Aleksandra Spik, PhD, University of Warsaw, Faculty of Management, Department of Organization Theory and Methods, ul. Szturmowa 1/3, 02-678 Warszawa. E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Abstract

The aim of this article is to investigate the relationship between organizational commitment profiles and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and life satisfaction. To complete these goals three studies were conducted. The research involved the cultural adaptation of the internationally accepted standard Organizational Commitment Questionnaire and the development of the Organizational Citizenship Behavior Questionnaire. The first study (N=40) focused on the validation of translation and cultural adaptation of the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (Meyer & Allen, 1991, 1997). The second study (N=222) was aimed at confirming the factor structure and psychometric properties of the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire – Polish version. In the third study (N=42) the Organizational Citizenship Behavior Questionnaire was obtained. In the next study (N=503) the main research hypotheses were examined. Five clusters were identified using k-means cluster analysis. These were labeled: Non-committed, Neutrals, Enthusiasts, Trapped and Devoted. Analysis of variance results indicated that Enthusiasts and Devoted demonstrated the highest levels of OCB and high levels of life satisfaction. The Non-committed profile showed the lowest level of OCB combined with low levels of life satisfaction.

Keywords: organizational citizenship behavior, affective commitment, normative commitment, continuance commitment.

Introduction

Scholars and practitioners of management often investigate on the source of competitive advantage characteristic for successful firms. The value of innovations as a competitive advantage is increasing (Rodriguez, Ricort & Sanchez, 2002). In light of this approach, employees are considered a valuable asset since they are often the ones to invent or implement innovations. Deciding how to enhance innovative attitudes of employees is an issue organizations operating in a highly competitive market have to address. Organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior could be an answer to this problem

Lee and Kim (2010) argue that, contrarily to a traditional model of HRM, commitment-based HRM enhances the initiative and creativity of employees. Commitment–based human resource management is a set of practices leading to increased commitment of employees. Therefore, an organization in a highly competitive environment can achieve higher performance through the genuine commitment of employees. Commitment oriented HR practices were found to have a positive effect on innovation activities (Shipton, West, Dawson, Birdi & Patterson, 2006; Chen & Huang, 2009; Lee & Kim, 2010). Research results emphasize that commitment-based HRM boosts company performance through its effect on innovation activities (Ceylan, 2013; Jiménez Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2008). A committed workforce, which is willing to go the extra mile for the organization, can be a competitive advantage not easily copied by competitors (Pffeffer, 1994).

Understanding what the types of commitment are and how they influence the attitudes and behaviors in the workplace has been an interest of many scholars for over fifty years (e.g. Becker, 1960; Begley & Czajka, 1993; Brown, 1996; Gellatly, Meyer & Luchak, 2006; Devece, Palacios-Marques & Alguacil, 2015). Research results show that organizational commitment is related to employee turnover, job satisfaction, absenteeism and organizational citizenship behavior (Jamal, 2011). However, Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky (2002) indicated that there was a need for more systematic research in different contexts and geographical locations to explain the existing discrepancies in research results. A new approach to organizational commitment has been advanced to achieve this goal (e.g., Wasti, 2006, Somers, 2009). In this approach, organizational commitment is assessed as a profile of three independent attitudes not, as previously, as separate variables. The research presented in the article is in line with this approach.

Many researchers agree that OCB are indispensable for every organization to survive (Smith, Near & Organ, 1983; Organ, Podsakoff & Mac Kenzie, 2006). Katz and Kahn (1979) asserted that innovative and spontaneous behavior was crucial to organizational survival. The term describing a wide range of cooperative, innovative and spontaneous behaviors is organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) (Organ et al., 2006). OCB is explained as a discretionary contribution that goes beyond the strict description of the job and does not claim any recompense from the reward system (Organ et al., 2006, p. 34). There is a link between OCB and innovativeness of organizations. OCB supports an innovative organizational climate (Turnipseed & Turnipseed, 2013). Research suggests there is a positive relationship between OCB and employees offering new ideas (Turnipseed & Wilson, 2009).

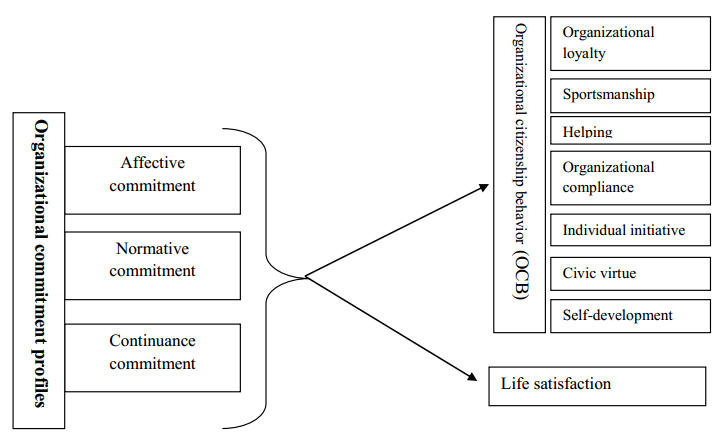

The aim of this article is to examine what are the commitment profiles (in terms of the three types of this attitude) among employees who improve their education on extramural business studies. The conceptual model of research is presented in Figure 1. The research focuses on examining the relationship between commitment profiles, OCB, and life satisfaction. The research was aimed at a comprehensive examination of OCB and commitment profiles, since no previous research had assessed the relations between organizational commitment and all 7 types of OCB. To complete this goal, the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (Meyer & Allen, 1991, 1997) was culturally adapted and the scale of Organizational Citizenship Behavior was developed. Both concepts have received to date very little interest in Polish scientific circles.

Theoretical Framework – Literature Review

Organizational Commitment

The organizational scholars’ interest in organizational commitment dates back to the 1960s. Howard Becker, the pioneer of commitment conceptualizations, posited that “commitments came into being when a person by making a side bet, links extraneous interest with consistent line of activity” (1960, p. 37).

The influence of Becker’s conceptualization is noticeable in many recent commitment theories. It can be detected especially in models that perceive commitment as a multidimensional construct (Allen & Meyer, 1991; O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986; Angle & Perry, 1981; Jaros, Jermier, Koehler & Sincich, 1993; Cohen, 2007). The influence of side bet theory is evident in Meyer and Allen’s continuance type of commitment.

A different approach to organizational commitment was advanced by Lyman Porter (1974). The focus of commitment shifted from side-bets to the psychological attachment one has to an organization (Cohen, 2007, p. 338). Mowday and colleagues designed a tool to measure commitment called the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire. The instrument was treated as one-dimensional. Porter’s theory contributed to later conceptualizations. Porter’s commitment constitutes the affective type of commitment in Meyer and Allen’s Three-Component Model (1991, 1997).

Other researchers claimed that this approach was oversimplifying the complex nature of commitment (Meyer & Allen, 1984; O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986). Those critiques led to several multidimensional approaches (Angle & Perry, 1981; O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986; Penley & Gould, 1988; Meyer & Allen, 1991; Mayer & Shoorman, 1992; Jaros et al., 1993; Meyer & Herscovitch, 2002). In Table 1 a set of definitions of multidimensional approaches to organizational commitment is provided.

Research presented in the article is based on the Three-Component Model of commitment (TCM), (Allen & Meyer, 1991, 1997). This model prevails in research on commitment in a workplace (e.g., Chinen & Enomoto, 2004; Cohen, 2007, Gellatly et al., 2006; Somers, 2009). Natalie Allen and John Meyer (1991) contended that all multidimensional perspectives could by integrated in three major categories of commitment (Meyer & Allen, 1997, p. 11):

- Affective commitment (AC) – emotional attachment and identification with the employee organization. It reflects the extent to which an employee wants to be a member of the organization.

- Continuance commitment (CC) - refers to the awareness of the costs associated with leaving the organization. Employees who are linked to an organization on the basis of continuance commitment remain because they need to do so.

- Normative commitment (NC) – reflects a feeling of obligation to continue employment. Employees with a high level of normative commitment feel that they ought to remain in the organization.

| Authors | Types of commitment | Definitions |

|---|---|---|

| Angle & Perry (1981, p. 4) | Commitment in values Commitment to stay in organization | “Involvement in supporting organizational goals”. “Involvement in maintaining the membership in organization.” |

| O’Reilly & Chatman (1986, p. 493) | Compliance Identification Internalization | “Attitudes and behaviors are adopted to gain specific rewards.” “Individual accepts influence to maintain the membership in organization.” “The values of individual and organization are the same.” |

| Penley & Gould (1988) | Moral Calculative Alienative | “Acceptance and identification with organizational goals.” (p. 44) “An employee exchanges his or her contributions for the inducements provided by organization.” (p. 44) “Negative affective attachment to organization. Consequence of lack of control and absence of alternatives.“ (p. 47) |

| Meyer & Allen (1991, p. 7) | Affective Normative Continuance | “Emotional attachment and identification with organization.” “Feeling of obligation to continue employment.” “Awareness of the costs associated with leaving the organization.“ |

| Mayer & Shoorman (1992, pp. 673-674) | Connected with values Continuance | “Acceptance of organizational goals and willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of organization.” “Desire to maintain the membership of organization.” |

| Jaros et al. (1993, pp. 953-955) | Affective Continuance Moral | Form of psychological attachment to organization through feelings such as loyalty, warmth, belongingness, affection. Form of psychological attachment to organization that reflects the degree to which an individual experiences the sense of being locked in place because of high cost of leaving. The degree to which an individual is psychologically attached to organization through internalization of its goals, values and missions.” |

| Meyer & Herscovitch (2001, p. 308) | Affective Continuance Normative | “The core essence of every commitment is a force that binds individual to a course of action of relevance to one or more targets (…) the mind-set accompanying commitment can take various forms.” |

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB)

Theoretical construct of organizational citizenship behavior was advanced by two researchers: Dennis Organ (Bateman & Organ, 1983) and Ann Smith (Smith, Organ & Near, 1983). They described OCB as discretionary activities in the workplace that were necessary for organizational functioning but they were neither strictly required by the job descriptions nor rewarded by formal incentives. This kind of behavior is also called “good soldier syndrome” (Organ et al., 2006). The organizational profits from OCB are indisputable. “OCB lubricate the social machinery of the organization. They provide the flexibility to work through many unforeseen contingencies” (Smith et al., 1983, p. 654).

In meta-analyses of literature on OCB, Podsakoff and his colleagues identified about thirty different types of such behavior (Podsakoff, Mac Kenzie, Paine & Bachrach, 2000). A variety of taxonomes were proposed to classify these activities (see e.g.: Van Dyne & Le Pine, 1998; Borman & Motowidlo, 1997; Podsakoff et al., 2000). Podsakoff and colleagues advanced a taxonomy that integrated propositions of other scholars (Organ et al., 2006). It consists of seven types of OCB (Organ et al., 2006, pp. 297-311):

- Helping. A type of OCB similar to altruism proposed by Ann Smith (1983). Such behavior involves voluntarily helping coworkers in work-related problems. In this category are also acts that improve morale, encourage cooperation, build and preserve good relationships in the workplace.

- Sportsmanship. This category involves bearing inconveniences and impositions of work without complaining, being willing to sacrifice personal interest for the good of the work group.

- Organizational loyalty. This category encompasses promoting the company image, remaining committed even under adverse conditions, defending an organization against external threats.

- Organizational compliance. This type comprises all behaviors that refer to following organizational rules and procedures, complying with organizational values, respect for authority, conscientiousness, meeting deadlines.

- Individual initiative. It is actively trying to find ways to improve individual, group or organizational functioning, including: voluntarily suggesting organizational improvements, acts of creativity and innovation designed to improve one’s tasks.

- Civic virtue. It is responsible, constructive involvement in the political process of the organization. It includes: attending non-obligatory meetings, sharing informed opinions with others, being willing to deliver bad news if it is necessary for the good of the organization, keeping abreast of different issues concerning the organization.

- Self-development. It stands for self-training, seeking out and taking advantage of advanced training courses. Self-development encompasses also keeping abreast of the latest development in one’s field, learning new kinds of skills so as to expand the range of one’s contribution to an organization.

The interest in OCB has grown substantially in recent years. More than 2100 articles on OCB can be found in literature (Podsakoff, Podsakoff, Mac Kenzie, Maynes & Spoelma, 2013, p. 87). The majority of them were published in the last decade (Podsakoff et al., 2013). OCB is also seen as an important factor in boosting organizational innovativeness. For example, research shows that employees with a high OCB have a more positive attitude to new technologies and are willing to implement new technologies in their work (Ozsahin & Sudak, 2015). OCB is consistent with the suggestion and implementation phases of innovation described by Axtell, Holman, Unsworth, Wall & Waterson. (2000). Innovation in this approach is understood as a process of adopting and generating new ideas (Axtell et al., 2000; Turnispeed & Turnispeed, 2013, p. 210).

Relationship between organizational commitment profiles and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

According to Meyer and Allen (1997; Meyer et al, 2002), the main reasons for distinguishing among the three forms of commitment is the difference in their behavioral outcomes. Meyer and Allen (1997) argued that affective commitment and normative commitment would relate positively to OCB. Continuance commitment, on the contrary, would be unrelated or negatively related. Therefore, employees who remain in an organization mainly to avoid costs associated with leaving should not be prone to engage in going above and beyond the call of duty (i.e. OCB).

John Meyer and Lynne Herscovitch (2001) offered a model of commitment profiles and their behavioral consequences. Three types of commitment (affective, normative and continuance) are associated with focal and discretionary target-related behavior. Employees endorse varying levels of each commitment concurrently which creates a distinct “profile” of commitment for each employee. Different profiles have different behavioral outcomes. Assuming that every employee can be characterized by being either high or low of the three forms of commitment, Meyer and Herscovitch (2001) proposed 8 commitment profiles. These propositions are presented in Table 2.

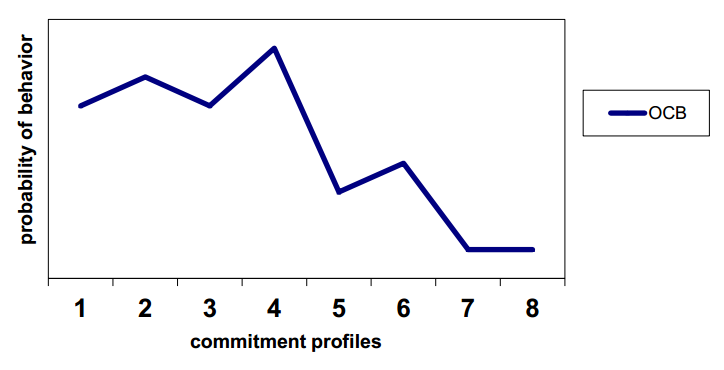

Focal behavior is explicitly specified in an agreement between an employee and the organization (Meyer, Herscovitch, 2001, p. 318). Discretionary target-related behavior is positive work behavior that is voluntary. It can be identified with organizational citizenship behavior (Wasti, 2005, p. 293; Gellatly et al., 2006). Meyer and Herscovitch (2001) assumed that frequency of discretion behaviors displayed by employees depended on the intensity of their commitment profile. Their theoretical model combines eight commitment profiles with intensity in terms of discretionary behavior (OCB). Pertaining to previous research (Meyer et al., 2002; Morisson, 1994), Meyer and Herscovitch (2001) presumed that organizational citizenship behavior had the highest correlation with affective commitment, thus, the likelihood of OCB should be greatest in the case of “pure” affective commitment (i.e. where the other forms are weak), followed by the cases in which affective commitment was accompanied by high levels of normative or continuance commitment. Regarding profiles with low levels of affective commitment, Meyer and Herscovitch (2001) expected that a “pure” normative commitment profile would be stronger associated with OCB than a profile characterized by high levels of normative and continuance commitment or “pure” continuance commitment. Continuance commitment seemed to attenuate the impact of affective and normative commitment on positive work-related behavior (OCB), (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001; Wasti, 2005). The pattern of expected relations between commitment profiles and discretionary behavior is presented in a Figure 2.

Source: Meyer & Herscovitch (2001, p. 314).

| Type of commitment | Profile 1 | Profile 2 | Profile 3 | Profile 4 | Profile 5 | Profile 6 | Profile 7 | Profile 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective | High | High | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Normative | High | High | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low |

| Continuance | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low |

| Source: Meyer & Herscovitch (2001, p. 314). | ||||||||

Research Problem and Hypotheses

The model advanced by Meyer and Herscowitch (2001) has been partially tested in several studies (Wasti, 2005; Sinclair, Tucker, Cullen & Wright, 2005; Gellatly at al., 2006; Somers, 2009; Meyer, Stanley & Parafyonova, 2012). Different results were obtained regarding the number of existing profiles. Arzu Wasti (2005) empirically supported five profiles (profiles: 1, 2, 4, 7, 8 presented in Table 2) offered by Meyer and Herscovitch (2001). He also distinguished a new profile labeled Neutrals, where all three types of commitment achieved average levels. Sinclair with colleagues (2005) modified the theoretical model of Meyer and Herscovitch (2001). The new model pertained only to affective and continuance commitment, identifying, however, three possible levels of each commitment (high, moderate, low). Five profile groups were identified (Sinclair et al., 2005).

Gellately with colleagues (2006) empirically supported all eight profiles proposed by Meyer and Herscovitch (2001). However, other researchers claimed that Gellatly et al.’s findings were not reliable due to inappropriate research method (median split) (Meyer et al., 2012).

To summarize, arguably the propositions of Meyer and Herscovitch have not received sufficient empirical support. First of all, there is a lack of consistency among obtained results. Moreover, the body of research is limited only to the U.S and Canada. Therefore, I tested the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1

Multiple (five to eight) commitment profiles with distinct patterns of AC, NC and CC exist within the employee sample.

Meyer and Allen assumed that different types of commitment had different behavioral outcomes (1991, 1997).

Research premises also supported that view. Findings showed that, affective commitment (AC) was highly positively correlated with OCB, while normative commitment (NC) showed a weaker association with OCB. Continuance commitment proved to be uncorrelated or negatively correlated with OCB (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001). However, when the combined effects of commitment components are considered, the pattern of associations gets more complex. Meyer and Herscovitch (2001) suggested that employees with a pure affective profile (strong AC combined with weak NC and CC) would display the most intensive OCB due to the strongest positive impact of AC on desirable behaviors. Research showed mixed results. According to Gellatly et al. (2006), the level of citizenship behavior for those of pure affective profile did not differ significantly from those of pure normative profile. In Wasti’s research (2005) OCB was the highest in the group of high affective and normative commitment.

These findings did not support the assumption that strong NC might mitigate the positive impact of affective commitment on citizenship behavior. In line with this argument, the following hypothesis was tested:

Hypothesis 2

Profile groups with strong affective commitment in combination with strong normative commitment and low continuance commitment have the highest level of OCB among all the profile groups.

Meyer and Herscovitch (2001) assumed that the components of commitment would interact to influence behavioral outcomes. Continuance commitment should correlate negatively with citizenship behavior. This relation would be attenuated when AC or NC (or both) are high (Meyer, Herscovitch, 2001). Research evidence has not supported to date the implied three-way interaction (Gellatly et al., 2006). However, several studies have reported two–way interactions that were consistent with Meyer and Herscovitch’s (2001) suggestion (Chen & Francesco, 2003). These findings served as a basis for development of the study hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3

Profile group with strong continuance commitment alone scores the lowest on OCB scale.

As noted previously, affective commitment is related with many positive organizational behaviors such as low absenteeism, high OCB, high quality of job performance. These outcomes of commitment are desirable for organizations. One of the objectives of the present study was to investigate the positive outcomes of commitment from the perspective of employee. Therefore, it was examined whether affective commitment was associated with employee well-being (life satisfaction). Affective commitment is defined as a state of being emotionally attached to an organization and feeling like a member of family there. It can be assumed that positive feelings toward an organization increase the overall life satisfaction of an employee. The relation between affective commitment and life satisfaction has gained to date very little interest in scientific circles (Meyer et al., 2012). Most researchers of commitment focus on work-related attitudes and behaviors. There are, however, findings showing a negative correlation between affective commitment and different measures of stress (e.g. Begley & Czajka, 1993, Ostroff, 1992). According to Meyer et al.’s findings (2012), employees that scored the highest on the positive affect scale belonged to the group of high normative and affective commitment and to the fully committed group (high AC, NC and CC). Based on this evidence, the following hypothesis regarding life satisfaction was developed:

Hypothesis 4

The highest level of life satisfaction is associated with strong affective commitment in combination with strong normative commitment

Research Methods

Measures

Organizational commitment

Organizational commitment was assessed with the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire - Polish version (OCQ-P, Spik, 2014). Scores ranged from 1 to 5 on the Likert scale. Higher scores indicate higher commitment. Reliability was obtained by Cronbach alpha of 0.715 (continuance scale), 0.848 (affective scale), 0.818 (normative scale). Prior to the main study, additional studies were conducted to adapt and validate OCQ-P. It consisted of subsequent phases.

Cultural adaptation of Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (Meyer, Allen, 1991, 1997)

Study 1 (N=40). First, all the statements taken from two Meyer and Allen’s questionnaires (18 items and 24 items) were translated into Polish. Subsequently, two independent assessors (experts in related fields, researchers with a doctoral degree from University of Warsaw) were invited to verify the items correctness and readability. In the third stage, six statements per each scale were excerpted from the items approved by assessors. It was modeled on the original pattern of Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (Meyer, Allen, 1991). In the fourth phase, the validity of cultural adaptation was examined. To this end, the results of measuring organizational commitment with both versions (original and Polish) were compared. The original version of the OCQ was assumed to be psychometrically correct (Meyer, Allen & Smith, 1993; Jaros, 1997; Hacket, Bycio & Hausdorf, 1994). To accomplish this “psychometrical strategy” of test cultural adaptation (Hornowska, 2001, p. 30) the questionnaires were completed by 40 participants. The participants were 40 employees of a large international telecommunications company operating in Warsaw, comprising 17 women and 23 men, ranging in age from 23 to 52, and with an average tenure of 3.5 years. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two equally large groups. The first group (group 1) completed the original measure of Meyer and Allen (1991) while the other (group 2) completed the Polish version. The paper-and-pencil questionnaires were distributed in the workplace. In addition, the participation was voluntary and anonymous. The participants were informed that their responses would be confidential. They were asked to fill in the questionnaire, insert it into the enclosed envelope and leave it on their desk. The envelopes were collected at the end of the day. Levene’s test was conducted to assess the equality of variance in both groups. Comparing the means with usage of T-student analysis confirmed that both measures provide similar results. Table 3 presents means and standard deviations obtained in the study.

| Type of commitment | Measure | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affective | O* P** |

17.76 16.36 |

3.621 4.050 |

| Normative | O P |

16.56 15.00 |

3.949 3.117 |

| Continuance | O P |

18.00 16.40 |

3.731 3.757 |

| Note: O*- OCQ- original version, P**- Polish version of OCQ. | |||

Examining the factor structure of OCQ-P, study 2 (N=222).

The participants in study 2 were employees of ten different organizations of different fields (e.g., banking, education, insurance, pharmacy, military). 62% were female. 38% ranged in age from 20 to 30 years, 20% ranged in age from 48 to 62 years. Data was analyzed using SPSS Version 17.0. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure in this study was 0.852. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001). Both analyses showed that the sample was sufficient to proceed to factor analysis. A Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) with Varimax rotation was conducted to determine the dimensionality of the OCQ-P. A three factor solution was obtained (eigenvalues greater than 1) with variance explained of 50.27%. The item was included in the suitable scale if the meaning of the item was theoretically consistent with the definition of the type of commitment represented by the factor, and if the PAF loading of the item was greater than 0.500. To reflect the original structure of the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire the number of items in each scale was limited to 6. Thus, in scales where more than 6 items achieved factor loadings over 0.500 only 6 items with the greatest loadings were selected to form a scale. The summary of results of PAF is presented in Table 4.

| ITEMS | Factor loadings | Changes implemented due to results of the PAF |

|---|---|---|

|

0.533 | Item was dropped from the scale due to low factor loading. |

|

||

|

0.694 | |

|

||

|

0.684 | |

|

0.581 | |

| Normative commitment scale – Factor 2 | ||

|

0.504 (Factor 1) | Dropped from the scale due to low factor loading. |

|

0.669 | |

|

0.613 | |

|

This item does not create a consistent factor with other items. Replaced with an item: “One of the main reasons that I still work for my organization is a loyalty that gives me a feeling of moral obligation to remain in the organization.” | |

|

0.766 | |

|

0.667 (Factor 1) | Item in OCQ (Allen, Meyer, 1991) belonged to normative scale. In OCQ-P item was included to affective scale. |

| Continuance commitment scale Factor 3 | ||

|

0.784 | |

|

Item does not create a theoretically consistent factor with other items. Replaced with item: “Staying in my organization is a matter of necessity. | |

|

0.521 | |

|

0.693 (Factor 2) | Item dropped from the scale. Replaced with: “Security and stability of employment are the main reasons why I remain in the organization.” |

|

0.587 | |

|

0.852 | |

Reliabilities for the scales by Alpha Cronbach estimates were: 0.72 for normative commitment, 0.70 for continuance commitment and 0.82 for affective commitment.

Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Organizational Citizenship behavior was assessed with Organizational Citizenship Behavior Questionnaire (OCBQ, Spik, 2014). OCBQ consisted of 31 items. Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient was 0.91. Scores ranged from 1 to 5 on the Likert scale. The development of the OCBQ included 4 stages.

In the first phase, 67 items from different OCB measures were translated into Polish (Williams & Anderson, 1991, Moorman & Blakely, 1995, Organ at al., 2006). Items were scored using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items pertained to seven types of OCB (Organ et al., 2006, pp. 297-311). Regarding the face validity, two independent experts in related fields were asked to provide feedback. In this stage, 4 items were dropped from the initial questionnaire. In the subsequent phase, the procedure suggested by Ann Smith was followed (Smith et al., 1983). The procedure involved asking managers to assess which items from the initial version of the questionnaire fulfilled the following criterion:

“Supervisors would like their subordinates to perform this behavior more often because it serves the good of the organization. However, these activities are neither strictly required by the job descriptions nor rewarded by formal incentives.”

The paper-and-pencil survey was administered during MBA-executive classes at University of Warsaw (study 3, N= 42). All the students were experienced executives with extensive work experience. Participation was voluntary, 42 employees participated. Any problems faced by the participants when answering the question were addressed to the researcher directly. Participants were asked to report any doubts or comments they found relevant to the issue.

9 items that participants found unclear in meaning or inadequate to Polish workplace specifics were dropped from the list of OCB, 54 items were left in the Organizational Citizenship Behavior Questionnaire (OCBQ). Subsequently, the reliability estimation of the 7 scales of OCBQ was conducted (study 4, N= 503). Findings suggested that to yield adequate reliability estimates (Cronbach alpha) several items had to be excluded from the scales. 31 items were selected from the initial 54 items. The reliability estimates of the obtained scales are listed in Table 5. Additionally, Principal Axis Factor analysis was conducted to determine the dimensionality of OCBQ. Analysis has shown that the items do not create any common factors that can be statistically and conceptually accepted. Thus, in the presented research the OCBQ scores were interpreted as a one dimension.

Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured with Life satisfaction Scale (Juczyński, 2001). Scores ranged from 1 to 5 on the Likert scale. Cronbach's alpha was 0.86.

| Scale of OCB | Initial number of items | Final number of items | Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient of the scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Helping | 8 | 7 | 0.75 |

| Civic virtue | 9 | - | 0.436 – scale excluded from further analy |

| Organizational Loyalty | 7 | 4 | 0.87 |

| Self-development | 5 | 3 | 0.67 |

| Compliance | 10 | 8 | 0.80 |

| Initiative | 8 | 5 | 0.74 |

| Sportsmanship | 8 | 4 | 0.71 |

| OCB – all items | 54 | 31 | 0.91 |

Social Desirability

Social Desirability was assessed with 5 items from the Eysenck’s Desirability Scale selected from Eysenck's Personality Questionnaire–revised (EPQ-R). Polish adaptation and normalization made by Jaworska (2008). Social desirability bias is a problem concerning research using self –report methods. Participants who are particularly sensitive on social desirability have a tendency to over-report behaviors viewed as appropriate. To minimize this bias in the presented research 5 items assessing dispositional tendency to self-serving bias were added to OCBQ. Results of the participants who scored high on social desirability were excluded from further analysis (5 participants). Moreover, the recommendations suggested by Donaldson and Grant-Vallone (2002) were followed. Donaldson and Grant-Vallone (2002) indicate that selfreport bias is particularly likely in organizational behavior research because employees are afraid that their employer could gain access to their responses. However, it can be reduced when research is not conducted in the workplace (Donaldson & Grant-Vallone, 2002, p. 249). The presented research took place in buildings at University of Warsaw.

Participants

The participants in this study were employees (with at least one year tenure in their present organization) who boost their education in business studies at the Faculty of Management, University of Warsaw. The participants were postgraduate and master level students at extramural studies. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Participants were informed that individual responses would remain confidential. Paper-and-pencil questionnaires were distributed during classes. 536 surveys were completed. 32 surveys were excluded from further research due to missing values or insufficient work tenure of the participants. A large majority of respondents were female (75%), the age of participants ranged from 21 to 57 years, the tenure with their organization ranged from 1 year to 32 years, 21% of participants reported that they had a managerial position in the organization. The goal of this study was to examine the relationships between OC profiles, OCB and life satisfaction among employees boosting their education in business studies. The overrepresentation of women among employees with higher education is typical for the Polish population (Feliksiak, 2008). Women consist of more than 60% of those with higher education. Moreover, the percentage of women in the population of higher educated employees in Poland seems to grow systematically (Górniak, 2015).

Research results

Data was analyzed using SPSS 17.0. Results of descriptive analysis of three commitment types are in line with the findings of Bańka, Bazińska and Wołowska (2002). Results are listed in Table 6. PAF analysis was conducted to confirm the findings of study 2. 55% of variance was explained.

| Scale of organizational commitment | Minimum score | Maximum score | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective commitment | 6 | 30 | 16.77 | 5.50 |

| Normative commitment | 3 | 30 | 19.53 | 5.21 |

| Continuance commitment | 4 | 30 | 18.40 | 4.76 |

Findings concerning hypothesis 1

Prior to analysis three commitment variables were converted to standard (z) scores. In course of k-means cluster analysis 3 profile solutions were tested (8, 6 and 5 profiles). This non-hierarchical data analysis technique gathered individual cases into a pre-specified number of clusters based on the commitment scores, in a manner that maximized between cluster differences and minimized within-cluster variance. K-means cluster analysis was suggested as the best method to test Meyer and Herscovitch propositions (2001) by Somers (2009) and Wasti (2005). The tested number of clusters was selected due to two criteria:

Theoretical interpretability.Tested were these profile solutions (8, 6 and 5) which were supported in an existing literature (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001; Somers, 2009; Gellatly et al., 2006; Wasti, 2005; Sinclair et al., 2005; Meyer et al., 2012).

Cell-sizes. The number of observations in every cluster was large enough for generalizability.

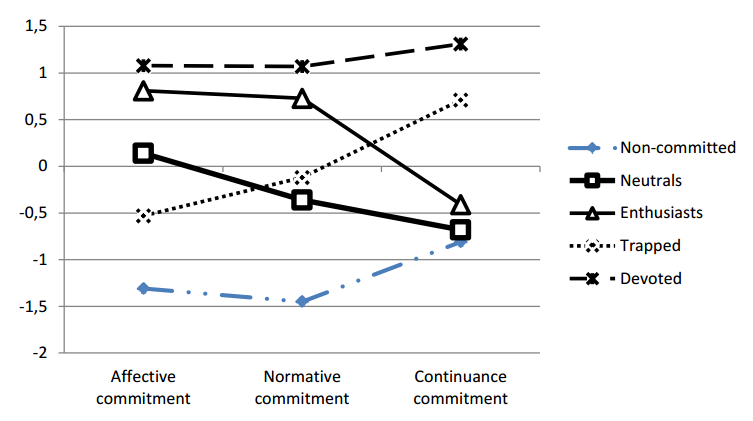

Finally, the 5-cluster solution was selected for further analysis. This solution was also the most appropriate in terms of diversification of commitment levels. The obtained profiles were consistent with theoretical and empirical premises. The 5-cluster solution appears in Fig. 2, which displays the means of each commitment type in every profile.

The first profile (Non-committed, n= 80) consisted of individuals at least one standard deviation below the sample average on AC and NC and 0.8 of standard deviation below the average on CC. The second group, labeled Neutrals (n=115), was characterized by slightly below average levels of all forms of commitment. Another group (Enthusiasts) consisted of individuals with high levels of affective and normative commitment (more than 0.5 of standard deviation above average) and below average levels of continuance commitment. The fourth profile was labeled Trapped because it consisted of individuals with high levels of CC, low levels of AC and average levels of NC. These individuals could experience a sense of being locked in a place they do not like and do not identify with but remain to avoid the perceived costs of leaving. The last profile group, named Devoted, consisted of individuals who displayed very high levels of all types of commitment (more than one standard deviation above the sample average).

According to the hypothesis 1, the findings supported the existence of 5 profile groups of organizational commitment. The obtained profile groups are in line with Wasti’s findings (2005)

| Profile groups | Noncommitted (1) | Neutrals (2) | Enthusiasts (3) | Trapped (4) | Devoted (5) | Post-hoc comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | 80 | 115 | 110 | 113 | 83 | |

| Life satisfaction | 13.1 | 14.7 | 15.6 | 13.2 | 14.4 | 2, 3 < 4, 1(b) |

| OCB | 90.6 | 101.2 | 112.9 | 91.4 | 110.9 | 2 > 4, 1 (a) 3, 5 > 2 (a) |

| Gender (% male) | 28.8 | 15.7% | 23.6% | 26.5% | 32.5% | 5 > 2 (c) |

| Note: The numbers in parentheses in column heads refer to numbers used for illustrating significant differences in the last column titled „post-hoc comparisons”; p < 0.001, p < 0.05, p= 0.052. | ||||||

Outcomes of commitment profiles – hypotheses: 2, 3, 4

To determine whether the obtained commitment profiles differ in respect to outcome variables, univariate analysis of variance ANOVA was conducted. The results indicated that general OCB (F= 33.94, p < 0.001) and life satisfaction (F=7.8, p < 0.001) differed significantly among profile groups. The assessment of homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test) demonstrated that the variance in profile was not homogeneous according to gender (Levene’s test = 10.14, p < 0.001) and organizational position (Leven’s test =19.20, p < 0.001). Thus, the Welch test was used to assess the statistical significance of differences among profiles. The results suggested that there were significant differences among profiles in terms of organizational position (Welch’s test = 4.54, p= 0.002). Following post-hoc comparisons of means using Dunnett t3 test revealed subsequent significant differences (listed in Table 7).

According to hypothesis 2, individuals in the profile group with strong affective and strong normative commitment demonstrated the highest level of OCB. Consistent with expectations, both profiles with high normative and affective commitment differed significantly from other profile groups in terms of OCB. However, the findings with regard to OCB have not supported hypothesis 3. The profile group with strong continuance commitment in combination with weak affective and normative commitment (Trapped) was not associated with the lowest level of OCB. Although the level of OCB was significantly lower for Trapped than for Enthusiasts, Devoted and Neutrals, there was no significant difference between Trapped and Non-committed. Thus, the assumption that strong continuance commitment is responsible for low level of OCB (Wasti, 2005) was not supported.

Results pertaining to life satisfaction (hypothesis 4) revealed that individuals belonging to Non-committed and Trapped displayed the lowest level of life satisfaction, whereas Enthusiasts were characterized by the highest level of life satisfaction. Interestingly, Neutrals also demonstrated high level of life satisfaction and differed significantly from Trapped and Noncommitted. Thus, hypothesis 4 is partially supported. Enthusiasts, as expected, achieved the highest level of life satisfaction but there were no statistically significant difference between Enthusiasts and Neutrals. Moreover, the profile with high scores on all commitments (Devoted) has not demonstrated an equally high level of life satisfaction. Aforementioned findings support Meyer and Herscovitch’s (2001, Wasti, 2005) assertion that high continuance commitment attenuates the positive influence of affective and normative commitment. It is noteworthy, that findings regarding life satisfaction mirror those for OCB. It is consistent with results obtained by Meyer et al. (2012).

Limitations

Although this study makes some important contributions to the understanding of organizational commitment profiles and OCB, some limitations of the presented study should be acknowledged. It is possible that the findings here could be biased in some way. First, the generalizability of the research might be called into question. The sample (N=503) and the population differ with respect to gender and age. Thus, the findings are claimed to be reliable only with regard to the population of employees boosting their education in business studies (Feliksiak, 2008). Future studies that rely on larger, more diverse samples of employees would provide greater statistical power.

Moreover, self-report measures were used to assess all variables concerned in the research. This method can provide a common method bias (Donaldson & Grant-Vallone, 2002). Organizational commitment can be assessed only with self-report measures but there are other methods available for OCB. It would be desirable in future research to obtain OCB ratings from peers and supervisors. However, several scholars have called the use of supervisor ratings of OCB into question (Allen, Barnard, Rush & Russell, 2000). Furthermore, the lack of sufficient distinction between OCB types is to be indicated. The presented research has failed to support the multidimensional structure of OCBQ, however, it is consistent with some of the previous research (Organ et al., 2006). Thus, future research should address this issue in a more detailed manner.

General Discussion

The first aim of this study was to adapt and develop two measures of attitudes and behavior of high relevance to organizations: Organizational Commitment Questionnaire – Polish version and Organizational Citizenship Behavior Questionnaire. This aim was successfully completed. Both measuring tools are reliable, empirically valid, and can be used for scientific or organizational assessment purposes. However, the research has not supported the factor structure of OCBQ and the measure is suitable only for assessing the general level of OCB. The findings are in line with previous research (LePine, Erez & Johnson, 2002; Podsakoff et al., 2013) that shows a very high correlation among OCB types.

The second purpose of the presented research was to examine the propositions advanced by Meyer and Herscovitch (2001) concerning commitment profiles and their associations with other variables. These propositions regarded the existence of multiple profile groups among tested employees and differences of work-related behaviors associated with distinct profiles. This is the first research that combined commitment profiles with 7 types of OCB. In all the previous research (see e.g.: Somers, 2005; Wasti, 2006; Meyer et al., 2012) the assessment of OCB was limited to one or two types of these behaviors.

Five profiles groups have been identified in a sample of Polish employees boosting their education in business studies. In addition, differences among clusters referring to life satisfaction were assessed. The differences among profiles in terms of other variables have revealed an interesting pattern of relations. Individuals belonging to Non-committed and Trapped do not feel positive emotions towards their organizations. What is more, Trapped feel that despite their lack of positive feelings concerning the organization they cannot leave it due to the perceived costs of leaving. These two groups are characterized by low levels of life satisfaction. Moreover, they are not willing to engage in OCB. On the contrary, Enthusiasts are happier and more willing to exert discretionary effort on behalf of the organization. The combination of commitments in this group shows that these employees want to remain in the organization; they believe it is a right thing to do, but they are not forced to remain by the perceived costs of leaving.

The results are also to be interpreted in terms of organizational potential of innovativeness. Innovativeness reflects the tendency of a firm to engage in and support new ideas and creative processes which may result in new products, services and technological processes (Ozsahin & Sudak, 2015). OCB describes behavior that contributes to innovativeness (Turnipseed & Wilson, 2009). Several conclusions might be drawn from the research, considering that OCB are beneficial for organizations desiring innovations and they are positively related with organizational innovative climate (Turnipseed & Turnipseed, 2013). First of all, organizations should examine the commitment profiles of their employee. Knowledge of prevailing profiles should guide the implementation of adequate HRM practices, for similar results (in terms of OCB) can be achieved with different commitment profiles. The present findings support the benefits to organizations from having employees with a strong affective and normative commitment (Wasti, 2005; Somers, 2009; Meyer et al., 2012). However, even individuals with moderate affective and normative commitment displayed high OCB but only when combined with weak continuance commitment. Results also confirm that strong continuance commitment is not necessarily disadvantageous for organization providing that it is accompanied by high levels of affective and normative commitment (Wasti, 2005).

From a practical standpoint, the presented results might be useful for organizations wanting to foster optimal commitment profiles. According to present findings, it appears that assessing the prevalence of various profile groups can be arguably more beneficial to an organization than considering the levels of commitment types in isolation. In conclusion, the findings of this research provide some important implications. First, they enlarge the body of evidence for the importance of considering the combining influence of commitment types when examining the implications of particular components of commitment (Gellatly et al., 2006; Meyer et al., 2012). More specifically, the results suggest that profile-focused interventions could be more beneficial to an organization than general efforts to increase commitment.

Direction for further research

The research provides an insight into the pattern of commitments, OCB and well-being of Polish employees (of course with respect to the limitations of the sample). Two measures provided by the presented research could encourage researchers to conduct additional confirmatory research of employees concerning the nature of profiles and the associations with other outcomes. Conducting research in different contexts and geographical locations would allow the constructs reliability and validity to be confirmed (Meyer et al., 2002). The next stage of research should focus on comparisons between different cultures. Further research should combine the possible impact of different organizational and national cultures with OC profiles and OCB. The intensity of willingness to go beyond the call of duty at work seems to be indisputably related to cultural context. It can be assumed that employees in nations characterized by high collectivism should display more OCB than employees in more individualistic cultures. Viewing OCB and OC profiles through a cultural context framework would be especially beneficial for international companies because it would enable them to tailor HRM practices aimed at boosting OCB to the specifics of the location.

References

- Allen, T., Barnard, S., Rush, M., & Russell, J. (2000). Ratings of organizational citizenship behavior: does the source make a difference? Human Resource Management Review, 10(1), 97-114.

- Angle, H. L., & Perry, J. L. (1981). An empirical assessment of organizational commitment and organizational effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26(1), 1-14.

- Astakhnova, M. (2016). Explaining the effects of perceived person-supervisor fit and person- organization fit on organizational commitment in the U.S. and Japan. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 956-963.

- Axtell, C. M., Holman, D. J., Unsworth, K. L., Wall, T. D., & Waterson, P. E. (2000). Shopfloor innovation: facilitating the suggestion and implementation of ideas. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(3), 265–85.

- Bateman, T. S., & Organ, D. (1983). Job satisfaction and the good soldier: the relationship between affect and employee citizenship. The Academy of Management Journal, 26(4), 587-595.

- Bańka, A., Bazińska, R., & Wołowska, A. (2002). Polska wersja Meyera i Allen skali przywiązania do organizacji. Czasopismo Psychologiczne, 8(1), 65- 84.

- Beagley, T. M., & Czajka, J. M. (1993). Panel analyzing of the moderation effects of commitments of job satisfaction, intention to quit and health following the organizational change. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(3), 552-556.

- Bergeron, D. M. (2007). The potential paradox of organizational citizenship behavior. Good citizens at what cost? The Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1079-1096.

- Becker, H. S. (1960). Notes on the concept of commitment. The American Journal of Sociology, 66(8), 32-40. Bohner, G., & Wanke, M. (2004). Postawy i zmiana postaw. Gdańsk, Poland: GWP.

- Bolino, M. C., Turnley, W. H., Gilstrap, J. B., & Suazo, M. M. (2010). Citizenship under pressure: What’s a good soldier to do? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(6), 835–855.

- Bolino, M. C., Klotz, A. C., Turnley, W. H., & Harvey, J. (2013). Exploring the dark side of organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(4), 542-559.

- Borman, W. C., & Motowidlo, S. J. (1997). Task performance and contextual performance. The meaning for personnel selection research, Human Performance, 10(2), 71-83.

- Brown, R. (1996). Organizational commitment: clarifying the concept and simplifying the existing typology. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 49(3), 230-252.

- Ceylan, C. (2013). Commitment-based HR practices, different types of innovation activities and firm innovation performance. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(1), 208-226.

- Chen, Z. X., & Francesco, A. M. (2003). The relationship between the three components of commitment and employee performance in Chine. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62(3), 490-510.

- Chen, C., & Huang, J. (2009). Strategic human resource practices and innovation performance. The mediating role of knowledge management capacity. Journal of Business Research, 62(1), 104– 114.

- Chinen, K., & Enomoto, C. E. (2004). The impact of Quality Control Circles and education on an organizational commitment in northern Mexico assembly plants. International Journal of Management, 21(1), 51-57.

- Cohen, A. (2007). Commitment before and after: an evaluation and reconceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 17(3), 336-354.

- Czarnota- Bojarska, J. (2005). Zachowania obywatelskie w organizacji. Praca i Zabezpieczenie Społeczne, 8, 9-11.

- Devece, C., Palacios-Marques, D., & Alguacil, M. P. (2015). Organizational commitment and its effects on organizational citizenship behavior in high unemployment environment. Journal of Business Research, 69(5), 1857-1861.

- Donaldson, I., & Grant-Vallone, E. J. (2002). Understanding self-report bias in organizational behavior research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17(2), 245-260.

- Feliksiak, M. (2008). Raport CBOS: Zatrudnienie Polaków. Retrieved from http://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2008/K_034_08.PDF

- Gellatly, I. R., Meyer, J. P., & Luchak, A. A. (2006). Combined effects of the three commitment components on focal and discretionary behaviors. A test of Meyer and Herscovitch’s propositions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(2), 331-345.

- George, J. M., & Brief, A. M. (1992). Feeling good – doing good. A conceptual analysis of the mood at work - organizational spontaneity relationship. Psychological Bulletin, 112(2), 310-329.

- Górniak, J. (2015). Polski rynek pracy - wyzwania i kierunki działań 2010- 2015. Warsaw, Poland: Polska Agencja Rozwoju Przedsiębiorczości.

- Hackett, R. D., Bycio, P., & Hausdorf, P. A. (1994). Further assessment of Meyer and Allen three-component model of organizational commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(2), 15-23.

- Hornowska, E. (2001). Testy psychologiczne: Teoria i praktyka. Warsaw, Poland: Scholar.

- Jamal, M. (2011). Job stress, job performance and organizational commitment in a multinational company. An empirical study of two countries. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(20), 20-29.

- Jaros, S., Jermier, J., Koehler, J., & Sincich, T. (1993). Effects of continuance, affective, and moral commitment on the turnover process. An evaluation of eight structural equation models. The Academy of Management Journal, 36(5), 951–995.

- Jaros, S. J. (1997). An assessment of Meyer and Allen’s (1991) three-component model of organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 51(3), 319-337.

- Jaros, S. J. (2007). Meyer and Allen model of organizational commitment. Measurement issues. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 6(4), 7-25.

- Jaworska, A. (2008). Kwestionariusze Osobowości Eysencka: EPQ-R oraz EPQ-R w wersji skróconej. Warsaw, Poland: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego.

- Jiménez Jiménez, D., & Sanz-Valle, R. (2008). Could HRM support organizational Innovation? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(7), 1208– 1221.

- Lee, K. Y., & Kim, S. (2010). The effects of commitment-based human resource management on organizational citizenship behaviors. The mediating role of the psychological contract. World Journal of Management, 2(1), 130- 147.

- LePine, J. A., Erez, A., & Johnson, D. E. (2002). The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: A critical review and metaanalysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 52-65.

- Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1979). Społeczna psychologia organizacji. Warsaw, Poland: PWN.

- Mayer, R. C., & Shoorman, F. D. (1992). Predicting participation and production outcomes through a two-dimensional model of organizational commitment. Academy of Management Journal, 35(3), 671-684.

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization on organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61-89.

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research and application. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Meyer, J. P., & Herscovitch, L. (2001). Commitment in the workplace. Toward a general model. Human Resources Management Review, 11(2), 291-326.

- Meyer, J. P., Stanley, L. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. A metaanalysis of antecedents, correlates and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20-52.

- Meyer, J. P., Becker, T. E., & Vanderberghe, C. (2004). Employee motivation: a conceptual analysis and integrative model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 991-1007.

- Meyer, J. P., Stanley, L. J., & Parafyonova, N. M. (2012). Employee commitment in context. The nature and implications of commitment profiles. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 1-16.

- Morrison, E. W. (1994). Role definitions and organizational citizenship behavior: the importance of the employees’ perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 37(6), 1543-1567.

- Mowday, R. T., Steers, R. M., & Porter, L. W. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14(2), 224- 247.

- Organ, D., Podsakoff, P. M., & Mac Kenzie, S. B. (2006). Organizational citizenship behavior: its nature, antecedents and consequences. California CA: Sage Publications.

- O’Reilly, C., Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment. The effects of compliance, identification and internalization on prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 492-499.

- Ostroff, C. (1992). The relationship between satisfaction, attitudes and performance: an organizational level analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(6), 963-974.

- Ozsahin, M., & Sudak, M. K. (2015). The mediating role of leadership styles on the organizational citizenship behavior and innovativeness relationship. Journal of Business, Economy and Finance, 4(3), 443-451.

- Penley, L. F., & Gould, S. (1988). Etzioni’s model of organizational involvement. A perspective for understanding commitment to organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 9(1), 43-59.

- Pffeffer, J. (1994). Competitive advantage through people. Boston MA: Harvard Business School.

- Podsakoff, P. M., Mac Kenzie, S. B., Paine, J. B., & Bachrach, D. G. (2000). Organizational citizenship behaviors a critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Management, 26(3), 513-563.

- Podsakoff, N. P., Podsakoff, P. M., Mac Kenzie, S. B., Maynes, T. D., & Spoelma, T. M. (2013). Consequences of unit-level organizational citizenship behaviors. A review and recommendations for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(3), 87-119.

- Porter, L., Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., & Boulian, P. V. (1974). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover among psychiatric technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59(5), 603-609.

- Rodriguez, M., Ricart, J. E., & Sanchez, P. (2002). Sustainable development and the sustainability of competitive advantage: a dynamic view of the firm. Creativity and Innovation Management, 11, 135–46.

- Shipton, H., West, M. A., Dawson, J., Birdi, K., & Patterson, M. (2006). HRM as a predictor of innovation. Human Resource Management Journal, 16(1), 3– 27.

- Sinclair, R. R., Tucker, J. S., Cullen, J. C., & Wright, C. (2005). Performance differences among four organizational commitment profiles. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1280-1289.

- Smith, C. A., Near, J. W., & Organ, D. (1983). Organizational citizenship behavior its nature and antecedents. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(4), 653-663.

- Somers, M. J. (2009). The combined influence of affective, continuance and normative commitment profiles on employee withdrawal. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(1), 75-81.

- Spik, A. (2014). Zaangażowanie organizacyjne pracowników oraz ich zachowania obywatelskie w organizacji (Doctoral dissertation). University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland.

- Turnipseed, D. L., & Wilson, G. L. (2009). From discretionary to required: the migration of organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 15(3), 201–216.

- Turnipseed, P. H., & Turnipseed, D. L. (2013). Testing the proposed linkage between organizational citizenship behavior and an innovative organizational climate. Creativity and Innovation Management, 22(2), 209-216.

- Takeuchi, R., Bolino, M. C., & Lin, C.-C. (2015). Too many motives? The effects of multiple motives on organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1239-1248.

- Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship behavior and inrole behaviors. Journal of Management, 17(3), 601-623.

- Wasti, A. (2005). Commitment profiles: Combinations of organizational commitment forms and job outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 290-308.

- Van Dyne, L., & Le Pine, J. A (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: evidence of construct and predictive validity. The Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 108- 119.

Biographical note

Aleksandra Spik, PhD, is a lecturer at University of Warsaw, Faculty of Management. She graduated from the Management Faculty and from the Psychology Faculty of University of Warsaw. In her scientific interests she focuses on organizational psychology and measurement of organizational behaviors and attitudes.