measurement data, diary-keeping and reflective dialogue between participants. The principles of reflective practice guided the research process, which was also designed to serve as a reflective process for participants, with an opportunity to participate in two peer-mentoring groups during the research process to reflect with other participants on their experiences.

As entrepreneurs have more freedom of choice than employees in their use of time and ways of working, they may also have more opportunities to engender experiences of eustress. For this reason, a study of positive stress effects among entrepreneurs can potentially provide insights into both the wellbeing of that population and the links between positive stress and reflective practice more generally. The 21 participating entrepreneurs were Finns aged 30–52 years, most of whom ran small companies with fewer than 10 employees in fields that included consulting and education, the building industry and software design. A majority were relatively new entrepreneurs (12 for less than five years).

The process of data collection and analysis proceeded in two phases. In the first phase, the 21 participants were interviewed face-to-face. These two-hour interviews were semi-structured but open, concentrating on personal experiences of entrepreneurship and positive stress. Interviews were conducted by two researchers, at the participant’s workplace or at some quiet location. To begin, interviewees were asked to trace their personal history as an entrepreneur and to describe their everyday working life. Second, they were asked to recall at least one experience of positive stress (if any) and to elaborate on their related emotions, behaviours and attitudes. Third, they were asked to identify any factors they considered relevant in achieving a state of positive stress. Given the exploratory nature of our research, the interview questions were broad and open. The aim was to encourage participants to mention anything that was meaningful to them. Questions relating specifically to reflective practice were deferred to the end of the interview and included the following:

- Do you think over and analyse your working habits and behaviour from the point of view of stress or wellbeing? If so, how do you do it?

- What have you learned about yourself and stress management during your time as an entrepreneur?

Transcribed interview data were thematically analysed; coding followed the steps defined by Braun and Clarke (2006). The analysis proceeded as follows:

- Familiarization with data. The transcribed data were first read through in their entirety by four of the project researchers. The main content of each interview was discussed within the multidisciplinary research team to build a mutual understanding of the data that would form a basis for analysis.

- Generating initial codes. All data were then systematically coded. The aim was to code all available methods of stimulating positive stress. Initial coding was data-driven and analysed without reference to any preconceived framework.

- Searching for themes among codes. Based on their similarities, codes related to stimulating positive stress were then grouped into wider themes. This bottom-up analysis generated six main themes (later defining the toolsets in the positive stress toolbox). One of these six themes related to reflection and reflective practice (later named the reflective practice toolset).

- Reviewing themes. The six themes were further analysed to identify tools that entrepreneurs considered meaningful in managing positive stress. This further analysis produced 24 subthemes (later named as the tools of the toolbox). Within these themes, quotations were thematically grouped according to their affinity. More specifically, the theme describing reflection and reflective practice was reviewed from a number of angles: descriptions of capability and willingness to reflect, the three theory-based dimensions of reflective practice (individual, social and contextual) and the data-driven categorization of this toolset into six subthemes (later named as reflective tools of the toolset).

- Defining and naming themes and production of the final report. Finally, all themes and subthemes were listed, with accompanying descriptions, and quotations were chosen to illustrate entrepreneurs’ experiences of reflective practice and stimulating positive stress.

In the second phase, nine of the interviewed entrepreneurs recorded a positive stress diary, including a three-day physiological measurement analysing heartbeat variability. The second phase was designed to deepen the research data, using those participants who volunteered to further explore and reflect on their positive stress experiences. While interview data in the first phase drew on past experiences, the second phase complemented this by addressing ongoing eustress experiences. Nine volunteers wore equipment to measure heartbeat variability (Firstbeat) for three days during everyday work, sleep and leisure time. A personal report from each volunteer included a 24/7 profile of factors that affected well-being and performance. Researchers were trained to interpret the report by the service provider, but the physiological data was not analysed as such; instead, it was used as a research and reflection method to help participants to increase their understanding of the experience of positive stress. The researchers walked participants through the results during a second face-to-face interview to explore how entrepreneurs themselves interpreted and described the eustress experiences recorded in the diary notes and physiological data. Interview data were again transcribed and analysed, using the same procedurę as in the first phase. However, in this second phase, codes and themes were constantly mirrored to the results of the first phase to identify any similarities or conflicts between the two data sets. The same six main themes were again identified in this second data set, yielding further insights into some subthemes. This phase provided real-time information about positive stress experiences and also helped participants to understand their behaviour at a physiological level. This two-phase approach provided an opportunity to explore the learning and development process of volunteering participants.

Toolset for reflective practice promoting eustress

All those interviewed recognised the phenomenon of positive stress; indeed, the enthusiasm and positive experiences linked to eustress were even seen as reasons for becoming an entrepreneur, as they led one to feel that the work was rewarding. The entrepreneurs described their eustress experiences as a state of enjoyment and productivity, making the work feel effortless. According to one entrepreneur,

It is like dancing on the water. Like getting wings ... Things are solved, although there is some pressure. Or I’d claim that they are solved because of the pressure (Female, 38 years old, consulting).

In addition to individual achievements, positive stress was often linked to social situations, where insecurity, meaningfulness of the situation and shared enthusiasm facilitated experiences of eustress. As one entrepreneur stated,

I feel it is more important that the crew is in such a state [of eustress] rather than the individual (Male, 45 years old, digital consulting).

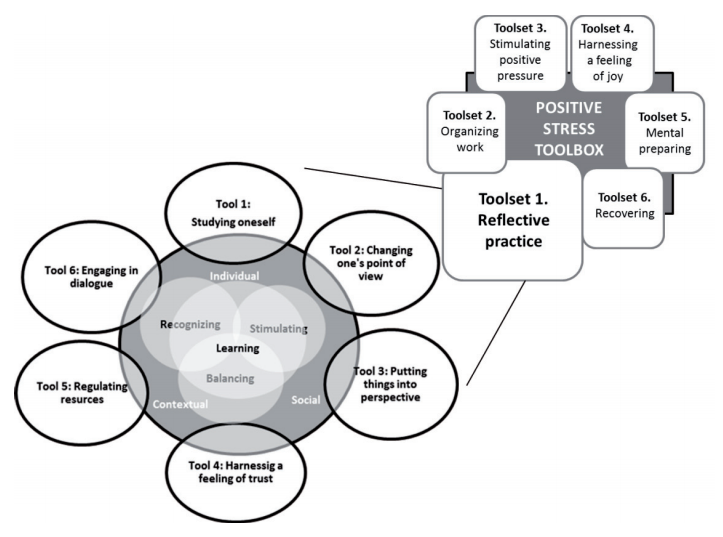

Entrepreneurs’ experiences of eustress were analysed by identifying the tools they use to recognise and stimulate positive stress and to balance positive and negative stress. Based on categorization of the collected data, six eustress toolsets were identified: reflective practice, organizing work, stimulating positive pressure, harnessing feelings of joy, preparing mentally and recovering (Figure 1). Together, these six toolsets constituted a positive stress toolbox related to job crafting (Berg, Dutton & Wrzesniewski, 2013; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001), promoting entrepreneurs’ capability to reshape the boundaries of their work practices through task, relational and cognitive crafting.

Among the six toolsets, the reflective practice toolset was identified as crucial for promotion of eustress, and this toolset was therefore selected as the focus of this paper. In the next sections, we concentrate on the content and meaning of this reflective practice toolset; the remaining five toolsets fall outside the scope of this paper.

Capability and willingness to reflect

The entrepreneurs varied in their capability and willingness to reflect. Those who were not reflection-oriented reported that they acted mainly on their intuition. However, many others regularly used reflective ways of thinking and working and believed this practice to be beneficial. In particular, entrepreneurs from the training and consulting sectors seemed to have internalised reflective practice as a way of analysing past experiences and oneself. One entrepreneur shared the following observation:

You sit on the plane and start to think what happened during the past three days. You start to list down that this went well, this went well, this is a bit unfinished, and this is where we flopped and the reasons for it … I analyse my environment, and myself, and I know my strengths and weaknesses, and actually, there are plenty of weaknesses… (Male, 52 years old, pet shop entrepreneur).

Most of the participants were interested in developing their work practices, and participation in the study encouraged them to reflect on their ways of working and thinking. Interacting with the researchers, writing down their experiences and interpreting their physiological data all supported a reflective orientation. For example, one entrepreneur first thought that eustress referred to enthusiastic, puppy-like rushing around. However, having completed all the research steps, he realised that eustress was actually most likely to occur when he remained calm and truly concentrated on his actions. For another entrepreneur, the research process was a trigger for thinking about her life situation at a broader level:

The thing that got me to think about my feelings in this study was asking, ‘Does it make any sense just to rush around and neglect your well-being all the time?’ … I’ve been thinking on a wider scale what carries me on. And I’ve been listening to others about what they tell about themselves and their recovery (Female, 49 years old, consulting).

Individual, social and contextual dimensions of reflective practice

Although both individual and social dimensions of reflective practice were discerned from the data, the emphasis was on individual reflection. Many of the entrepreneurs reported that they analyse and consciously think over their ways of thinking and doing, as illustrated by the following two excerpts:

I’m not sure whether it is self-analysis, but you need to be, all the time, a bit conscious of where you are going. Because it [stress] gets you so easily, negative stress especially (Female, 43 years old, cleaning services).

What I have learned about entrepreneurship is that it is continuously proceeding. But also stopping to think what you have achieved, what you have learned and how you utilize it (Female, 38 years old, training/consulting).

The data also contained many examples of the social dimension of reflective practice; in practice, this meant discussing and analysing with colleagues, professionals and close associates. As the following two excerpts suggest, reflective dialogue also played a role in joint innovation.

I think it is part of our way of working, all the time, embedded in it … The idea of continuous reflection is in our backbones ... I think we do it every day; we think whether we could do this better or whether a way of doing things is a practical or appropriate one (Female, 46 years old, training/consulting).

Many moments of positive enthusiasm come when we sit down together and process things … It was sort of a state of enthusiasm, you know, such that the thing got clearer, we understood it together, a sort of positive excitement. Then you automatically get up and start to make it on the flip chart together, you can see that people get excited when they do it together… (Male, 41 years old, consulting).

Contextual factors were also identified as having an impact on reflective practice. The examples from entrepreneurs’ experiences related to an inspiring work environment and the importance of occasionally changing that environment to see things from different angles. While some entrepreneurs reported that they struggled to find time for reflection, others had explicitly allocated such time—for example, reserving one day a week for self-development.

The reflective practice toolset

The reflective practice toolset consists of the following six reflective tools:

- Studying oneself

- Changing one’s point of view

- Putting things into perspective

- Harnessing a feeling of trust

- Regulating resources

- Engaging in dialogue

n practice, studying oneself (tool 1) means that entrepreneurs recognized, analysed and evaluated their ways of thinking and doing. Changing one’s point of view (2) refers to examining situations and experiences openmindedly and from different perspectives (e.g. from the client’s perspective) and, in particular, from a positive point of view. For example, seeing failure as a potential guide for learning is one way to detect the positive. Putting things into perspective (3) relates to thinking about life on a broader scale—for example, remembering that business is only one dimension of life. Harnessing a feeling of trust (4) refers both to trusting oneself as a professional and trusting the future. Building confidence in one’s own abilities also includes forgiving oneself, allowing oneself to occasionally say ‘no’ and avoiding making decisions just to please others. Regulating resources (5) means assessing where to get involved and justi fying and prioriti zing one’s own acti ons—on the one hand, you must harness enthusiasm, and on the other, you must be mindful of working too much without taking ti me to recover. Engaging in dialogue (6) with professionals, colleagues, friends or family refers to talking aloud and sharing ideas, experiences and feelings (Figure 1).

The entrepreneurs exploited these six tools in diff erent ways to externalize their thinking, experiences and feelings. For example, some made lists or visualized their ideas and/or goals, thought aloud and/or asked questi ons. During the research process, refl ecti ve practi ce produced new insights into benefi cial or harmful ways of thinking and working. Many of the entrepreneurs realized the importance of suffi cient ti me for sleep and recalled ways of recovering from stress

In summary, the data confi rmed that capacity and willingness to refl ect were considered crucial for experiences of eustress. Refl ecti ve practi ce in relati on to positi ve stress highlighted entrepreneurs’ ways of recognizing, sti mulati ng and/or balancing eustress. Refl ecti ve tools were used to interpret stress/pressure experiences, to evaluate personal ways of coping and to construct an understanding of demands and resources. This enabled entrepreneurs to learn about themselves and from their own stress experiences, both individually and in the company of others

Discussion: Eustress and reflective practice supporting balance

Among those interviewed, eustress was seen as a state of enjoyment and productivity that was worth pursuing. Our results therefore confirm the need for research that takes account of the positive aspects of stress. Entrepreneurs reported their own personal ways of striving for eustress experiences, and one subset of these tools can be grouped under the theme of reflective practice. This aligns well with traditional transactional theories of stress (Cox, 1978; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) that emphasise interpretation of stressors (e.g. primary and secondary appraisal) as a key factor in experiences of stress.

While positive stress among entrepreneurs has not previously been explicitly studied, our results offer preliminary support for application of the holistic stress model and the savouring of positive stress (Simmons & Nelson, 2007) in an entrepreneurial context. According to the JDR model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004), given sufficient job resources, job demands may boost work engagement and performance. Reflective practice can also be seen as this kind of job resource, transforming demands into booster effects.

Earlier theory relating to reflective practice also proved applicable in the context of entrepreneurs and positive stress. The division of reflective practice into individual, social and contextual dimensions (see e.g.: Crossan et al., 1999; Jordan, 2010) is helpful in understanding differences between entrepreneurs. The present results also complement earlier studies highlighting the effects of reflective practice in reducing distress (Bono, Glomb, Shen, Kim & Koch, 2013; Smaie & Farahani, 2011), and our data suggest that it may be fruitful to look for the same effect with regard to savouring positive stress. However, straightforward causal relationships cannot be drawn purely on the basis of these qualitative and interpretative data.

Enhancing eustress, entrepreneurship and reflective practice demands self-leadership, which is described as a process of influencing oneself (e.g. Neck & Manz, 1992). Self-leadership skills facilitate behavioural management, using strategies of intrinsic motivation and reward as well as constructive thought patterns. Self-leadership also relates to optimism, happiness, conscientiousness, as well as an open personality, high internal locus of control, self-monitoring and need for autonomy (D’Intino, Goldsby, Houghton & Neck, 2007). In one form of self-leadership—thought self-leadership— the emphasis is on self-talk, beliefs/assumptions and mental imaginary in performance (Neck & Manz, 1992; Neck et al., 1999), echoing the idea of a reflective practice toolset presented here. D’Intino et al. (2007) characterised self-leadership among entrepreneurs in the following way: ‘The goal of increased self-leadership for entrepreneurs is for these individuals to more effectively lead themselves by learning and applying specific behavioural and cognitive strategies to improve their lives and their entrepreneurial business ventures’.

Positive stress and reflective practice are linked to many existing concepts, and these links should be further elaborated in future research. While some of the eustress experiences described by entrepreneurs had flow-like elements, our data illustrate the same relationship between flow and eustress as that reported by Hargrove et al. (2013): that flow is not necessarily or evidently but possibly an epitome of eustress. One other concept that might usefully inform future research is the idea of psychological capital; following Jensen (2012), this may provide the key to understanding entrepreneurial stress. Other closely related concepts include job crafting (see e.g.: Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001), work engagement (see e.g.: Schaufeli et al., 2002) and selfleadership (e.g. Manz, 1983).

The main aim of this paper was to characterise the results of the first research phase of our project by highlighting the reflective practice toolset from the positive stress toolbox. A central question for future research is how these reflective tools and the other tools from the positive stress toolbox can be taught and learned as part of everyday work. The challenge is to find the most efficient ways of assimilating these reflective practices into everyday work and then to maintain these habits. Preliminary answers may be found in the project’s next phase, where a new group of volunteer entrepreneurs are testing a digital version of the positive stress toolbox as part of their daily life.

Both the strengths and the limitations of this study lie in the qualitative and reflective research approach. While this provided solid benefits for present purposes, statistical generalization to all entrepreneurs cannot be drawn on the basis of these data. Although some valuable insights were gained, quantitative methods would provide another perspective and add value to these results. Additionally, all the entrepreneurs who participated in this study were Finnish, and most of them represented quite small firms; international, cross-cultural research could be expected to enrich this picture in the future.

Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to contribute to entrepreneurship research by exploring entrepreneurs’ descriptions of positive stress and reflective practice in their everyday experience. Following an overview of approaches to stress at work and the link to reflective practice, our approach drew on a positive psychology perspective, exploring individually and socially constructed interpretations and tools for finding and sustaining resources and balance. After setting out our research process and methods, we went on to describe entrepreneurs’ experiences of eustress and reflective practice at work.

The present results suggest that positive stress and reflective practice are intertwined in the experiences of entrepreneurs. With regard to eustress, the results confirm that reflective practice is a useful tool, both to stimulate good practices and to survive and learn from drawbacks and experiences of failure or success. Reflective practice offers more grounded self-knowledge and a means of identifying a personally acceptable level of eustress, as well as how best to recover, how to regulate workload and other job pressures and one’s own activity in terms of resources at hand—in short, how to find a balance in life.

Based on the experiences of the entrepreneurs, we also described their tools for reflection. This reflective practice toolset comprised the following six reflective tools: studying oneself, changing one’s point of view, putting things into perspective, harnessing a feeling of trust, regulating resources and engaging in dialogue. These tools were found to be useful for enhancing recognition and stimulation of eustress; for striking a balance between distress, eustress and recovery; and for developing ways of thinking and doing through learning.

The literature review confirmed a lack of research on positive stress experiences among entrepreneurs and in particular on the relationship between positive stress and reflection. Through qualitative analysis, the present study represents an exploratory step towards closing this gap by confirming that reflective practice plays an important role in entrepreneurs’ experiences of eustress. Specifically, entrepreneurs reported how they used tools of reflective practice to interpret stress experiences, evaluate own ways of coping and construct an understanding of demands and resources.

The wellbeing of entrepreneurs is to a great extent in their own hands. The challenge is to be effective and innovative while also taking care to make time for recovery by balancing different demands and possibilities. The present research illustrates how tools for reflective practice and for savouring eustress can help entrepreneurs to balance wellbeing and effectiveness at work, offering a point of departure for further and more systematic research.

References

- Amabile, T., Barsade, S.G., Mueller, J.S., & Staw, B.M. (2005). Affect and Creativity at Work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50, 367–403.

- Argyris, C. & D.A. Schön. (1996). Organizational learning 2: Theory, method, practice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley

- Anderson, N. De Dreu, C.K, & Nijstad, B.A. (2004). The routinization of innovation research: a constructively critical review of the state-of-thescience. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 147-173.

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands–resources theory. Wellbeing: A complete reference guide, 3, 37-64.

- Bakker, A.B. (2015). Towards a multilevel approach of employee well-being. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(6), 839- 843.

- Berg, J.M., Dutton, J.E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. In B.J.Dik, Z.S.Byrne & M.F.Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81-104). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Bono, J.E., Glomb, T.M., Shen, W. Kim, E., & Koch, A.J. (2013). Building positive resources: effects of positive events and positive reflection on work stress and health. Academy of Management Journal, 56(6), 1601-1627.

- Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). What is reflection is learning? In D. Boud, R. Keogh and D. Walker (Eds.) Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning (pp. 7-17). London: Kogan Page.

- Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (2002) Promoting reflection in learning. A model. In R. Edwards, A. Hanson & P. Raggat (Eds.) Boudaries of Adult Learning (pp. 32-56). New York: Routledge.

- Boud, D., Cressey, P., & Docherty, P. (2006). Setting the scene for productive reflection. In D. Boud, P. Cressey & D. Docherty (Eds.), Productive Reflection at Work: Learning for changing work. (pp. 1-25). London: Routledge.

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Bright, B. (1996). Reflecting on reflective practice. Studies in the Education of Adults, 28(2), 162-184.

- Cardon, M. S., & Patel, P. C. (2015). Is Stress Worth it? Stress-Related Health and Wealth Trade-Offs for Entrepreneurs. Applied Psychology, 64(2), 379-420.

- Cheetham, G. & Chivers’s, G. (1998). The reflective (and competent) practitioner: a model of professional competence which seeks to harmonise the reflective practitioner and competence-based approaches. Journal of European Industrial Training, 22(7), 267 – 276.

- Cox, T. (1978). Stress. London: MacMillan.

- Crossan M., Lane, H., & White, R. (1999). An organisational learning framework: From intuition to institution. Academy of Management, 24(12), 522–537.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Logic: The Theory of Inquiry. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

- Elkjaer, B. (2001). The learning organization: and undelivered promise. Management Learning, 32(4), 437-452.

- Frese, M. (2009). Towards a Psychology of Entrepreneurship — An Action Theory Perspective. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 5(6), 437-496.

- George, J.M. & Zhou, J. (2002). Understanding when bad moods foster creativity and good one’s don’t: The role of context and clarity of feelings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(4), 687-697.

- Guest, D.E. (2002). Perspectives on the study of Work-Life balance. Social Science Information, 41(2), 255-279.

- Hargrove, M.B., Nelson, D. L., & Cooper, C. (2013). Generating eustress by challenging employees: Helping people to savor their work. Organizational Dynamics, 42(1), 61-69.

- Harris, J.A, Saltstone, R., & Fraboni, M. (1999). An evaluation on the job stress questionnaire with sample of entrepreneurs. Journal of Business and Psychology, 13(3), 447-455.

- Hilden, S. & Tikkamäki, K. (2013). Reflective Practice as a Fuel for Organizational Learning. Administrative Sciences, 3(3), 76-95.

- Hoyrup, S. (2004). Reflection as a core process in organizational learning. Journal of Workplace Learning, 16(8), 442-454.

- D’Intino, R.S., Goldsby M.G, Houghton J.D., & Neck C.P. (2007). SelfLeadership: A process for entrepreunial success. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 13(4), 105-120.

- Jensen, S.M. (2012). Psychological Capital: Key to understanding entrepreneurial stress?, Economics & Business Journal: Inquiries & Perspectives, 4(1), 44-55.

- Jordan, S. (2010). Learning to be surprised: how to foster reflective practice in a high-reliability context, Management Learning, 41(4), 391-413.

- Karasek, R.A. & Theorell T. (1990). Healthy work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. The American journal of Public Health, 80(5), 1013-1014.

- Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as a Source of Learning and Development, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-HallPublisher.

- Kuratko, D. F. (2007) .Entrepreneurial Leadership in the 21st Century. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 13(4), 1-11.

- Langan-Fox, J. & Roth, S. (1995). Achievement motivation and female entrepreneurs. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 68(3), 209-218.

- Lazarus, R.S. (1966). Psychological Stress and the Coping Process. New York: McGraw-Hill

- Lazarus, R.S. (2001). Relational meaning and discrete emotions. In K.R.Scherer, A. Schorr and T. Johnstone (Eds.), Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research. Series in affective science., (pp. 37-67). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Lazarus, R. S. & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress.Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer.

- Leitch, R. & Day, C. (2000). Action research and reflective practice: towards a holistic view. Educational Action Research, 8(1), 179–193.

- Larrivee, B. (2000). Transforming teaching practice: becoming the critically reflective teacher. Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 1(3), 293–307.

- Le Fevre, M., Matheny, J., & Kolt, G.S. (2003). Eustress, Distress, and Interpretation in Occupational Stress. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(7), 726-744.

- Manz, C.C. (1983). The art of self-leadership: Strategies for personal effectiveness in your life and work, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Mahoney, M. & Arnkoff, D. (1978). Cognitive-self control therapies. In S. Garfield and A. Bergen (Eds.) Handbook of psychotherapy and’behavior change (pp. 689-722). New York: Wiley.

- Mezirow, J. (1981). A critical theory of adult learning and education, Adult Education, 32(1), 3-24.

- Neck, C.P. & Manz, C.C. (1992). Thought self-leadership: The influence of self-talk and mental imagery on performance, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(7), 681-699

- Neck, C.P., Neck, H.M., Manz, C.C., & Godwin, J. (1999). “I think I can”: A selfleadership perspective toward enhancing entrepreneur thought patterns, self-efficacy, and performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 14(6), 477-501.

- Palmer, M. (1971). The application of psychological testing to entrepreneurial potential. California Management Review, 13(2), 38-48.

- Raelin, J.A. (2001). Public reflection as the basis of learning. Management Learning, 32(1), 11-30.

- Rahim, A. (1996). Stress, Strain, and Their Moderators: An Empirical Comparison of Entrepreneurs and Managers, Journal of Small Business Management, 34(1), 46-58.

- Samaie, Gh. & Farahani, H.A. (2011). Self-compassion as a moderator of the relationship between rumination, self-reflection and stress, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 978 – 982.

- Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71-92.

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293-315.

- Schön, D.A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books.

- Seligman, M.E. & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14.

- Selye, H. (1974), Stress Without Distress. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company.

- Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Occupational Health Psychology, 8(1), 27-41.

- Simmons, B.L. & Nelson, D.L. (2007). Eustress at Work: Extending the Holistic Stress Model. In D.L. Nelson and C.Cooper (Eds.). Positive Organizational Behaviour (pp. 40-53). London: Sage.

- Tsang, N.M. (2007). Reflection as dialogue. British Journal of Social Work, 37(4), 681–694.

- Wrzesniewski, A. & Dutton, J.E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179-201.

- Zimmerman, B.J. (1995). Self-Regulation involves more than metacognition: a social cognitive perspective. Educational Psychologist, 30(4), 217-221.

Biographical notes

Kati Tikkamäki (D.Ed.) has worked as a researcher and teacher at the University of Tampere, Finland for about 15 years. She is currently a senior researcher in work-life development research programmes related to topics that include eustress, reflective work practice and dialogic leadership. She is also a freelance trainer and trained supervisor.

Päivi Heikkilä (M.Sc.) works as a researcher in the Human-Driven Design and System Dynamics team at VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland. She has worked as a user experience expert, researcher and project manager on projects relating to user needs and the potential of novel digital services. She is currently project manager for the Eustress project.

Mari Ainasoja (M.Sc. (Econ. and Bus. Adm.)) works as a researcher and project coordinator at the University of Tampere, Finland. She specializes in collaborative research with companies for business development. Her research interests include a wide range of topics, from feelings and stress in business to service development and digital marketing.